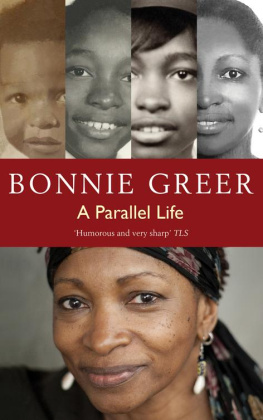

I was born in Chicago, city of the blues.

I grew up on the South Side, one of the blues seedbeds.

Im the eldest child of plain-speaking people who came from people who, like them, worked hard, often for less than they were worth, and many times for nothing at all.

They partied on Saturday night and went to church on Sunday.

They raised their children to live better and longer than they did and to die wealthier.

And always to be proper and to love the Lord.

They had no horizon other than the better and they stayed amongst their own. Even if they didnt want to do that all of the time, they had no choice, so it was best to make a virtue of it.

Education was basic and brief, but they aimed for more for their children, telling them to never forget mother wit.

They may not have completely approved of me, but would not have been surprised.

They were what the late poet Amiri Baraka called Blues People.

These Blues People took the big trains up from the cotton fields of the South to be with kin and start anew.

I come from a people who always moved, once they were freed from being a part of the land. From being the land.

The great blues singer Howlin Wolf said: Never forget your inherit.

And with these moving people, you always had to call them by what they called their right name, the name you call yourself. Not the name given to you by others.

And the names?

Coloured; Negro; black; Black; African American.

The words that have been used in my lifetime to describe me. Ive used most of them myself.

But these words never came close to describing me, nor that parallel life the one that sustains me, the one that propels me forwards. The one that has always directed me the other way, made me look on the other side.

It is sans foi ni loi lawless. It is touched by nothing and no one. Not even me.

It has its route, and sometimes makes itself known, leaving me with the task of deciphering its language, learning all over again its codes, its rules, its terrain.

Still.

But it merges more often now.

This parallel life holds my arboretum, my mythology, my landscape, my story. If I am lucky, it will be this parallel life that will be with me at the very end.

Words for me are rooted in music sound and images. I remember people and events and eras that way. Words exist in images, colours, sounds.

Take the word Negro.

That word always had a grey, metallic colour in my mind. The sound of it was like a scouring brush on an old frying pan: harsh, hollow, ugly.

Its music is one of those soppy, sentimental harmonicas that always accompanied Sidney Poitier when he used to die in the movies a lot.

Never liked it. Never used it.

Which was funny because as a child growing up in the late 1950s it seemed to be the name du jour, a name that made people actually happy or invoked serious discussion on TV; the name screaming from the covers of magazines in the shops in our neighbourhood (Negro Discovers the Secret of the Universe!) on the West Side of Chicago, Lawndale, the Badlands.

When Muhammed Ali asked once on TV: Negro? Where is Negroland? I jumped up and down with glee. Somebody had finally said it.

Of course, I learned later on that Negro/negro came from the Spanish. That was no excuse.

But it did give me something.

It was the word Negro that gave me one of the first signs of my synaesthesia, that gift/curse part of the socalled primitive brain, the in utero state that can cause an individual to see sound. A note can be seen as an object, for example, or a word can conjure up an entire film. Or a word like Negro was and is ugly in my minds eye.

I dont care for Black, nor African American nor BAME.

Theyre not as bad as Negro, but theyre like a flat desert.

African American looks like one of those hair ads from the 1970s with the man seated in a high-backed wicker chair, a palm tree draped over the top of it, and his lady leaning towards him in a tiger-skin, off-the-shoulder gown.

I prefer black to describe me.

Just plain black.

When I was a child, to call someone black was an insult, a curse word, something that made you fight.

But to me it contains all of the history of oppression and resistance, of being close to the soil and the sky, of plain speaking. Of The Journey.

In the 70s, I had to work my way through university, so one of my jobs was waitressing at a legendary blues club.

One night a big, tall, what folks would call a country black woman, dressed in farmers overalls and with a guitar, climbed up onstage. Everybody stopped what they were doing.

She surveyed the audience and said: Hello. Im Big Mamma Thornton. I wrote Hound Dog and this is the way you supposed to sing it.

She slowed it right down to the level of a menace to life. A truth-telling woman recounting a statement from another truth-telling woman to a man who messed up her life. Through her voice I saw a free woman, down on her land, a woman who knew how to kill her own chickens, hunt her own possum, cut her own cotton, fix her own roof, make her own whiskey, walk in her own shoes, and speak her mind, tell her own story.

A black woman.

Ready for the journey.

The Journey.

There is an irony in the American search for roots.

With the important exceptions of Americans descended from enslaved Africans, the peoples once called Indians, and those whose ancestors were part of the work cargo imported from China in the nineteenth century, enslaved in all but name, Hispanic Americans and indentured Europeans the majority of those who became Americans arrived more or less voluntarily, eager to forget their roots, or at least the unpleasant bits. This can make for startling discoveries.

I once met, in the South of France, an Italian American airline pilot named Sal. Sal had the profile of a Roman coin; he could be nothing but an Italian. He was perfect.

Sal sat in total amazement when, over several small glasses of spirit, my husband and I talked about Rome. And Renaissance Italy.

Suddenly he said, in a small voice: Did Italians do all that?

He then explained to me that his parents and grandparents told him nothing about Italy. Nothing. Theyd wanted to forget it. Forget the Old Country. They wanted to be new. They wanted to be Americans.

But the official erasure of any existence before enslavement as if black Americans did not exist before the yolk and the chains and the whip has always created a passion for us. Black people need to find out. We have to find out Who We Are. And Where We Come From.