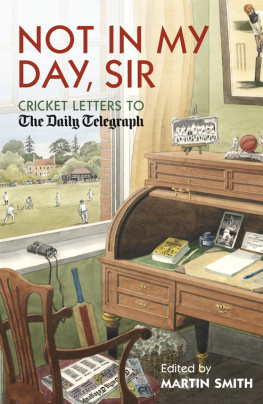

For my sons A.P.J. (bowler) and W.J.J. (batsman), in

anticipation of a long, hot, cricket-filled summer

CONTENTS

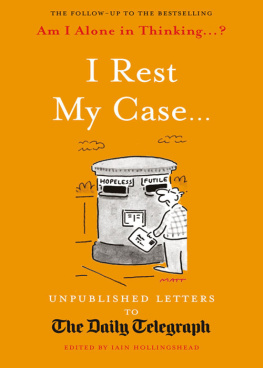

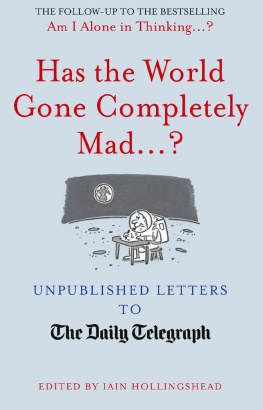

Field marshals, generals, major generals, brigadier generals, brigadiers, colonels, lieutenant colonels, majors, captains, sergeant majors, flight officers: enough top brass to start a fight, if not actually wage the war. Plenty of bluster, too, for this is not the batting order for an Armed Forces XI, but the first battalion of letter writers to The Daily Telegraph on the subject of cricket. They are backed up by a legion of reinforcements: the clergy are equally adept with pen and paper, canons to the right, reverends to the left; so too are many a good doctor, MPs, QCs, KTs, OBEs, MBEs, MCCs, and LBWs, not to mention the rank-and-file foot soldiers of the Barmy Army.

The stereotyping that depicts letter writers to the Telegraph, and particularly about cricket, as retired colonels from Tunbridge Wells contains more than a grain of truth. They thrive in London and the Home Counties. Over the years there must have been numerous egg-and-bacon-coloured MCC ties splattered with cornflakes after their wearers had choked over their breakfast on the words of E.W. Swanton, Michael Henderson or Simon Hughes.

There is a wonderful moment recalled in Huw Turbervills Telegraph Ashes history, The Toughest Tour, when the Duke of Norfolk wakes up one night in 1962 and announces: Id like to manage the tour to Australia, and his wife responds: Well, Marmaduke, you must tell the MCC. The image can be applied in a blink to a bewhiskered Major Major-type sitting in his MCC monogrammed pyjamas and harrumphing about unshaven players in sunglasses, Twenty20 whackit or the ban on taking alcohol into the members enclosure. To which his wife paraphrases the Duchess of Norfolk: Well, darling, you must write to the Telegraph.

And they do, they do. Thankfully they reach for fountain pens rather than double-barrelled shotguns to shoot down Messrs Swanton, Henderson or Hughes metaphorically rather than literally, with the battle cry: Have we got any stamps then, dear? Most days the Telegraph postbag contains a sizeable bundle of opinions, diatribes and forceful suggestions about something that has happened on or around one of the worlds cricket fields. The best of them may even be published. The very best of them may even appear here.

Anything and everything comes into their sights; a lot of the topics appear again and again like targets on a fairground stall, emphasising that there really is nothing new under the sun when it comes to cricket: the catering is still underwhelming at most grounds, the jobsworth on the gate still over-officious, the selectors always pick the wrong players, and the lbw law remains incomprehensible to all but the legislator who drafted it. And remember it is a law rather than a rule, as you will be constantly reminded if you transgress; this is cricket, after all, and rules definitely are not cricket.

