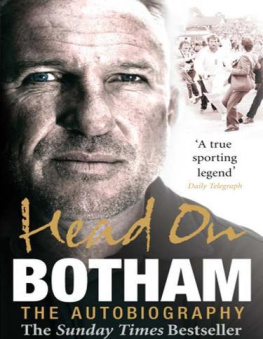

IAN

BOTHAM

First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2011

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright 2011 by Simon Wilde

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of Simon Wilde to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Grays Inn Road

London

WC1X 8HB

www.simonandschuster.co.uk

Simon & Schuster Australia

Sydney

A CIP catalogue for this book is available

from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-84737-648-0

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85720-446-2

Typeset by M Rules

Printed in the UK by CPI Mackays, Chatham ME5 8TD

For Freddie, Lily and Eve

Contents

Those who have been once intoxicated with power, and have derived any kind of emolument from it, even though for but one year, can never willingly abandon it.

EDMUND BURKE, LETTER TO A MEMBER

OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY, 1791

Introduction

A very particular type of sports star rose to prominence during what might be termed the first great age of televised sport from the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s. That there was a mass unseen audience out there somewhere in the ether seemed to affect the way these sportsmen conducted themselves, and how they viewed themselves. They became public performers in a way sportsmen had not been before. The mere presence of cameras enhanced the stature of all sportsmen regardless of how they performed, but the very best acquired a greater aura, wielded greater power, and ultimately accumulated greater wealth. With the help of television they could achieve heroic status even in a contest attended by only a few thousand, even a few hundred, people. This is of course precisely what happened with the Headingley Test match of 1981, the defining event of Ian Bothams career.

Not all sportsmen were comfortable with this shift. Some who thought little of playing in front of large crowds felt intimidated by televisions faceless but all-seeing eye. For a special few, though, a heightened sense of theatre was all they could have wished for. Television guaranteed them an audience of unquantifiable magnitude and, on the basis that recordings might be repeated any number of times, it literally offered immortality provided you were good enough to produce something worth watching again and again.

Muhammad Ali exemplified this hunger for fame through a lens but Botham fell into this category too. He saw himself as an entertainer, not only emptying bars in the grounds but filling sitting-rooms in homes, and he did so through the verve, courage and lion-hearted endeavour he brought to his play. He loved a big stage and there was none bigger than the Ashes. He displayed skill, especially with his bowling, but it was the unbridled physical commitment that stood out: he seemed to bowl forever, without ever getting tired. The cameras sometimes caught him changing boots and afforded a glimpse of battered feet and bloodied toes, a sight to turn your stomach. He was one of the bravest cricketers there has ever been.

I was among those out there in the ether, who first experienced Bothams heroics on TV. In his early years with England, his talent, exuberance and eagerness for battle leaped out of the screen. How could he be so at ease when most found it so difficult? Did he not suffer from nerves, or doubt? He was obviously personable, too; he shared in his team-mates successes; with greater regularity, they shared in his. Most strikingly, in an era when the default setting of most English cricketers was safety first, he was happy to take risks, and to accept that the risk-taking was not always going to pay off. This was the price of being an entertainer: he understood it, and we the public were asked to understand as well. He embraced being our champion and loved the power invested in him. It was too good to last. He was too good to last.

Even though I lived only a few miles from Headingley, I watched most of that great innings in 1981 on TV because I had, like most others, given up on England after watching them in person being outplayed for three days. Then, when he and Graham Dilley began their mayhem, I was stuck: dare I risk the 25-minute journey down to the ground or should I stay put and be sure not to miss anything? I stayed put, or rather transfixed, scarcely believing what I was seeing. I made sure I was at the ground the next day, and saw Bob Willis wreak havoc. I wanted to be a follower of the team from that day on.

The costs of being a peoples champion were to run deeper, very deep. By making such a conscious decision in the mid-1980s to wear striped blazers and strange hats, and long hair and droopy moustaches, Botham showed that he regarded the limelight as being almost as important as winning. And, because relying on his instincts had carried him so far, he believed that trusting his talent and not stifling his urges as some would have had him do was always the right thing to do. He worked less hard on his game and still did not agonise over failures. What was important was remaining true to the gifts for which the public loved him.

The real trouble started for Botham as it did for all the top stars when he stopped being so outrageously successful. People who felt they knew him from having seen him on TV were not so friendly when they met him in a pub with a few beers inside them. And administrators bewildered at the power he wielded were not always minded to cut him the slack he wanted when his instincts took him into dangerous territory off the field. The innocence evaporated and was replaced by a mistrust of the outside world the big out there that he thought he had tamed that at times slid towards paranoia. This prompted some reckless behaviour, as though he had reckoned that if others were set on destroying him, he might as well destroy himself first.

I also witnessed this second phase of his career, still mainly on TV though also quite often at closer quarters. Botham did not now seem such a pleasant man, or such a joyous one. There was an edge to him that had not been present during his youth.

He had been hurt by the world and seemed inclined to inflict hurt in return. There was more political calculation in what he did, more hunger for power and influence, and more preening. He was less open to compromise, or reason, and more defensive. There was often only one way to do something: his way. There were still brilliant performances, but increasingly they were outnumbered by bad ones. These years were harsh, disquieting and sometimes lonely. He needed more reassurance than he let on.

grace. George Best before him, and Alex Higgins and Paul Gascoigne afterwards, had similar experiences. They too were gifted, glorious entertainers, who were champions of the people and scourges of the Establishment. They too came into the world with little, and called on the Devils work to fill the hours between matches. They too perceived the outside world to be turning against them. Their response was to drink to excess and behave so badly that the world could not but fall out of love with them.

There was a difference though. By the late 1980s, a common fear was held by many observers, including myself, that, as Botham began to be sidelined by an England regime intent on restoring order and discipline, his career might fall off a cliff as spectacularly as Bests had and Higgins and Gascoignes would. But somehow it did not happen. They could not cope with fame, but he could. He teetered on the edge once or twice but pulled back. The pleasures of everyday life meant too much to someone who, while extraordinary in many ways, was down-to-earth and normal in others.