the shamans mirror

the shamans mirror

visionary art of the huicholt

hope maclean

Foreword by

Peter T. Furst

Copyright 2012 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2012

Portions of appeared as Huichol Yarn Paintings, Shamanic Vision and the Global Marketplace, Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses 32, no. 3 (2003): 311335.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 787137819

www.utexas.edu/utpress/about/bpermission.html

The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper).

The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

MacLean, Hope, 1949

The shamans mirror : visionary art of the Huichol / Hope MacLean ; foreword by Peter T. Furst.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-292-72876-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-292-73543-9 (e-book) ISBN 978-0-292-74250-5 (individual e-book)

1. Huichol art. 2. Huichol textile fabrics. 3. Huichol mythology. 4. Art, Shamanistic. 5. Hallucinogenic drugs and religious experience. 6. Symbolism in art. I. Title.

F1221.H9M22 2012

299.7845dc23 2011035818

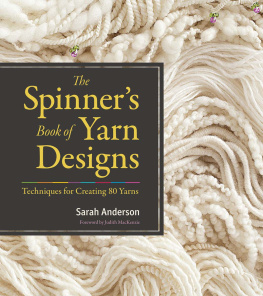

Cover image: Eligio Carrillo Vicente, Haa Naki, 2007. 24 x 24 (60 x 60 cm). This yarn painting shows a sacred site guarded by little people called Haa Naki. Photo credit: Adrienne Herron.

foreword

peter t. furst

Hope MacLeans book, the first to treat in real depth the uniquely Huichol art of painting with colored yarnsand from the inside out, that is, from the artists viewpoint, rather than only from the outside inbrings to mind the transformation from the mundane to the sacred of a yarn painting that looked no different from those made for sale, to which I was witness in December 1968 on the second of the two peyote pilgrimages in which I was a semiparticipant-observer.

There were seventeen Huichol peyoteros in our party, thirteen adults and three children, the youngest barely a week old when we started out from an overnight stay on the left bank of the Ro Lerma. Across from our temporary encampment was a rural settlement of Huichol peasant farmers and their families. They had left their homes in the mountains and canyons of the Sierra Madre Occidental for lack of arable land, but had never lost touch with their old homes and the relatives they had left behind. Nor had Ramn Medina Silva, a multitalented artist but also a lifelong peasant farmer, who led this pilgrimage, as he had in December 1966, when the late Barbara G. Myerhoff and I had the great good fortune of being the first anthropologists to witness the peyote hunt, of which the Western world had first learned at the turn from the nineteenth to the twentieth century from Carl Lumholtz, the pioneering Norwegian ethnographer of Huichol art and symbolism.

For Ramn, this was the high point of his life. Long ago he had pledged five peyote pilgrimages to his tutelaries, Tatewari, Our Grandfather, the ritual kin term for the old fire god and tutelary of earthly shamans, and Tayaup, the Sun Father, and this would be his fifth, when he would have the right to call himself a maraakame, Huichol for the shaman who not only cures but sings the many nightlong sacred chants.

Our goal, three hundred miles to the east, was the sacred peyote desert in the north-central Mexican state of San Lus Potos. The Huichol call the desert Wirikuta, and they are convinced it was the homeland of their ancestors.woman named Veradera. As soon as we camped on the first night out, I saw her pull a small rectangular piece of quarter-inch plywood from her woven shoulder bag and cover it with a thin layer of brown wax from the indigenous stingless bee. It certainly looked as though she was preparing the board for one of the yarn paintings that the Huichol have been making for sale since the 1950s and early 1960s, only smaller than usual. By the time we arrived in Wirikuta, she was putting the finishing touches on a wool yarn design that now covered the entire board; after returning it to her bag, she rejoined her companions for the hunt, literally with bow and arrow, for the little visionary succulent that, for the Huichol, is the transformation of the sacred deer.

Except for the paintings size, perhaps five inches across, in technique and appearance it was no different from those the Huichol make for the tourist trade. True, even in the Sierra you rarely see Huichols, even young children, without something in their handsa weaving, an embroidery, a string of beads for weaving into rings, necklaces, or ear ornamentswhen not otherwise engaged in agricultural or household chores. But why would someone apparently every bit as charged as any of her fellow pilgrims with anticipation of her first encounter with the ancestors and the visionary peyote distract herselfor so I thoughtwith thoughts of future income?

I could not have been more mistaken. This young artistwho, like her companions, had taken on the name and identity of one of the divine participants in the primordial peyote hunt and, also like them, was addressed as one of the Tateima, Our Mothers, for the durationturned out to be as deeply immersed as her fellow pilgrims in this, the most sacred, longest-lasting, and physically and mentally most demanding ritual in the crowded ceremonial round.

The first day in Wirikuta was spent stalking and harvesting peyote, which, because it is only a few inches across and a dusty grey-green in color, and grows low to the ground under the protection of thorny vegetation, is not easy to spot. The roots are long and come to a point, and no Huichol would fail to leave the bottom portion in the ground to assure cloning and future growth. That night, everyone assembled in a circle around the fire that was the manifestation of Tatewari, Our Grandfather, the old fire god and tutelary of human shamans, continuing what they had done in the afternoon: sharing their bounty with their companions and slowly masticating slice after slice. Some also watched for the reaction to the very bitter taste of a young boy peyotero, who was probably ten or eleven years of age.

Ramn was feeding him slices of peyote, urging, as he had everyone, to chew it well, chew it well, so that you will find your life. Whether the boy liked it was important: if he did, the Huichol say, he was likely to become a shaman; if not, it was cause only for laughter, not shame. As we could see, our young companion, his mouth full of chewed peyote, was grinning from ear to ear and nodding his approval. So the omen was favorable.

But it was the young yarn painter who would soon catch everyones attention. Sitting perfectly upright, she was taking her time before returning to everyday consciousness, so much so that lighted candles were placed around her, each a miniature manifestation of Tatewari, to shield her from hostile witches who might try to steal her soul while it was traveling out-of-body to Other-worlds. It was not the only time that she kept her companions waiting, eyes closed and with an expression of wonderment, for the return of her soul, and on each occasion her companions saw to it that she was protected by a ring of little Tatewaris.

Next page

The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper).

The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper).