Contents

Guide

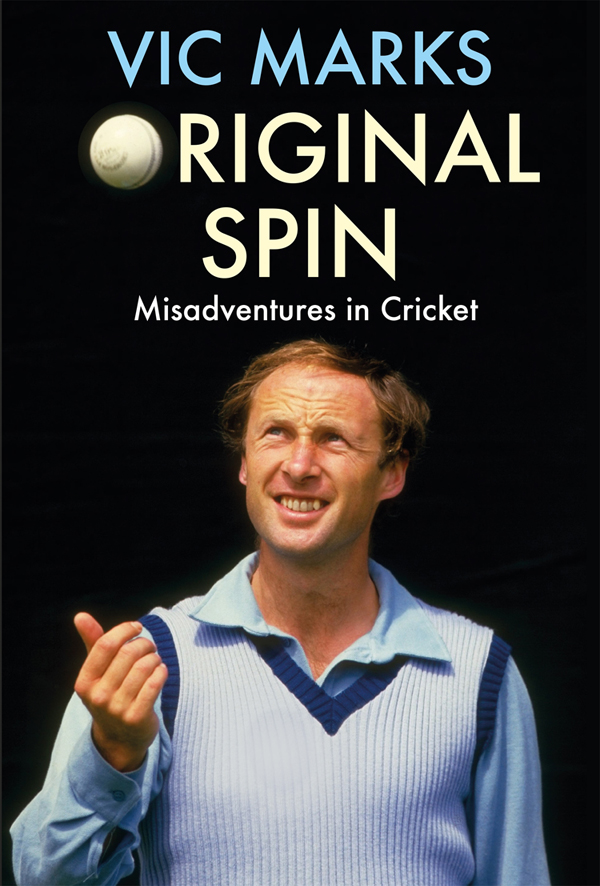

ORIGINAL SPIN

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Allen & Unwin

Copyright Vic Marks, 2019

The moral right of Vic Marks to be identified as the author

of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The

publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any

mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

All images in the photo inserts, unless otherwise credited,

are the property of the author.

Allen & Unwin

c/o Atlantic Books

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Phone: 020 7269 1610

Fax: 020 7430 0916

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library.

Internal design by Patty Rennie

Hardback ISBN 978 1 91163 019 7

E-Book ISBN 978 1 76087 197 0

For the Crackington Crew

CONTENTS

ONE

__________________

TAUNTON 1974

WELL, WERE NOT GOING to get into the team ahead of him. Peter Roebuck and I stared at one another and simultaneously came to the same conclusion.

It was April 1974 at the County Ground and the Somerset players were having their first middle practice. A gangling pace bowler from Burnham-on-Sea, Bob Clapp, who would one day become a far better teacher, raced in and hurled the ball down as fast as he could. The delivery was not too bad, a fraction short perhaps and a little wide. There was the crack of willow on leather and the ball disappeared to the cover point boundary at staggering speed. A square cut of awesome power and certainty. Clapp looked a little puzzled and crestfallen. Meanwhile the batsman made ready for the second delivery of his practice session, although it took some time for the first one to be retrieved from beyond the greyhound track that encircled the playing area. Isaac Vivian Alexander Richards had arrived in Taunton.

Richards was barely known outside Antigua and Lansdown in Bath, where he had played a season of club cricket in 1973. That state of affairs would not last for long. Those who had played with or against Richards at Lansdown had soon recognized something special. Within a decade it was tricky to argue with the assertion that here was the best batsman of his era. I never bothered to try. He was the best.

Maybe it was Richards exploits for Lansdown the previous summer that allowed him to change in the main dressing room of the old pavilion when he first reported as a Somerset cricketer in that spring of 1974. There he found himself alongside three giants of the county game: Brian Close, an exile from Yorkshire having been controversially sacked in 1970, was the captain of the club; Tom Cartwright, once of Warwickshire and an exquisite bowling machine, was now Somersets player/coach; and in his last season as a professional there was Gentleman Jim Parks, who had spent most of his career caressing the ball up and down the slope at Hove.

