everybody who didnt.

And for my parents, who did the best they could.

When I was first shopping around the idea for this book, one editor gave me some well-intentioned advice. Youre only twenty-eight years old, she said. Youre too young to write a memoir. Needless to say, I didnt listen, and here we are.

Id first like to thank Denise Oswald, my wonderful editor at Dey Street, who had my back like a true soldier throughout this process. But I wouldnt ever have found myself in the same room as Denise were it not for my lovely literary agent, Lindsay Edgecombe of Levine Greenberg, who believed in my work and took a chance on a first-time author.

Thanks must also go out to every digital security expert I harassed while writing this book, especially Dan Guido of Trail of Bits and Eva Galperin of the Electronic Frontier Foundation. I appreciate your patience and willingness to humor me.

To my friend Josh Wood: thank you for your valuable notes, and for all the late-night Dominos.

Im indebted to every person who agreed to be interviewed for this book (regardless of whether they have come to regret that decision), but my special thanks go out to Terry Waite, Robert Fisk, Nick and Cass Ludington, Don Mell, Shazi Faramarzi, Gianni Picco, and Lou Boccardi, all of whom personally played various roles in the strange production that was my childhood.

To my half-sister Gabrielle: you forgave me for being the chosen one and became my friend, for which I will ever be grateful.

My gratitude also goes out to all the officials in the United States government and intelligence services who worked hard to help free my father and his fellow hostages. Regardless of the outcome, I know many of you had the best of intentions. Thank you for your service in support of my family.

Lastly, this book would not have a happy ending were it not for my fianc, Jeremy, and his beautiful little boy, Ari, who are helping me build the family Ive always wanted and never believed I deserved to have.

In a mad world, only the mad are sane.

AKIRA KUROSAWA

As far back as I can remember, maybe age three, I was aware of what was happening to my father. I didnt know exactly how dire the situation was, but I always knew, on some level, that he might be killed at any moment. Though my mother never came right out and said it, its hard to protect a child from something like that.

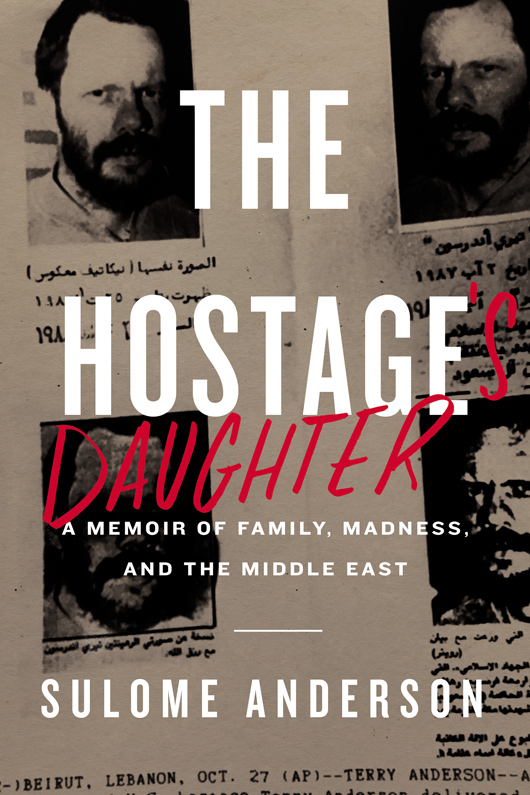

Here are the barest facts: In March 1985, my father, Terry Anderson, the Associated Press bureau chief for the Middle East at the time, was kidnapped in Beirut by a Shiite Muslim militant group known as the Islamic Jihad Organization. It was one of the militias that came to be associated by most with the Hezbollah movement, which has since become the single most powerful force in Lebanon. My mother was six months pregnant with me when he was taken. Dad was one of ninety-six foreigners kidnapped in Lebanon during the 1980s, ten of whom died, in an episode known as the Lebanese hostage crisis. He was released after almost seven years, and I met him for the first time.

But facts are cold, impersonal things, and you can find those in any book about the kidnappings. You can find them in the hundreds of archived news stories about my father and mother and me; in the TV appearances that wrapped up our happy ending like a chocolate, soon to be discarded uneaten.

This is not that sort of book. This is what happened when the cameras went away and we were left unobserved, blinking in the dark. Its the legacy of trauma I was born with and how it led me to ask questions about the event that shaped my life.

Im now a journalist working in Beirut, the city where it all startedjust as Dad was. This is my story, but its also the story of Lebanon, a place haunted by the phantoms of a bloody fifteen-year conflict, forever peering into the maw of another disaster. The tiny, politically exhausted country is currently sandwiched between war-ravaged Syria and Israel, its enemy and former occupier. As I write this in January 2016, Hezbollah, now the countrys dominant militia and political party, stretches itself thin. In Syria, the Iranian-backed Shia group joins president Bashar al-Assads brutal regime in battling rebel fighters and the terrorist caliphate calling itself the Islamic State. While spending itself in Assads war, Hezbollah never stops warily eyeing Lebanons southern border with Israel, preparing for an almost inevitable conflict with its longtime nemesis.

Meanwhile, sectarian Lebanese politicians are hopelessly deadlocked and unable to reach a consensus on electing a presidentthe country has been leaderless for more than a year and a half. The Lebanese parliament is so fractious it hasnt been able to agree on a company to dispose of Beiruts trash since last July. Stinking mounds of garbage decorate almost every main road in the city now. After watching it accumulate for months, the Lebanese have taken to burning the refuse. Across Beirut, plumes of reeking black smoke curl up to the sky. The once-lovely city is swaddled in a heavy smog you can almost taste, and when the roads flood with winter rain, they spread the filth with them. By some miracle, the country continues to sputter along, but it has become painfully obvious that the situation is unsustainable. As a friend recently put it, Lebanon now has the dubious honor of being the worlds most successful failed state.

In November 2015, the Islamic State carried out coordinated suicide attacks in a neighborhood I often visit, killing forty-four people. It was the most recent in a series of bombings targeting Shia areas of Beirut, where Hezbollah reigns supreme. But a few short months later, life in the city continues and the incident seems to have been largely forgotten by all except the relatives of the dead. The Lebanese have lived with the daily threat of terrorism for so long that it has become almost unremarkable to them.

Americans are less accustomed to these perilous circumstances. The Islamic Jihads spate of suicide bombings and kidnappings in Lebanon during the eighties was one of the first incarnations of modern-day terrorism against the United States. At the time my father was taken, these types of politically motivated attacks against Western civilians were unusual.

Nowadays, the threat of random political violence is part of our global reality. The day after the Beirut bombings in November, several Islamic State terrorists simultaneously attacked locations in Paris, including a caf and a concert hall. One hundred and thirty people died, and the group claims to just be getting started. Its members have threatened to carry out more attacks in heavily populated areas such as New York Citys Times Square and Washington, D.C. Shortly after the Paris killings, a married couple described as radicalized Muslims opened fire at a holiday party in San Bernardino, California, killing fourteen people. Muslims in the United States are being targeted with reactionary bigotry. Donald Trump, the unlikely front-runner in the race for the Republican presidential nomination, threatened to issue special IDs for American Muslims and ban all Muslims from immigrating to the country if he is elected. The world holds its breath, waiting for the next blow to fall.