If you put together all the theories and suggestions expressed by Telegraph readers the result would be a game that resembled a pushmi-pullyu even Dr Dolittle, let alone Dr Grace, would struggle to recognise. If one correspondent had his way, the pitch would look completely different, with the two sets of stumps not aligned: it would prevent bowlers following through, or batsmen running on the line of the stumps, and scuffling up the wicket, he reasoned. Another would have the teams batting alternately from each interval to end the bias of the toss, while in one-day cricket the teams would bat for half their overs, field, then bat and field again to help produce a level playing field. Or should that be an unscuffled wicket? And what is an unlevel playing field, anyway?

However, there would be no Frankensteins monster if a committee of Telegraph readers put together an identikit profile of their perfect player. Far from it. He would wear all-white, never spit, nor chew gum, wear a helmet or have hair longer than is permissible at Sandhurst; nor would he appeal speculatively or speak to the umpire unless spoken to, and he would always salute his superiors, especially if said superior was wearing an MCC tie. A bit of Army discipline never did anybody any harm, old boy.

You wonder how our forefathers got by before the Telegraph introduced a daily letters column in the early days of 1928. No doubt a lot of cats, or servants, were kicked before frustration and steaming rages could be channelled into something akin to coherent prose. The column was six or seven weeks old before the first cricket letters were published, and Mr J.A. Milnes proposal for an innovative points-scoring system in the county championship set the tone for the type of borderline-rational ideas that have peppered the pages ever since. (For information, it should be noted at this point that in those inter-War days the domestic fixture list was somewhat haphazard, and counties did not play each other as a matter of course, nor necessarily the strongest opposition, and this was a growing bone of contention.) Proposals for what was euphemistically called brighter cricket were part of the staple diet, and some were certainly colourful.

More than any other sport, cricket appeared with remarkable frequency in the midst of more weighty letter-writing subject matter such as war reparations, the annoying habits of delinquent telegram-deliverers on motorcycles, the rise of Fascism, the non-delivery of parcels from the Antipodes, and how you should handle horses on slippery surfaces.

At times cricket was elevated to such a matter of national importance that it led the letters section. Nowhere was that better illustrated than during the controversy over Bodyline (or Fast Leg Theory, if you prefer) during Englands 193233 tour to Australia, when a number of bouncers and beamers found their way into the letters column. The dOliveira and Packer affairs of 1968 and 197778 also raised hackles and the arguments of both sides make interesting reading. Slightly lesser squabbles, such as those centring on Ken Barringtons six-hour century for England against Pakistan, and that over the dirt in Michael Athertons pocket, also produced lively debate.

In between, there were regular comparisons with the past, great feats, great players, funny turns. Often the writers would drift into an easy-going set of reminiscences, putting each other right, about, say, E.M. Grace, C.B. Fry or Sir Donald Bradman; whether the correct terminology is the wicket or the pitch; and the conundrum of why it is that wickets are pitched to start the days play but stumps are drawn to end it.

All the best letters columns allow themselves the luxury of witty one-liners and the Telegraph has not been slow to follow suit. Some of the best arrived after Englands whitewash on the 200607 tour to Australia, suggesting the open-topped bus ride that celebrated the long-awaited Ashes success in 2005 be replicated, so that England supporters could boo the disgraced players; failing that, they should be sent home on an open-topped aeroplane.

A personal favourite of the genre, probably because it conjures up images of soccer manager Bill Shankly marking his long-suffering wifes birthday by taking her to a reserve-team game, is from a lady writer: When I got married in 1955 my husband told me he was going to give me the greatest thrill a girl could have on her honeymoon; he took me to Lords.

Sometimes, though, trawling through mountains of back-copies with ink-encrusted fingers, searching for that nugget of epistolary gold, the excitement of discovery is replaced by a yawning void where an obvious debate should be raging. The lack of comment on Bradmans farewell flailing of the Poms in 1948 can be partly explained away by the shortage of newsprint in those post-War years; but surely the colonels in the shires spluttered with indignation at, say, the introduction of helmets in the Seventies, or when the participants in a one-day game were revealed to be bona fide cricketers rather than the cast from a production of Lloyd Webber and Rices

Next page