BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Smart

The English Dane

Copyright 2010 Sarah Bakewell

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Chatto & Windus, an imprint of

Random House UK

Other Press edition 2010

Quotations from The Complete Works of Montaigne: Essays, Travel Journal, Letters translated by Donald Frame copyright 1943 by Donald M. Frame, renewed 1971;

1948, 1957, 1958 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. Used with the permission of Stanford University Press, www.sup.org

Production Editor: Yvonne E. Crdenas

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 2 Park Avenue, 24th floor, New York, NY 10016.

Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Bakewell, Sarah.

How to live, or, A life of Montaigne in one question and twenty attempts at an answer / Sarah Bakewell. Other Press ed.

p. cm.

Originally published: London : Chatto & Windus, 2010.

eISBN: 978-1-59051-426-9

1. Montaigne, Michel de, 1533-1592. 2. Montaigne, Michel de, 1533-1592 Philosophy. 3. Authors, French16th centuryBiography. I. Title. II.

Title: How to live. III. Title: Life of Montaigne in one

question and twenty attempts at an answer.

PQ 1643. B 34 2010 B

848.3dc22 2010026896

[B]

v3.1

For Simo

CONTENTS

Q. How to live?

MICHEL DE MONTAIGNE IN ONE QUESTION AND TWENTY ATTEMPTS

AT AN ANSWER

T HE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY is full of people who are full of themselves. A half-hours trawl through the online ocean of blogs, tweets, tubes, spaces, faces, pages, and pods brings up thousands of individuals fascinated by their own personalities and shouting for attention. They go on about themselves; they diarize, and chat, and upload photographs of everything they do. Uninhibitedly extrovert, they also look inward as never before. Even as bloggers and networkers delve into their private experience, they communicate with their fellow humans in a shared festival of the self.

Some optimists have tried to make this global meeting of minds the basis for a new approach to international relations. The historian Theodore Zeldin has founded a site called The Oxford Muse, which encourages people to put together brief self-portraits in words, describing their everyday lives and the things they have learned. They upload these for other people to read and respond to. For Zeldin, shared self-revelation is the best way to develop trust and cooperation around the planet, replacing national stereotypes with real people. The great adventure of our epoch, he says, is to discover who inhabits the world, one individual at a time. The Oxford Muse is thus full of personal essays or interviews with titles like:

Why an educated Russian works as a cleaner in Oxford

Why being a hairdresser satisfies the need for perfection

How writing a self-portrait shows you are not who you thought you were

What you can discover if you do not drink or dance

What a person adds when writing about himself to what he says in conversation

How to be successful and lazy at the same time

How a chef expresses his kindness

By describing what makes them different from anyone else, the contributors reveal what they share with everyone else: the experience of being human.

This ideawriting about oneself to create a mirror in which other people recognize their own humanityhas not existed forever. It had to be invented. And, unlike many cultural inventions, it can be traced to a single person: Michel Eyquem de Montaigne, a nobleman, government official, and winegrower who lived in the Prigord area of southwestern France from 1533 to 1592.

Montaigne created the idea simply by doing it. Unlike most memoirists of his day, he did not write to record his own great deeds and achievements. Nor did he lay down a straight eyewitness account of historical events, although he could have done; he lived through a religious civil war which almost destroyed his country over the decades he spent incubating and writing his book. A member of a generation robbed of the hopeful idealism enjoyed by his fathers contemporaries, he adjusted to public miseries by focusing his attention on private life. He weathered the disorder, oversaw his estate, assessed court cases as a magistrate, and administered Bordeaux as the most easygoing mayor in its history. All the time, he wrote exploratory, free-floating pieces to which he gave simple titles:

Of Friendship

Of Cannibals

Of the Custom

Of Wearing Clothes

How we cry and laugh for the same thing

Of Names

Of Smells

Of Cruelty

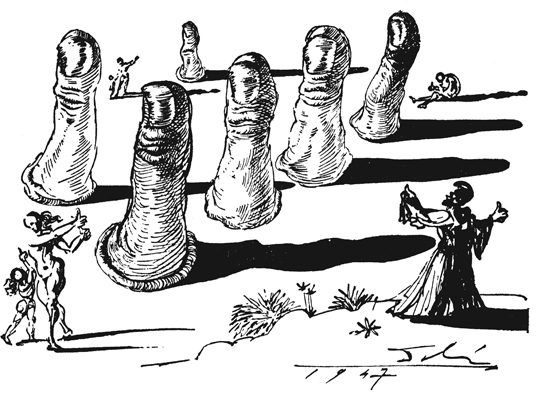

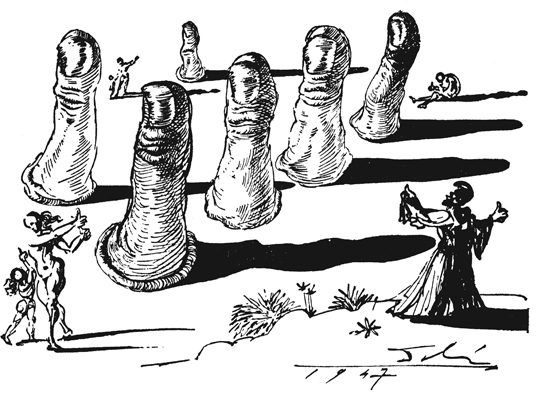

Of Thumbs

How our mind hinders itself

Of Diversion

Of Coaches

Of Experience

Altogether, he wrote a hundred and seven such essays. Some occupy a page or two; others are much longer, so that most recent editions of the complete collection run to over a thousand pages. They rarely offer to explain or teach anything. Montaigne presents himself as someone who jotted down whatever was going through his head when he picked up his pen, capturing encounters and states of mind as they happened. He used these experiences as the basis for asking himself questions, above all the big question that fascinated him as it did many of his contemporaries. Although it is not quite grammatical in English, it can be phrased in three simple words: How to live?

This is not the same as the ethical question, How should one live? Moral dilemmas interested Montaigne, but he was less interested in what people ought to do than in what they actually did. He wanted to know how to live a good lifemeaning a correct or honorable life, but also a fully human, satisfying, flourishing one. This question drove him both to write and to read, for he was curious about all human lives, past and present. He wondered constantly about the emotions and motives behind what people did. And since he was the example closest to hand of a human going about its business, he wondered just as much about himself.

A down-to-earth question, How to live? splintered into a myriad other pragmatic questions. Like everyone else, Montaigne ran up against the major perplexities of existence: how to cope with the fear of death, how to get over losing a child or a beloved friend, how to reconcile yourself to failures, how to make the most of every moment so that life does not drain away unappreciated. But there were smaller puzzles, too. How do you avoid getting drawn into a pointless argument with your wife, or a servant? How can you reassure a friend who thinks a witch has cast a spell on him? How do you cheer up a weeping neighbor? How do you guard your home? What is the best strategy if you are held up by armed robbers who seem to be uncertain whether to kill you or hold you to ransom? If you overhear your daughters governess teaching her something you think is wrong, is it wise to intervene? How do you deal with a bully? What do you say to your dog when he wants to go out and play, while you want to stay at your desk writing your book?