Tales from a Masters Notebook

Stories Henry James Never Wrote

EDITED AND INTRODUCED BY

Philip Horne

WITH A FOREWORD BY

Michael Wood

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9781473545465

Version 1.0

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

VINTAGE

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

Vintage is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Compilation, introduction and The Troll copyright Philip Horne 2018

Foreword copyright Michael Wood 2018

Father X copyright Paul Theroux 2018

Silence copyright Colm Tibn 2010. First published in The Empty Family: Stories by Colm Tibn (Viking, 2010). Reproduced by permission of Penguin Books Ltd.

Is Anybody There? copyright Rose Tremain 2018

Canadians Cant Flirt copyright Jonathan Coe 2018

Old Friends copyright Tessa Hadley 2018

The Road to Gabon copyright Giles Foden 2018

Testaments copyright Lynne Truss 2018

Wensleydale copyright Amit Chaudhuri 2018

People Were So Funny copyright Susie Boyt 2018

The Poltroon Husband copyright Joseph ONeill 2018

Cover illustration Cassie Byrnes

The contributors have asserted their right to be identified as the authors of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This collection first published in Great Britain by Vintage Classics in 2018

penguin.co.uk/vintage

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

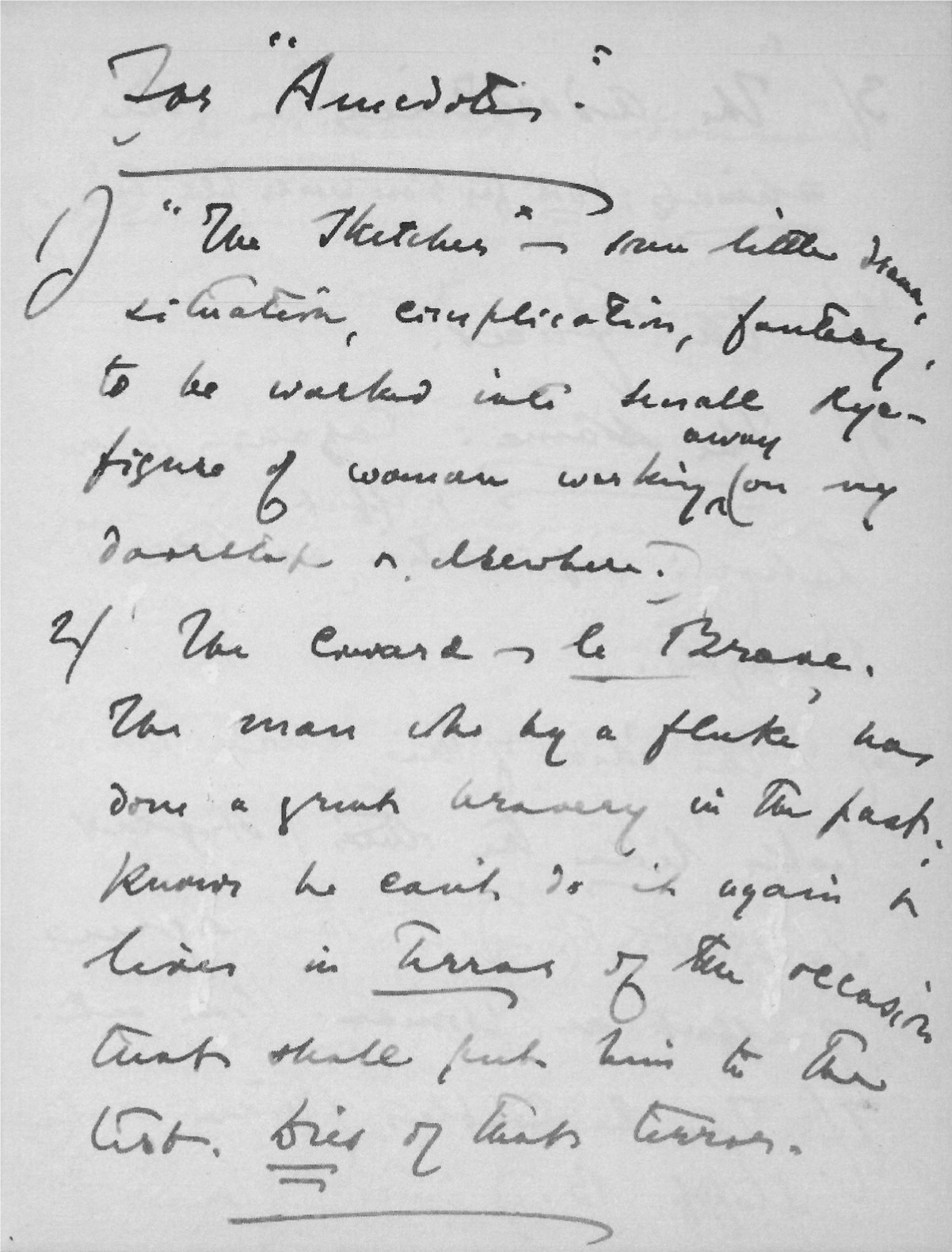

A page from Jamess Notebooks, from 1899, showing two of Jamess ideas, under the heading Anecdotes (as if that might have been the title of a collection), for stories that he didnt ever write. The first, The Sketches, no one has ever picked up; the second, The coward, is the basis of Giles Fodens The Road to Gabon. A transcription of the second can be found in the Appendix (see ); the first reads thus: 1) The Sketches some little drama, situation, complication, fantasy, to be worked into small Rye-figure of woman working away (on my doorstep & elsewhere.) (MS Am 1094 (2221a) vol. 6, Houghton Library, Harvard University)

FOREWORD

Henry Jamess Notebooks are full of what he liked to call little ideas, some of which he turned into long and famous novels. Many became short stories and novellas, others remained notes only, possibilities abandoned or not even picked up. The ideas took the form of what James thought of as, to quote words used in the appendix to this book, notions, subjects, incidents, fantasies, themes, situations. I have my head, thank God, full of visions, he said in 1895. One has never too many one has never enough. There is something alluring about this plenitude, especially when we think of the visions that were never seen again, and remember perhaps Jamess own marvellous description of the set-up for his story The Beast in the Jungle in August 1901: That was what might have happened, and what has happened is that it didnt.

Sometimes Jamess jottings take us quite a way into the resulting work, as with this prelude to The Turn of the Screw: Note here the ghost-story told me at Addington (evening of Thursday 10th) by the Archbishop of Canterbury. That tale begins with the mention of two ghost-stories being told at a country house and continues with the telling of a third the framing being crucial to the narrative. I mention the tale also because James was later rather dismissive of it in a way that is wonderfully instructive he thought he could manage something less grossly and merely apparitional and because this present