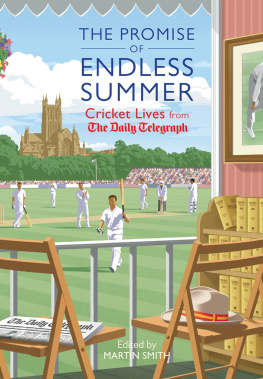

The Promise of Endless Summer

For my progeny, Alexander, William and Poppy, all hard-working students at universities around the country

It is not often that the death of a cricketer puts a temporary brake on affairs of state. However, the departure of the player who perhaps epitomised best the Britain of long shadows on county grounds [and] warm beer, brought a brief interlude in frenetic canvassing during the 1997 General Election campaign for the Leader of the Conservative Party. Just eight days before polling was due to begin, the Right Honourable John Major, M.P., took time out to compose for the Daily Telegraph a tribute to his boyhood hero Denis Compton, whose death had just been announced. To put it in its historical context, the incumbent prime minister was fighting for his future amid a frenzied atmosphere of political infighting, particularly over Europe, sleaze allegations against party members and an increasingly centralist Labour Party intent on taking advantage. Yet Major sheltered, metaphorically at least, beneath the hustings to write a heartfelt piece which appeared on the leader page of the following days newspaper. In it he turned back the clock fifty years, just as he had done in his 1993 speech about Britishness and warm beer, only this time to evoke fond memories of a golden age for cricket. Denis personified the romance of cricket, Major wrote. He was a hero to most males now over the age of forty-five, and his dashing batting and good looks had an appeal to the ladies, too, he continued. Throughout my boyhood he put to the sword often nearly single-handedly the best talent from South Africa, Australia and the West Indies. He concluded: He was an Olympian of cricket. Thank you, Denis. You left memories for all time, even for those who only saw you from afar.

In a few hundred well-chosen words, Major captured the appeal not only of D.C.S. Compton but also the appeal of cricket itself. It is a sport bound up in nostalgia and wistfulness for the black-and-white days when our heroes took off their demob suits and donned pristine flannels to face the best the Empire could throw at us. Cricket in the immediate post-War years continues to be viewed through a golden filter, helped no doubt by the long, hot summer of 1947 and the arrival of Don Bradmans impossibly glamorous, and apparently invincible, Australians the following year. The public were weary after six years of war and the cricketers put on a show that not only quickened the pulse but also underlined a joie de vivre that was palpable. Many of the players had seen active service during the Second World War and it may be no coincidence that the games most colourful characters Compton, Edrich and Miller were among them. The overwhelming feeling was one of relief just to have survived the conflict, and they put their backs and shoulders into expressing that relief. Compton had served with the Army in India; Bill Edrich rose to become a Squadron Leader in Bomber Command, and was rewarded with the Distinguished Flying Cross; Keith Miller flew Mosquitos over Germany with Messerschmitts hanging on to his tail (though he put it rather more robustly than that!) In 1947, Compton and Edrich compiled 7,355 runs between them for Middlesex and England, Compton including eighteen centuries in his 3,816 aggregate. Miller, the golden boy of Australia, greatly enriched the Victory Test series in 1945 and the Ashes series of 1948. No wonder the short-trousered, future prime minister was smitten.

Stories of the feats and deeds of those demob-happy cricketers have been handed down over the years, some doubtlessly embellished but none the worse for that. It is the essence of cricket; it is what makes bearable the endless winter nights when deckchairs, picnic hampers and binoculars have long since been stowed away. In his appreciation of M.C. Cowdrey, the opening paragraph of which not only forms the preface to this book, but also provides its title, Michael Henderson talks about a memory, intangible yet always present, of the game as it was and as it can be, like some promise of endless summer. As cricket-lovers we have a tendency to look back through rose-tinted glasses to days when the sun always shone, the game was played by gentlemen and England were always 302 for two at tea. We conveniently forget the frequent rain stopped play signs, the bouncers and beamers of certain Test series and the fact that Australia once ran up 404 for the loss of three wickets in the fourth innings to win an Ashes match at Headingley. Miller contributed just a dozen runs to that innings, incidentally. Cricket can take you off in tangential directions at times. Heres proof: Millers wicket in that fourth Test in 1948 was taken by Kenneth Cranston, an amateur who set aside two post-War summers to play cricket. And to a reasonable standard, too: he captained both Lancashire and England before retiring, as planned, to the family dental business. He died in 2007 and his sporting curriculum vitae is included within these pages.

