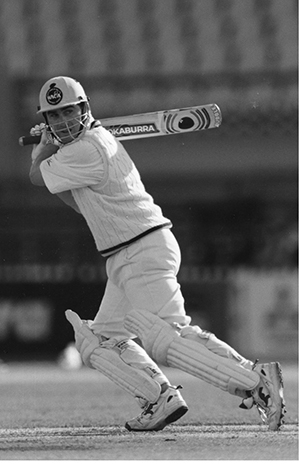

Consistent: Justin Alfie Langer shared 14 Test century stands and averaged 51 with Matthew Hayden, including back-to-back double centuries in their first two Tests together on Australian soil in 2001. Stephen Laffer

A

Theyve laughed, theyve cried, theyve shared, building an unbreakable bond

ACCIDENTAL PAIRING

If it wasnt for a brand new Mini Minor van with a stiff gearshift, Bill Lawrys celebrated pairing with Bobby Simpson at the head of the Australian order would have been delayed at least 15 months.

Australias senior opening batsman Colin McDonald developed such a sore wrist from changing the gears of a new car during the 1961 tour, he could barely hold a bat. Reserve opener Bobby Simpson had played each of the first three Tests down the list and was promoted to the top of the order with McDonald unavailable for both the fourth and fifth Tests. McDonald had bought the car for his wife Lois and young daughter Karen who, with the assistance of Ashes stalwart Alec Bedser, were renting an apartment in Nightingale Lane, Clapham.

The wives werent allowed to be in the same hotel as the players back then, said McDonald. Alec organised this apartment for us and, to help ferry Lois and Karen around, I bought this Mini Minor. I was lucky to get it as the demand for vehicles was far greater than the production, but it had this very stiff gear shift which I could only just move, so much so that I developed a repetitive strain in my left wrist, my top hand [which controls the bat]. By the end of the Leeds Test [the third of five, when McDonald made 54 and 1], I could hardly hold a bat and stood down from the last two Tests. I stayed on after the tour to work in the UK and never played another Test. I wish to goodness Id never got that car! But it was the start of the Simpson-Lawry union and my injury also saw Brian Booth come into the side for the first time. He was to become a very fine player for Australia.

The McDonald-Lawry stands in the first three Tests in 1961 had been worth just 27 per innings. Lawry and Simpson flourished from their first Test together at Old Trafford, sharing an important second innings stand of 113 before Richie Benaud famously went around the wicket and spun a revitalised Australia to the Ashes.

It was the first of nine century stands by the pair, including five against the old Enemy, their daredevil running between wickets an immediate characteristic.

It was something we always did. We both thought it safest at the other end! said Simpson. We didnt always call. Often it was just a nod. Wed drop the ball at our feet and off wed go. Its a lost art now.

The pair werent roomies, or particularly great mates. At night on tour, theyd generally dine separately. Yet Simpson felt more comfortable batting with Lawry than anyone else.

It was always a great comfort to see Bill at the other end, said Simpson. We knew each others games backwards and sometimes would look to take a particular end to help each other. I tended to play the spinners a little bit better than Bill. He was a great player of fast bowling and if one or the other was struggling just a little against a particular bowler, youd take the end where you could best help your mate.

Earlier in 1961, all in touring matches, Simpson had gone in first with Lawry five times for three century stands, including a double century partnership at Oxford. Few were as versatile in adapting from batting from No. 1 to No. 6. All but three of his first dozen Tests had been in the middle order. In his maiden series in South Africa, Simpson had gone in as low as No. 8 and in his first Ashes series the following Australian summer, hed played only one of the five Tests and had not been selected for the India and Pakistan tour of 195960.

In his bid to resurrect his career, Simpson shifted from New South Wales to Western Australia to open the innings regularly. While the internationals were away on the sub-continent, Simpson amassed 902 Sheffield Shield runs at the remarkable average of 300.66. In eight days he made two career-reviving double centuries, both not out. Of particular satisfaction was his 236 against his mates from New South Wales. He and veteran Ken Meuleman added 301 for the fifth wicket, Meuleman continually advising Simpson to cash in.

He kept saying to me, Dont throw it away. Keep going. When you get 200, think about 300. I didnt need much convincing, though, said Simpson. Only big scores were going to get me back into the Test side. I wasnt going to set limits on what I made. I just wanted to bat and the more runs I made the better.

During his monumental double against New South Wales, Simpson gloved a catch behind but survived the appeal. He was only in his 60s at the time. He always regarded it as the most timely reprieve of his career. Big runs against the power states, New South Wales and Victoria, always counted.

His first Tests opening the batting had been with McDonald at his side during the wonderful Calypso summer of 196061, his rapid-fire 92 in the deciding Test in Melbourne featured a rare thrashing of West Indian expressman Wes Hall, whose only five overs cost 40, including 18 off the first and nine off the second.

But it was alongside Lawry, the tall, angular, grafting Melburnian, where he was to make most impact.

So prolific had the unheralded Lawry been on arrival in the UK in 1961 that hed scored three centuries and averaged 80 leading into the first Test, his double of 104 and 84 not out against the MCC at Lords an Ashes selection clincher. It wasnt coincidental that his first two Ashes centuries, at Lords and Old Trafford, had seen the Australians win. By the end of his triumphant first tour, Lawry had been dubbed William the Conqueror.

Don Bradman and the Australian selection panel always favoured a left- and a right-hander at the head of the order and the Simpson-Lawry combine was a pivotal force in Australias top-order for five consecutive summers, home and away. Their judgment of the short single always seemed impeccable, ladies in the crowd often screaming as the pair stole ever-so-short singles, despite having just tapped the ball a yard or two in front of their feet.

Wed call, but not always, especially if we defended at our feet, said Lawry. We always reckoned the safest place to be was at the non-strikers end and wed do everything possible to get there.

Their highest stand and certainly their bravest came at Bridgetown in 1965 when they defied the fire of the two menacing West Indian expresses, Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith, to become the first Australians to bat through an entire days play on their way to a record stand of 382.

Griffith bowled five bouncers in six balls to Simpson and struck Lawry almost flush on the cheekbone with another short delivery, yards quicker than his normal ball. From his first delivery in the opening Test in Kingston, the Australians had labelled Griffith as a chucker.

No man can project a ball at 90 miles per hour from almost a standing start without throwing it, said Simpson.

The series had been billed as an unofficial world championship and in Hall and Griffith, the West Indies had the fieriest pair since Bodyliners Harold Larwood and Bill Voce. The West Indies won two of the first three Tests, Simpson and Lawry failing to share in even one 40-run partnership in their first five innings of the series. It was the first time theyd ever failed three Tests in a row.