Albatross

Animal

Series editor: Jonathan Burt

Already published

Albatross Graham Barwell Ant Charlotte Sleigh Ape John Sorenson Bear Robert E. Bieder

Bee Claire Preston Camel Robert Irwin Cat Katharine M. Rogers Chicken Annie Potts

Cockroach Marion Copeland Cow Hannah Velten Crocodile Dan Wylie Crow Boria Sax

Deer John Fletcher Dog Susan McHugh Dolphin Alan Rauch Donkey Jill Bough

Duck Victoria de Rijke Eel Richard Schweid Elephant Dan Wylie Falcon Helen Macdonald

Fly Steven Connor Fox Martin Wallen Frog Charlotte Sleigh Giraffe Edgar Williams

Gorilla Ted Gott and Kathryn Weir Hare Simon Carnell Hedgehog Hugh Warwick

Horse Elaine Walker Hyena Mikita Brottman Kangaroo John Simons Leech Robert G. W. Kirk

and Neil Pemberton Leopard Desmond Morris Lion Deirdre Jackson Lobster Richard J. King

Monkey Desmond Morris Moose Kevin Jackson Mosquito Richard Jones Octopus Richard Schweid

Ostrich Edgar Williams Otter Daniel Allen Owl Desmond Morris Oyster Rebecca Stott

Parrot Paul Carter Peacock Christine E. Jackson Penguin Stephen Martin Pig Brett Mizelle

Pigeon Barbara Allen Rabbit Victoria Dickenson Rat Jonathan Burt Rhinoceros Kelly Enright

Salmon Peter Coates Shark Dean Crawford Snail Peter Williams Snake Drake Stutesman

Sparrow Kim Todd Spider Katja and Sergiusz Michalski Swan Peter Young Tiger Susie Green

Tortoise Peter Young Trout James Owen Vulture Thom van Dooren Whale Joe Roman

Wolf Garry Marvin

Albatross

Graham Barwell

REAKTION BOOKS

To Rebecca, and in memory of my mother, who would have loved to hold this book in her hands

Published by

REAKTION BOOKS LTD

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2014

Copyright Graham Barwell 2014

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by Toppan Printing Co., Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780232140

Contents

Introduction

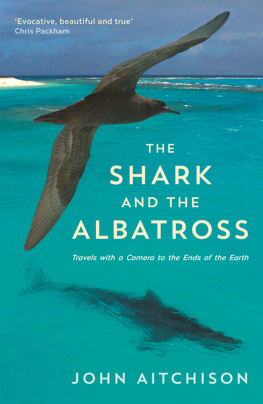

My first encounter with an albatross was when I was a boy. My father, a keen wildlife photographer, took me to see a light-mantled albatross that had been blown ashore near where we lived in southern New Zealand. It was being cared for prior to release and my father wanted to take some pictures. Like many people, even those living in areas surrounded by the oceans the birds frequent, I did not normally see such creatures in the course of my daily life, so the visit to the recuperating bird was presented as a special opportunity.

While the albatross I saw was one of the smaller members of this bird family, I confess to having only a hazy recollection of the day, though my fathers picture of the bird remains. As I grew up I did see albatrosses at a distance on other occasions, but for me the bird remained largely unknown, familiar more from photographs or Coleridges famous poem than from first-hand experience. It was only when I came to live in Wollongong, New South Wales, that I began to become familiar with the albatrosses that visit the offshore waters there in the cooler months. This familiarity came through participation in monthly pelagic trips during which the birds were regularly seen, caught and banded. The opportunity for ordinary members of the public to see such birds up close on a regular basis was completely unavailable when I was growing up.

Where once it was an almost mythical bird, familiar largely to those who visited the oceans it frequented, now it has an iconic status, representing the majesty of the natural world and signalling in its diminishing numbers the consequences of human treatment of the open seas. It is this combination of the awe which the bird inspires and the recognition of the threats it faces that produces a powerful emotional connection with it for many people today, even in parts of the world where it is not usually found.

The earliest evidence of the existence of albatrosses are fossils from the Oligocene epoch, 3423 million years ago. The fossil record from the Miocene and Pliocene epochs, 232.5 million years ago, shows that albatross ancestors inhabited the oceans of both hemispheres, with fossils being found in Japan, the United States, Britain and Bermuda, as well as in Australia, South America and South Africa. In the Quaternary Period the birds seem to have disappeared from the North Atlantic, though live birds do turn up there occasionally and may stay for many years. In evolutionary terms, their closest relatives are other seabirds the petrels and shearwaters, the storm-petrels and diving-petrels, which together occupy a wider range of oceanic habitats than the albatrosses. These families share a common characteristic of having tubular nostrils in a prominent position on top of the bill.

Light-mantled albatross recuperating after having been blown ashore. The first albatross I ever saw.

| SOSSA members measuring and banding a wandering albatross off Wollongong. |

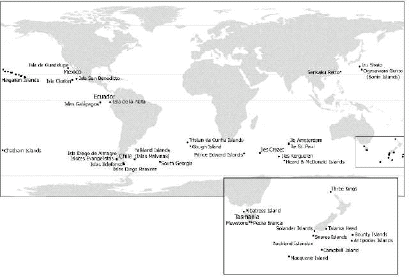

Today albatrosses are confined to the Southern Ocean, the cooler waters off Peru and Ecuador and the North Pacific. They are not found in most of the tropics, except around Hawaii and the seas from the Galapagos Islands to the South American mainland. They breed usually on isolated oceanic islands and come into contact with humans on the oceans. They spend most of their lives at sea, mainly in pelagic waters, though they may frequent inshore waters in certain circumstances, especially when food is readily available. They generally come ashore only to breed, though some birds may be blown onto land by very strong winds.

Map of albatross breeding areas.

Because albatrosses breed in areas remote from most human populations and spend so much of their lives at sea, they have not been as intensively studied by ornithologists as some bird species, so new knowledge is constantly being discovered. Even the number of species has been revised, with the thirteen species recognized up to 1998 having been expanded to 21 or 22 species today.