W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Bakewell, Elizabeth.

Madre: perilous journeys with a Spanish noun / Liza Bakewell.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-0-393-08069-8

1. Spanish languageNoun. 2. Spanish languageSyntax. I. Title.

PC4201.B35 2010

465.54dc22

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

INTRODUCTION

F EBRUARY 23, 1987. Before I met Armando for dinner, I hailed a cab. I told the driver to head south on Insurgentes, right on La Paz, up over Revolucin and into San Angel, then onto Jurez, later Hidalgo, and from there I directed him street by street. Right here, left there.

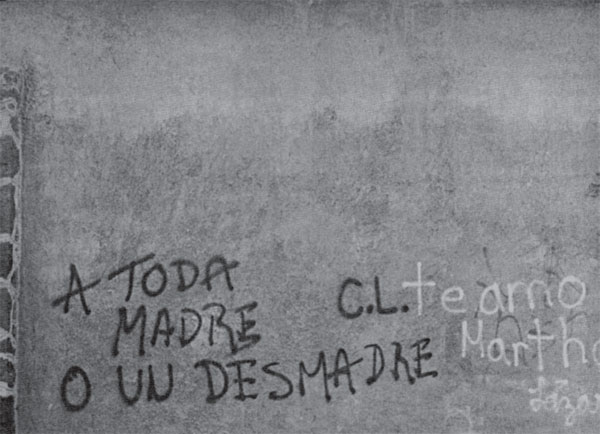

We turned onto a side street and into a neighborhood of salty white and sandy brown homes with lawns trimmed and polished as fine as I imagined the proprietors themselves. High adobe walls bordered these green oases. Wrought iron gates opened on occasion to let their owners in and out, as well as visitors and the occasional glance of a passerby. The neighborhood was interspersed with garbage-collecting empty lots, whose crumbling earthen walls struggled to maintain their separation from the street. On one of these someone had sprayed black paint, freehand, into large, unstylized letters, A toda madre o un desmadre floating it over the parched, craggy surface the way graffiti does everywhere in the world. Only this was legible.

A total mother or a dis-mother I tried to decipher it.

I had already heard, in the short time I had been in Mexico City, some extraordinary expressions with madre in them. Me vale madre was one of them.

What did it mean? The literal translation, it is worth a mother, meant nothing to me.

Worthless, someone told me.

Worthless? I asked, perplexed.

Yes, someone else reiterated. As several others explained to me, the expression can be applied to just about anythingrelationships, the governments rhetoric, the economy, the rise in random violence, dinner last night, the movie I wasted my pesos seeing.

I had never heard the expression in the Spanish classes of my college days. But when I first heard it shortly after arriving in Mexico, I held it in my hand as I might have held a strange insect. I studied it. I sought to locate it in a field guide to idiomatic Spanish insects, to no avail. Then someone translated it for me from one kind of Spanish to another kind of Spanish, from the literal its worth a mother, to the alley its worthless or I dont give a damn. I was even more baffled.

Also, around this time, I was introduced to its counterpart, the expression Qu padre! Literally it translates as what a father and is said with exclamation, but figuratively it means, How utterly fabulous, marvelous, amazing, and awesome.

Madre is worthless and padre is marvelous? I asked around.

Yes, friends and acquaintances responded, followed by, Well, ms o menos. More or less.

And so began my journey with madre .

I HAD STARTED the first day of my journey as any other. I opened the curtains that ran the full length of the living room on a side street of what many claim to be the largest city in the world. At night they concealed a solid glass wall with a door at its far end. The door opened onto a narrow balcony where six potted hibiscus plants, each my height, a little over five feet tall, hovered together near the railing. Off to the right were two folding chairs, a small, painted metal table between them, and beyond that enough room for a person to stand and look out.

On this morning, as almost every day on the high valley plains of Mexico City, the sun burst in like a warm, bright blanket tossed in my direction. It felt like cashmere as it wrapped around me. I gripped my cup of instant coffee to warm my hands, which the night within the concrete walls of my apartment had dampened and made stiff, and I stood looking out onto the locomotion below me. My neighborhood had already unlocked its eyes, stretched right and left, arisen. It had sipped its coffee and hot chocolate, taken its buses, begun to drive its cars, walked its streets, and was lined up at kiosks to buy the daily papers, then off to work. It was always ahead of me in starting the day.

I pulled open the glass door and stepped out. Down on the street poor men accepted a few coins for washing and watching over parked cars as their commuting owners sauntered off to their appointments. Flower vendors filled their buckets with water on curbsides and intersections. Shop owners clanked open the heavy metal shades locked shut the night before at closing time. Men in orange overalls swept the streets with brooms made of brush.

From the second-story terrace, I felt a part of everyones day, but also apart from it. I had moved here only a few weeks earlier from another neighborhood in the city and had begun to learn its geography, memorize its streets, the one where the outdoor market was located, the two that crossed on either side of the metro, the one whose blue wall contained a nook where a taquera a restaurant dedicated to making and serving tacoswas tucked, the side alley where the nearest cobbler worked. I stayed here for two years. I lived here. It became my home, although I never fully fit in.

There were, on occasion, other pairs of blue eyes that I passed on the streets, and other blondes. But the combination of blonde and blue-eyed made me stick out, not to mention my New England, graduate-student look of high necklines and nontailored, loose-fitting clothes. And then there was my accent. I was an advertisement for an outsider, which is why I lapsed into thinking, from time to time while living here, how I had to start rolling my r s more, buy a pair of very high heels, stop wearing black, paint my fingernails (and, also, grow them), drop my neckline, and do something with my hairother than tie it behind my head with the rubber band that held together yesterdays newspaper.

Also, I needed to stop looking so puzzled.

While I had read Spanish literature in college, this was the first time that I was surrounded by the sounds of Spanish and speaking it full time. It raised questions for me. Most of all, the word madre .

I couldnt stop asking, why, if one has any manners at all in Spanish-speaking Mexico, cant one say the word madre , the word for mother, without raising eyebrows or sometimes dodging punches?

How has it come to be that madre means whore as much as virgin and that you should give the word up altogether and talk, if you must, about ones mam ?

What happens to the ninety-nine Spanish-speaking madres seated in the auditorium after the one father enters and the Spanish feminine plural, madres , is cast aside for the male plural, padres , to describe the group of women plus one man? Do the madres cease to exist or are they there as before? Or are they there, but not as before, sequestered somewhere?