volume, Tales from a Masters Notebook, is full of ghosts, if we think of them as matter that cannot die. I dont wish to suggest the eleven remarkable stories presented here are narrowly focused, or that James wrote only about the undead. James wrote about many things, and our contemporary writers are different from him and from each other in their tone, theme, setting and much more. But Jamess ambition for a more refined type of haunting, of a non-apparitional or not merely apparitional ghost, allows us to connect some very varied preoccupations.

Here, briefly described in the light of this thought, are instances you will find in this book of states between life and death: a memory that returns, with real difficulty, as a literal ghost, not seen but heard; a conversation that will never be reported; a secret enemy; a secret life; a test of courage that is also a test of worldliness; a dream of the past as a rich, untouchable fantasy; a waiting for what will live only as long as it is waited for, not consummated. There are also evocations of the clumsiness of failed misbehavior; of the double fear of being found out and of leaving no trace; of an attempted rescue of a life that may not have needed rescuing; of deep and shallow interpretations, perhaps both correct, of a dead mans collection of objects.

The settings of the stories range from Arizona to Norfolk, and from Calcutta to Gabon. The voices are witty, distant, knowing, baffled, confident, the literary strategies very varied. In no instance do we feel the contemporary writer has done what James might have done, so there is, as Philip Horne says, no element of pastiche or even of homage here. This is what the little word from means in the title. We are closest to what James himself thinks or a persuasive version of what James himself thinks in Colm Tibns story in this volume. James tells Lady Gregory that he often

noted down something interesting that had been said to him, and on occasion the germ of a story had come to him from a most unlikely source, and other times, of course, from a most obvious and welcome one. He liked to imagine his characters, he said, but he also liked that they might have lived already, to some small extent perhaps, before he painted a new background for them and created a new scenario.

This offers an image of what all the authors here are doing, with the emphasis on the repeated word new. The relation of idea to story is very subtle, and conceptually similar to that other kind of haunting James aspired to with his non-apparitional ghost. Real, historical people inhabit many of the anecdotes that are told to James. Although they have already lived, they do not become Jamess characters until he has found a new background and scenario for them. Only then do they become the people James likes to think may have already lived, with all the entangled possibilities of a fictional existence now lying in wait for them.

The life of all the stories in this volume begins, in a sense, with the first sentence of each. They have no past. Or more precisely they had no past until their authors chose one or were chosen by one and went on to do something with it. In that process each of these stories too seems to live, to occupy a world the author already knows, either through their experience or imagination. This feature connects them with Henry James not simply through lineage or debt but through a common practice of the art of fiction, a passion for which, as he said in