Copyright 2001 by Marjorie Garber

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY

Reprinted with the permission of Simon & Schuster Books for

Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Childrens

Publishing Division, from Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll,

illustrated by Sir John Tenniell (Macmillan, NY , 1963)

The New Yorker Collection 2000 Roz Chast from cartoonbank.com.

All Rights Reserved.

Copyright, 1999, Danziger . Distributed by the

Los Angeles Times Syndicate. Reprinted with permission.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Garber, Marjorie B.

Academic Instincts / Marjorie Garber.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN: 978-1-40082-467-0

1. HumanitiesStudy and Teaching (Higher) 2. Literature

Study and teaching (Higher) 3. Universities and collegesCurricula.

4. Academic writing. 5. HumanitiesPhilosophy. 6. Learning

and scholarship. I. Title.

AZ182 .G37 2001

001.3'071'1dc21 00-056510

This book has been composed in New Baskerville Typeface

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements

of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper)

www.pup.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For my graduate students,

past and present

CONTENTS

PREFACE

IN COMBINING the most disciplined and the most undisciplined of forces, the title Academic Instincts is meant to sound like a contradiction in terms. But this is a book about the energies that keep scholarly disciplines from becoming inert and settled. It is about the instincts not of individuals but of fieldswhat might be called the disciplinary libido. In each chapter, I consider the ways in which a field differentiates itself from, but also desires to become, its nearest neighbor, whether at the edges of the academy (the professional wants to be an amateur and vice versa), among the disciplines (each one covets its neighbors insights), or within the disciplines (each one attempts to create a new language specific to its objects, but longs for a universal language understood by all). The chapters that follow thus address the current world of scholarship in the humanities in three different modes: through persons (The Amateur Professional and the Professional Amateur), institutions (Discipline Envy), and language (Terms of Art).

I suggest that various attacks against the academic profession and various feuds within itthe disparagement of amateurs by professionals and professionals by amateurs, the desire to keep the disciplines pure, the accusation that academic writing is, unlike the language of the real world, jargon-ridden and incomprehensibleneed to be reconceived. My fundamental argument has two strands. One is to show that these feuds are not stable. Amateur, for example, functions as a term of praise during one period or if it comes from one direction, and as a term of abuse during another or if it springs from a different source. What is taken to contaminate different disciplines varies as the prestige (and intellectual accomplishments) of other disciplines change. Terms that are jargon today will be everyday language tomorrow. The other strand of my argument is to show that many of the contrasts around which these disputes revolve do not signify real opposites, but rather depend upon one another for their strength and effectiveness. In each case, I will maintain that the terms of praise or abuse have a double nature, and that it is important to acknowledge that doubleness. The doubleness, in other words, is in many ways more important than the positive or negative judgments the terms convey at any one time. The point is not to choose the right inflection for each term but to show how intellectual life arises out of their changing relationship to each other.

I should say something here about what this book is not. It is not a developmental history of the disciplines or of the profession of teaching English or the humanities. That work has been powerfully and effectively undertaken by scholars like Gerald Graff, John Guillory andW. Bliss Carnochan. This book is not the story of the encounter of the humanities with the world of science and social science, the world of fact. That kind of work, too, has been well done, by Peter Galison and Mary Poovey among others. And this book is not the latest salvo in the so-called culture wars, a formulation that was always more hype or buzz than pedagogical reality. I address these questions not to take a side in the polemic, nor to position myself above it, but to explore the ways in which these controversies are essential to the nature of intellectual life. The things deplored or defended in discussions of the humanities cannot be either eliminated or endorsed, because the discussion itself is what gives humanistic thought its vitality.