There were also some old Somerset stalwarts sitting under their usual pegs in that homely dressing room (well, there were a couple of sofas and an old gas fire in between the cricket bags) in the bucolic figures of Mervyn Kitchen and Graham Burgess, and some young ones, too namely a pair of athletic blonds from Weston-Super-Mare, Brian Rose and Peter Denning. To augment the locals there was an assortment of cricketers from elsewhere: within the last few years Derek Taylor, the wicketkeeper, had come from Surrey; fast bowler Hallam Moseley from Barbados; left-arm spinner Dennis Breakwell from Northampton; and from Sussex Allan Jones, who would end up bowling fast for a good percentage of the clubs on the county circuit before sending batsmen on their way with his right index finger as an umpire.

At the back of the pavilion was a little alleyway beyond which was a dingy stone-floored room, which in later years would serve far more appropriately as modest toilets for gentlemen spectators. There was one tiny, thin window near the ceiling, a couple of benches and a few pegs on the wall. This was where the new recruits to Somerset were housed since there was not enough room in the main dressing room for the entire staff. That room no longer exists; it was demolished to make way for the suave, state-of-the-art Somerset Pavilion in 2015. There were no preservation orders to overcome in that process.

Back in the winter of 1973 the chairman of cricket, Roy Kerslake, who had captained Somerset in 1968, had successfully advocated a youth policy to the committee. Hence there were five newcomers in addition to Richards: Phil Slocombe, another batsman from Weston-Super-Mare; John Hook, a tall, gentle, prematurely deaf off-spinner, who was also from Weston; Roebuck and Marks, who had both been enlisted as batsmen (Ill explain later) and a young man from Yeovil named Ian Botham. We were the occupants of the makeshift dressing room. All of us were eighteen years old though Botham seemed to have lived a bit longer or at least more vigorously than the rest. He tended to dominate proceedings even then, especially in our claustrophobic dressing room.

In that cubby hole a pattern emerged in those first few weeks. Ian rubbed along happily with Peter Roebuck, who was a very bright, Cambridge University-bound Dylan fan with huge feet, far more prepared to lower the drawbridge as a teenager than in later life. Ian and I were two South Somerset boys I had grown up on a farm near Yeovil and we got on perfectly well. Fairly early on in our relationship I learnt the necessity of identifying some form of escape route late in the evening when in Ians company. In Somerset I did not have to use it very often since I always had a forty-minute drive back home; hence the nocturnal haunts available in Taunton were never my specialist subject. By and large it always seemed wiser to avoid a serious argument with the young Botham if at all possible, a philosophy I maintained in later life.

Ian did not take so easily to Phil Slocombe; he sensed too many airs and graces, real or imagined. The point to remember, given how Somerset would disintegrate a dozen years later, was that Roebuck and Botham were once in the same camp, both intrigued by their obvious differences and enjoying one anothers company for the best part of a decade. They would argue merrily about most things and they would even write a book together, It Sort of Clicks, a task that, unsurprisingly, fell largely no, entirely upon the shoulders of Roebuck.

Slocombe, Roebuck and I had all come to the fore as cricketers by excelling to various degrees at local independent schools. Phil and Pete had played together, not necessarily in perfect harmony, at Millfield while I had been at Blundells School in Tiverton just across the border in Devon. Along the way we had all played cricket for the county in the school holidays sometimes in youth sides run chaotically by the old Somerset cricketer Bill Andrews, who, according to the title of his autobiography, possessed the hand that bowled Bradman (for 202) and later for the second team. That has been a pattern repeated frequently with the Somerset sides of the twenty-first century (minus the endearing, larger-than-life Andrews). Whatever the merits of the system, James Hildreth, Arul Suppiah, Jos Buttler, Craig Kieswetter, the Overton twins, Tom Abell, Dom Bess, Eddie Byrom, George Bartlett and Tom Banton have all progressed in a similar manner, though, as Jack Leach has demonstrated, other routes are still possible.