Clichs can be quite fun.

Thats how they got to be clichs.

Alan Bennett, The History Boys

Contents

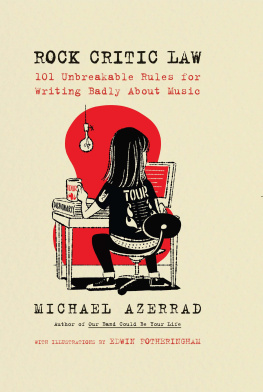

Years ago, I was on a journalism panel at a major music convention, and an earnest fellow in the audience asked, How do you keep it fresh? In a fit of snark, I shot back, Wrap it in plastic! People laughed, but Ive regretted that comment ever sincethe poor guy was asking a good question. Thankfully, my colleague Gina Arnold chimed in with some of the best advice for music critics Ive ever heard: Read fiction. Id guess that most of what Rock Critics read is other Rock Critics. And if Rock Criticism is all you read, then, in a sense, Rock Criticism is likely all youre going to write. Such an incestuous, cannibalistic literary diet probably goes a long way toward explaining the ubiquitous, seemingly indestructible clichs that I call Rock Critic Laws. Now, with blogs and podcasts and social media and all the other available internet platforms, everybody can be a Rock Critic.

Lately, its also a symptom of economics. With per-word rates plummeting, Rock Critics need to crank out more pieces than ever if they want to make something resembling a living, and its more difficult to conjure le mot juste when its 2 A.M. and youre banging out your third record review that day. Budget-slashing also means that your editor is probably too overworked to nip that sophomore effort or stinging blues licks before it hits the stands.

The thing is, Rock Critics mainly get over with insight or eloquence or wit or a big personality or just the contagious passion of the fan (or the caustic allure of the hater). We have to, because many of us dont know a lot of things that could come in very handy when writing about music. A lot of us have never performed music to large crowds, or written a song, or played take after take while the engineer and the rest of the band peer at us through double-pane glass. But maybe thats OKas the great New Yorker journalist A.J. Liebling once wrote, To understand a cockfight, you dont have to know how to crow like a rooster. Still, many of us havent studied journalism or writing; many of us dont know the difference between a chord change and a key change, or between Little Anthony and Little Richard. Thats a big reason why everyone loves to poke fun at Rock Criticseven, and especially, other Rock Critics. (Musicians also like to pile on: Frank Zappa infamously called rock journalists people who cant write interviewing people who cant talk for people who cant read.)

So sometimes Rock Critics feel a little insecure. And, like most insecure people, they try to compensate. One way is to jump on the bandwagon and echo what peers or more established critics are saying. Another is to faithfully lionize the accepted canon of artists. This way, they can feel as if they belong to a club that theyre not 100 percent sure they deserve to be in. But the best way to gain entrance is to know the password. Jargon is a shibboleth, proof of membership. Using it can make a writer feel authoritativeand it can also fool some readers into thinking the writer is authoritative. That impulse is hardly unique to Rock Criticismits in writing about sports, food, wine, philosophy, visual art, technology, politics, and any other subject in which wielding expertise is a blood sport. But only Rock Criticism abuses the word seminal.

Many Rock Critic Laws date back decades, having endured through metal, glam, prog, folk-rock, singer-songwriter music, new wave, alt-rock, Britpop, emo, neo-post-punk, and all the rest, and passed down through several generations of Rock Critics. From Paul Williamss, uh, seminal Crawdaddy! and on through publications such as NME, Melody Maker, Circus, Creem, Rolling Stone, the Village Voice, Musician, Spin, Blender, Mojo, Paste, and Pitchfork, a shorthand developed. Writers parroted a litany of rote phrases until it became a universally accepted lexicon, rarely remarked upon, much less censured. Until now.

* * *

A while back, I was reading some Rock Criticism and became peeved by a piece of boilerplate Id seen countless times before, which can be summarized thusly: When musician A plays on musician Bs album, and then musician B plays on musician As album, musician B is returning the favor. Naturally, I had to share this devastating pearl of editorial insight with the world, in much the same way as when you find something incredibly stinky and say to your friend, Hey, smell this!

So I tweeted it with the hashtag #RockCriticLaw. And then a few more of these hackneyed tropes occurred to me, constructions that anyone whos read a thousand rock music articles has read, oh, about a thousand times. And I tweeted those out too, with the hashtag #RockCriticLaw. More and more kept coming to me, and so there were tweets about dueling lead guitars and sprawling double albums and, perhaps most dreadful of all, the word moniker. Colleagues, musicians and music fans not only started liking and retweeting these things, they started sending me Rock Critic Laws of their own, and so did various musicians. (Some of which are included in this book, with my deep gratitude.) Among my esteemed peers, it became a guilty pleasure to look down the list of Rock Critic Laws and see which ones they had committed. (As stated, Rock Critics are pretty insecure.)

After Id tweeted out a few dozen Rock Critic Laws, people started saying, You should do a book!

Ridiculous! I thought, indignantly. I refuse to be one of those people who does a book of their tweets. Then again, it was kind of a funny idea...

A reporter from the New York Observer emailed mehe wanted to write a piece about my popular Rock Critic Law tweets. I answered all his questionsthen, at the end, I impetuously added, Oh, and by the way, theres a book in the works. I was bluffing, but what the hell, I said it. And the writer seemed skeptical about it, but nonetheless he played along, bless him. And so the headline of the article read: MICHAEL AZERRAD IS TURNING HIS #ROCKCRITICLAWS INTO A BOOK . Me and my big mouth.

I sent the article to my agent, who told me, Ha, ha. Now you have to do it!

And here we are.

I figured I had to do 101 Laws. One hundred is a really big number, but 101 is one more than thatthat extra push over the cliff, in the words of legendary English rocker Nigel Tufnel, whose amplifiers go to 11. At the time, I actually had fewer than fifty Rock Critic Laws, but it wasnt difficult to get to 101. In fact, I have some to spare.

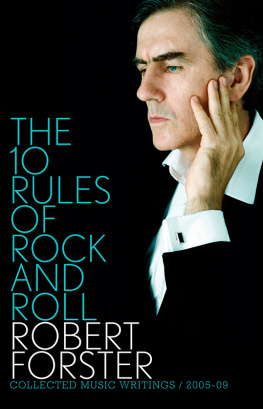

Next step: illustrations. One of the first people I met when I went to Seattle in February 1992, on assignment for Rolling Stone, was Edwin Fotheringham. Ed was a key scenester and even sangIm sure hed approve of the quotation marksin a band all too fittingly called the Thrown-Ups. (Pick hit: Eat My Dump.) He was hosting a party at his house and all the guys from Mudhoney were there. In the ensuing years, Ed went from creating album covers for OG Seattle bands such as Mudhoney, the Fall-Outs, Love Battery, and Flop to becoming a widely acclaimed illustrator, a high-class type whose work has appeared in swanky joints like the New Yorker and Vanity Fair and on covers for Verve Records. So I asked him if hed be up for creating 101 illustrations for Rock Critic Law, and not only did he accept the challenge, he devised really ingenious solutions for Laws I thought would be impossible to express visually. Ed is a smart guy and he draws real good.