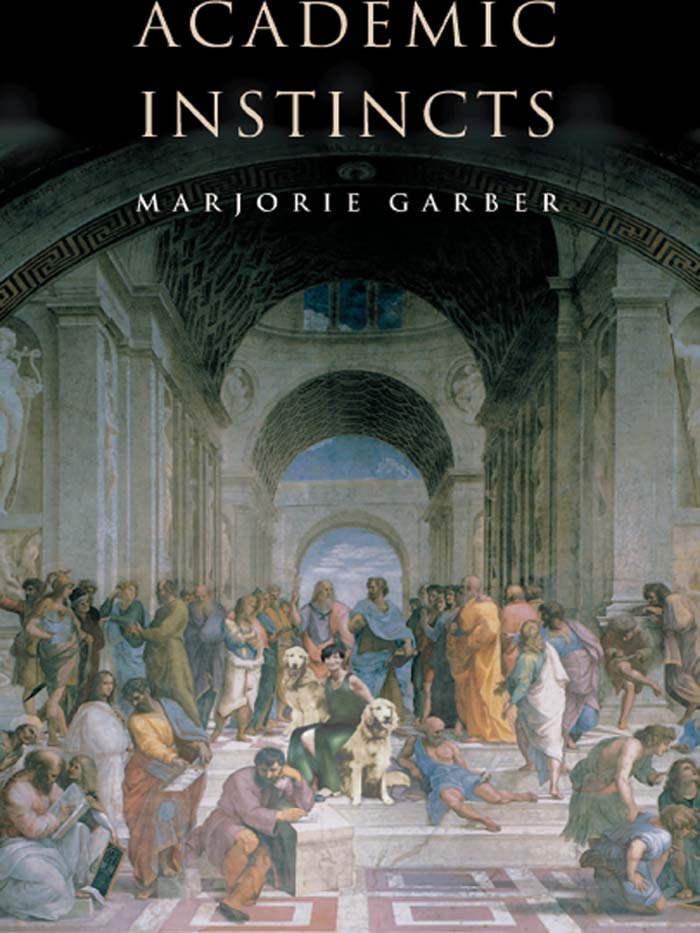

Scholars, despite what their critics say or what they themselves may claim, are basically conservative creatures (in the widest sense of that misused term), whose engagement with ideas and with students has been very much the same since the time of those renegade pedagogues, Plato and Aristotle. Despite the presence of Diogenes and of two delighted golden retrievers on the cover, there are no cynics in these pages, and relatively few, all things considered, in academic life. Teaching and writing at a college or university is a job for optimists and for idealists, whatever discursive or critical mode we may use in trying to shape ideas and the world.

So this book is not a history. It is an analysis, an intervention, and a credo. Although in the pages below I will make some pointed observations about the evocation of love in the teaching of the humanities, it would be fair to call this a love letter. A letter, sometimes critical, sometimes affectionate, alwaysI hopepassionate, addressed to a lifelong partner and companion, the profession of literary study.

THE AMATEUR PROFESSIONALANDTHE PROFESSIONAL AMATEUR

Criticism, is, I take it, the formal discourse

of an amateur. R. P. BLACKMUR

THE ELECTION of Jesse (The Body) Ventura, a former professional wrestler and radio talk-show host, as governor of Minnesota was described by the New York Times as an example of the lure of inspired amateurism. But of course American politicians have often tried to present themselves as amateurs, from George Washington to Ronald Reagan. Politics is a dirty business, and a professional politician an object of suspicion. Better to have a background in something, almost anything, else.

Like sports, for example. Former Senator Bill Bradley was a professional basketball player. Jack Kemp, a former housing secretary and candidate for vice president, was an NFL quarterback. Representative Steve Largent, the top draw for Republican fund-raisers in 1998, was a Hall of Fame wide receiver for the Seattle Seahawks. J. C. (Julius Caesar) Watts II was a college football star. Lets hear it for the athlete as president! said tennis player John McEnroe at a fund-raising rally in Madison Square Garden for candidate Bradley.

Or consider, at least in the state of California, politicians from the world of entertainment. Not only Ronald Reagan but Sonny Bono, Clint Eastwood, George Murphyand even, briefly, Warren Beatty. Or business. Think of the campaigns of Steve Forbes and Ross Perot, and even the trial balloon sent up by Donald Trumpall candidates who presented themselves as can-do men untainted by politics, bringing the power of their success in the marketplace to bear on national problems.