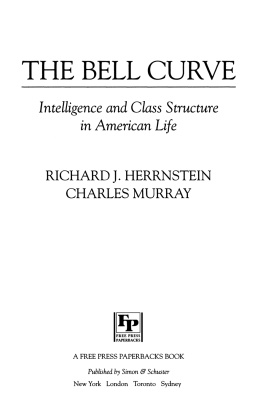

Straightening the Bell Curve

Also by Constance Hilliard

Does Israel Have a Future? The Case for a Post-Zionist State (2009)

Related Titles from Potomac Books

Father of the Tuskegee Airmen, John C. Robinson

Phillip Thomas Tucker

A Free Man of Color and His Hotel: Race, Reconstruction, and the Role of the Federal Government

Carol Gelderman

The Most Famous Woman in Baseball: Effa Manley and the Negro Leagues

Bob Luke

My Life and Battles

Jack Johnson; translated and edited by Christopher Rivers

Straightening the Bell Curve

How Stereotypes about Black Masculinity Drive Research on Race and Intelligence

Constance Hilliard

Foreword by COLIN GROVES

Copyright 2012 by Constance Hilliard

Published in the United States by Potomac Books, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hilliard, Constance B.

Straightening the bell curve : how stereotypes about black masculinity drive research on race and intelligence / Constance Hilliard ; foreword by Colin Groves. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61234-191-0 (hbk. edition)

ISBN 978-1-61234-192-7 (electronic edition)

1. Intellect. 2. Intelligence tests. 3. Race. 4. BlacksIntelligence levels. 5. MenIntelligence levels. 6. Stereotypes (Social psychology) 7. Discrimination in psychology.

I. Title.

BF432.N5H55 2012

155.82dc23

2012000623

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper that meets the American National Standards Institute Z39-48 Standard.

Potomac Books

22841 Quicksilver Drive

Dulles, Virginia 20166

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Stephen Hill

Contents

Foreword

There lives in Australia a man who has calculated the value of pi to more than twenty-two thousand decimal places in his head. He speaks seven languages fluently, and he has invented his own language with entirely consistent rules.

How brilliant is this man! How high his intelligence quotient (IQ) must be!

Actually, he is an autistic savant. He is unable to drive a car. He does not know his left hand from his right. The entire concept of IQ is meaningless; it tells us nothing of any importance about this man.

Allan Snyder, the director the Centre for the Minda joint project of the Australian National University and the University of Sydneyhas written a good deal about savants (including the man I have mentioned). Snyder has proposed the idea of a creativity quotient (CQ). Unlike devotees of the intelligence quotient (IQ), he does not look on this measure as an unalterably fixed number, but it seems to me to tell us at least as much about human minds as does IQ.

As Constance Hilliard recounts in this fascinating and revealing book, Lewis Terman largely developed the IQ concept in the first quarter of the twentieth century, and then Sir Cyril Burt promoted it extensively. But, by the very zealotry of their advocacy, both men helped bring the concept into disrepute.

I heard how Termans associate Catherine Cox had delved into the biographies of famous people of history and assigned two IQs to themone for childhood (up to seventeen years of age), one for adulthood. This process was to serve, in part, as a test of Termans hypothesis that IQ is pretty much a fixed quantity: the child is father to the man. I was fascinated and found Coxs monograph in the library. I was impressed with the amount of historical research but less than impressed with the amount of special pleading that she had indulged in, for example, when the juvenile and adult scores were far apart.

One of Coxs historical figures was Nicolaus Koppernigk, or Copernicus, as he called himself when he wrote in Latin. Cox assigned him a juvenile IQ of 105. I was not convinced. Here is one of perhaps two peopleCharles Darwin is the otherwho has done more than any other to put us in our place in the grand scheme of things. Copernicus overturned centuries of assumptions about the earth and the solar system with a single bold, remarkable insight. An IQ of 105! His adult IQ was much higher, but either Termans hypothesis about the child being father to the man is totally overthrown or else the whole schema was flawed from the start. Probably it was both.

Sir Cyril Burt was the man who, by himself or with two female associates (Miss Margaret Howard and Miss Jane Conway), studied pairs of identical twins who had been separated at birth and reared apart. He reported that the correlation between their IQs was 0.771; in other words, IQ depended largely on heredity, leaving little room for modification by education or upbringing. On the basis of his advocacy, the British government after World War II brought in a new system of secondary schooling in public education, requiring every child to take an IQ-based examination at age eleven or so (the Eleven Plus). Those children who passed went on to a grammar school (with the ultimate prospect of university entrance), while those who failed were relegated to a secondary modern school until they left at ages fifteen or sixteen, their futures marked out to be factory workers or cashiers.

When I was a PhD student at London University, I sometimes gave lectures on my field at grammar schools. Once, to my astonishment, I was asked to lecture at a secondary modern school. When I arrived, I talked first to the headmaster and learned a great deal. In brief, he and his staff had discovered that they were teaching many motivated, hardworking, andyes!intelligent students. There is something wrong here, they concluded, and they took pains to rectify the situation and ensure that the university option was open to any student who wanted it.

The Eleven Plus exam, as far as I know, has not involved this sort of grotesque injustice for some time now. The system did not work, but the real sting in the tail is that it seems to have been based on a fraud. Sir Cyril Burt could not possibly have studied fifty-three pairs of identical twins reared apart. His correlation coefficients could not possibly have remained exactly the same as his numbers of twin pairs increased. And he even appears to have invented his coresearchers, Miss Howard and Miss Conway. Controversy about Burts work still rages in British psychological circles, but no one doubts that Burt did not discover what he claimed to have discovered.

Given all these factorsBurts fraudulence, the soul-searching about cultural effects in IQ tests, all the discussion about different intelligences, the Flynn effect (the inexorable rise in IQ scores over the past fifty years or so), and the complexity of the entire subjecthow is it that claims are still made that some catch-all quantity of intellectual ability, either IQ or some other measure, differs between different social groups or, let us be open about this, between races?

Race is, as Hilliard shows, an iffy concept. It is undeniable that the human species varies geographically, but the differences are trivial, average not absolute, and recent. Races are not to be reified.

How is it then that some insist on combining these two iffy concepts, race and IQ, into one explosive mixture? It has often seemed to me that there is something obsessive about the way in which, oblivious of the problems, most proponents of race and IQ differences go about it. For example, finding one race scores lower on IQ tests than another, they state the difference is not bridgeable by education or social change; moreover, it is correlated with differences in other mental or physical characters, it is due to this or that evolutionary circumstance, and it has this or that consequence (separate schooling, residential separation, even athletic achievement).

Next page