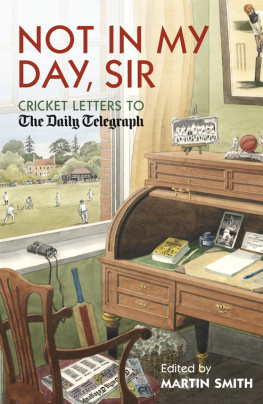

At this point it is probably worth establishing the parameters for what is ostensibly a celebration of cricketers past, particularly if you were hoping to read a eulogy to, say, W.G. Grace, C.B. Fry or J.B. Hobbs. They died in 1915, 1956 and 1963 respectively, and were naturally accorded fulsome, if slightly staid, death notices in the Telegraph. But until the mid-1980s, when Max Hastings became the papers editor, there had been no separate obituaries section as we know it today and reports of deaths took their chances amid the news selection of the day; consequently, they were generally much shorter, terser and gave little idea of the personality beyond the bare bones of their careers. Hastings appointed Hugh Massingberd to produce a daily obituaries page, and under him obituary writing was revolutionised. Though customarily unsigned, they became, as they still are, pieces of writing to rival any in the paper, full of colourful anecdote, mordant wit and trenchant judgments and, quite simply, an essential feature of the Telegraph.

Cricket could have been made for Massingberds new rubric, and indeed cricketers became a staple of his new order. While catching the big fish of the sport from the 1930s through to the 1960s, plus a few who played during the 1970s and later, the selection for this book has been mainly compiled from the Massingberd era. Some much longer pieces have been condensed for reasons of space, with the intention of bringing out the illuminating stories and insights that explain why the subject originally caught the imagination. These obituaries are complemented by a great many more pieces tributes, memoirs and elegies mostly published on the sports pages of the Daily and the Sunday Telegraph, from those who knew the subject well and in many cases played with or against him.

The articles are compiled not in chronological order by date of death, or even alphabetically, but in a way that juxtaposes and dovetails with contemporary team-mates, opponents, matches and events. The book begins with W.F. Deedess musings on his first sighting of Don Bradman in 1930, quickly followed by The Dons pre-War colleagues like Bill Ponsford and Bill OReilly, as well as opponents R.E.S. Wyatt, Harold Larwood and Bill Voce, before moving on to post-War contemporaries such as Ray Lindwall, Ron Hamence, Ernie Toshack, Len Hutton, Sam Loxton and Lindsay Hassett. John Majors favourite, Denis Compton, is surrounded by the similarly flamboyantly gifted Keith Miller and England and Middlesex sidekick Bill Edrich. Godfrey Evans is preceded by Les Ames in the wicketkeeping pantheon, and succeeded by his less demonstrative competitors for the England gloves, Keith Andrew and Arthur McIntyre, and international rivals Gil Langley of Australia and the Springbok John Waite. Members of the Surrey teams who won the county championship in seven successive seasons in the 1950s are grouped together (the Bedser twins, Peter Loader, Tony Lock and the two captains, Stuart Surridge and Peter May); so, too, are the leading lights in Hampshires championship win of 1961 (strike bowlers Derek Shackleton and Butch White plus their inimitable captain, Colin Ingleby-Mackenzie). Colin Cowdrey is sandwiched between two more notable, spiritual cricketers in Dickie Dodds and David Sheppard, who was England captain and later Bishop of Liverpool. The Right Reverend Lord Sheppard of Liverpool also contributes a piece on Cowdrey, who, along with Compton, is one of only two players from the eighty-two included here to be accorded two entries; it probably helps that Compton has John Major and Michael Parkinson batting for him, and Cowdrey has Michael Henderson and the Bishop. Two of crickets great writers and broadcasters, John Arlott and E.W. Swanton, are remembered affectionately by Tony Lewis and Scyld Berry, themselves two particularly perceptive journalists from the