CONFESSIONS OF AN

IRISH REBEL

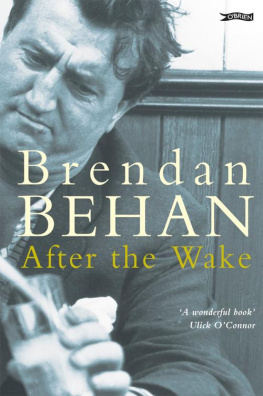

Brendan Behan was born in Dublin in 1923. He was sentenced to three years in Borstal in 1939 for his activities in the IRA.

He became a dominant literary figure almost overnight with the 1956 production of his play 'The Quare Fellow', based on his prison experiences. This recognition was reinforced by the success of Borstal Boy and his second play, "The Hostage'.

Brendan Behan described his recreations as 'drinking, talking, and swimming', but no factual description could do justice to his flamboyant, larger-than-life character. Generally regarded as irreverent and unpredictable if not actually dangerous, there was nonetheless no publicity which ever obscured his marked talents or his great understanding of human nature.

Brendan Behan died in 1964.

ALSO BY BRENDAN BEHAN

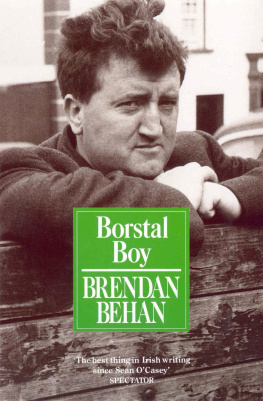

Borstal Boy

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 9781409043744

Version 1.0

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Published in the United Kingdom in 1991 by

Arrow Books

Copyright Beatrice Behan and Rae Jeffs 1965

The right of Brendan Behan to be identified as the author of thiswork has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,Designs and Patents Act, 1988

This electronic book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

First published in the United Kingdom in 1965

by Hutchinson & Co

Arena edition 1985

Reissued 1990

Arrow Books

Random House Group Ltd

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London, SW1V 2SA

www.rbooks.co.uk

Addresses for companies within The Random House Group Limitedcan be found at: www.randomhouse.co.uk/offices.htm

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781409043744

Version 1.0

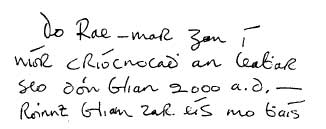

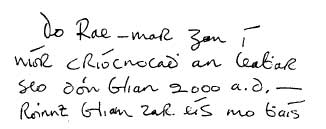

A facsimile reproduction of Brendan Behan's

handwritten dedication, translated below

TO REA

without whose help this book

would not have been written until

at least 2000 A.D. many years

after my death

PREFACE

by Rae Jeffs

IT was in the spring of 1957, seven years before his death, that I first met Brendan Behan. He had come to the London offices of Hutchinson, his publishers, to deliver the manuscript of Borstal Boy.

I knew little about him, except that he was the Irish author of an extremely good play, The Quare Fellow, and that he was the star of one of the most talked-about television interviews of 1956.

When I met him, he was standing next to a table, a formidable figure, with his unruly hair cascading over his forehead and his clothes arrayed around him in the best fashion they could without the help of the wearer. His wife, Beatrice, sat in the corner at his side, and I was at once struck by the deep unspoken understanding that obviously existed between them.

We were introducedBrendan's introductions to the opposite sex could hardly be described as formaland I was asked to give a prcis of my life up to that very moment. He listened quietly and was genuinely interestedan essential facet of his character which he lost only a few months before his death interrupting only when he felt I had glossed over an important detail. When he learned that I came from Sussex, he was obviously delighted. Apparently he had been extremely well treated in the short time he had spent in a Sussex prison, and as a result he had a warm regard for anyone coming from that county.

The introductions over, Brendan, whose thirst took small account of licensing hours, called for a drink. With vicarage garden-party decorum, I enquired whether it would be tea or coffee?

'Do you call that a drink?' he roared, interpolating a stream of unbridled anglo-saxon words which would not normally be heard in a publishers' office.

And so began the first of my many lessons in nonconformity. Somehow I managed to get hold of a bottle of whiskey, and I returned triumphantly to the office, as much exhilarated by my feat as was the man himself on getting it.

For the rest of the afternoon, I was entertained by numerous stories which were not altogether easy to follow for the uninitiated, for Brendan had a most captivating way of unexpectedly breaking into song. He had an unlimited repertoire of folksongs and Dublin ballads which he would sing enchantingly by the hour in a light lilting brogue.

Suddenly, without word of warning, as if on castors, he glided to the door, Beatrice followed, and off down the passage shouting, 'Sln leaf, to the wide-eyed astonishment of the passers-by. I raced after him as I remembered the precious manuscript, still not delivered, only to receive the casually imparted information that he had 'left it at the BBC and would 'go and get it'. I remember it was five-thirty by the clock in the street opposite, but the significance, in those early days, was lost on me. Some time later, I started out to look for him, but I did not have to go very far. I heard his voice coming from The George singing, somewhat more lustily than before, the same Dublin ballads.

Under the rumbustious bravado, Brendan was courteous, considerate and absurdly generous. Every person in the pub that evening was clustered round him as though drawn by a magnet, and it would have taken a bigger fool than myself not to discover the largeness of the heart that ticked behind the showman's mask. I had simply started out on a business mission, but in a matter of hours, I lived a lifetime. It was a most remarkable experience, and to those who poke the finger of scorn at objects of popular adulation, I can only say it was as though a five-hundred watt light had suddenly gone on. It wasn't necessarily that things were dull before, but that Brendan's presence produced an overwhelming current of electricity quite beyond the ordinary. He was not then a world-renowned figure, or the all-important copy for the morning's editions. He was a man being himself, more alive than the rest of us, and our batteries were charged with a vitality which, for me at any rate, changed the whole conception of life.

Throughout the following year, my connection with Brendan was mainly that of a public relations officer, and it was in this capacity that I began to pierce through his external ferocity, which is the life force of nearly all artists, and to discover the innocence, the tenderness and the sensitivity behind it.

Before any public appearance, he would assume a completely different personality. As we neared the television studios or the newspaper offices for an interview, I could almost see him building up the bricks of the wall that protected him from himself. Beads of perspiration would break out on his forehead, and he would be cruel, abusive and arrogant.

He knew he had to live up to his reputation as the tough I.R.A. rebel, the man who would assault not only others, but himself as well, rather than conform. He did not dare reveal that the ugliness of his experiencesdeath, bloodshed and prison routinehad not really touched the vital part of him. His essential being was strangely unaffected by the many painful events in his life, and this cloak of violence and abuse was necessary to hide his vulnerability. When the strain of impersonation became too much, a bout of drinking would followthe best soporific of all. But when he realised this bulwark of self-protection was unnecessary, he became almost childlike in his frankness and candour.

Next page