This book was my idea, but I had help along the way. Beatrice Behan was always enthusiastic, helpful and courteous; she made our collaboration a pleasure for me. Colbert Kearney wrote an excellent book. Rory Furlong, Edward Mikhail and Christopher Logue answered my letters and my questions.

I had help too from the staffs of the National Library in Dublin and the Periodicals Department of the British Museum and from Nra de Brn and the staff of the library of University College, Cork.

Michael OBrien was the good publisher; he trusted his instincts. Jean Barry typed the manuscript. Alison helped at the British Museum and Loudon first took me to The White Horse.

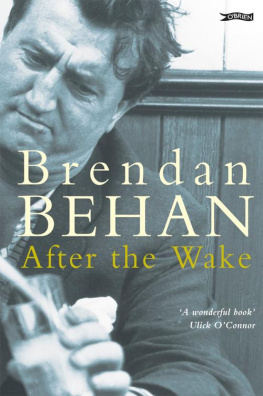

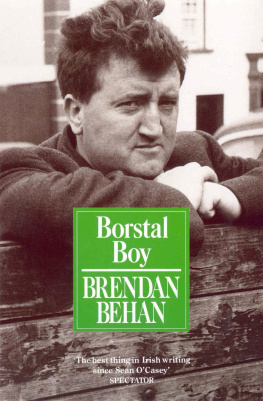

Brendan Behan was born, in Dublin in 1923, into an Irish Republican family and he soon found the households politics to be his own. In 1940 he began almost two years detention in Borstal in England for complicity in acts of terrorism. When he was arrested, he made this statement: My name is Brendan Behan. I came over here to fight for the Irish Workers and Small Farmers Republic, for a full and free life, for my fellow countrymen, North and South, and for the removal of the baneful influence of British Imperialism from Irish affairs. God save Ireland. He was sixteen years old.

Two years later, he began five years of his prison sentence for shooting at a detective during an I.R.A. commemorative ceremony in Dublin. Many thought him lucky to escape hanging for this act. Instead he was sentenced to fourteen years penal servitude and released under a general amnesty. In 1947 he was arrested again, this time in Manchester, having helped in the escape of an I.R.A. prisoner, and he was sentenced to four months imprisonment.

Behan seems to have appreciated his terms of confinement he considered them his university and from the first of them he gleaned the material for his best-selling autobiography, BorstalBoy, and from the second and third, material for plays and stories and even the language itself for the poems and the play he wrote in Irish. Detained in the Curragh, he studied the Irish language and literature under Sen Briain and Mirtn Cadhain and began to conceive of the possibility of rebuilding a native Irish culture. The play, AnGiall, was later transformed into TheHostage.

Perhaps there was something predictable about the course of events of his early life. One of the titles considered for his memoir of Borstal, Bridewell Revisited, has about it an air of inevitability as well as of wit. The excellence of his writing could not have been foretold. But Behan had two exceptional gifts as writer and as showman. Tragically his prowess for one would ultimately destroy the talent hed begun to question for the other.

Writing in Irish afforded a way for Behan to realise his literary and political aspirations. In 1946 he published his first poem in Comhar; he had published juvenilia in TheWolfeToneWeekly,TheUnitedIrishman,Fianna:TheVoiceofYoungIreland and other radical journals. This poem, FilleadhMhicEachaidh, a eulogy for Sen McCaughey, an I.R.A. officer who died on hunger-strike in Portlaoise, was later incorporated into AnGiall.

In the next few years he published other poems in Comhar,Envoy and Feasta, and he was the youngest contributor to Sen Tuamas Nuabharsaocht (1950).

By the early 1950 s he was writing in English again and he published short prose pieces in various magazines in Paris. In MyLifewithBrendan, his widow Beatrice recalls, Brendan had talked to me at great length about Paris. Like James Joyce he had spent penniless years there, and he had written pornography to survive A detective story, TheScarperer, by Emmet Street was serialised in TheIrishTimes in 1953. In 1955 he married Beatrice Salkeld.

Nineteen fifty-four was the turning point in Behans career. It was the year in which TheQuareFellow was first produced by the Pike Theatre in Dublin. Two years later this play was accepted by the Theatre Royal in London. In 1958 TheHostage was first produced and BorstalBoy was published. Brendan Behan had quickly become an international celebrity, the darling of critics and the popular media. The limelight proved too much a distraction from the completion of further serious work. Plays and prose were left unfinished, ideas and promises unfulfilled.

AftertheWake is a book of uncollected and unpublished short prose pieces. It includes work of acknowledged excellence, The Confirmation Suit and A Woman of No Standing; of sombre detail, The Execution; and of lively autobiography, I Become a Borstal Boy The unpublished pieces and they include a short story called The Last of Mrs Murphy and the opening section, all that exists, of an unfinished novel, The Catacombs are infused with compassion, wit and perceptive comment. The eponymous story, After the Wake, is arguably the authors finest It displays a degree of feeling that is honestly, humanely and courageously reported.

The selection contains all the hallmarks of the authors talent an ability to bring characters to life quickly and unforgettably, a sharp ear for dialogue and dialect, and a natural vocation for story-telling. His pervasive themes are rampant the obsession with nuances of class and social structures, the inclination towards insurrection and rebellion, and the over-riding sense of moral justice. Grim situations are relieved by clemency and humour. Above all, the delicacy and holiness of human tenderness and sympathy is depicted vividly against usually unsympathetic backdrops.

The first of these stories, The Last of Mrs Murphy, was submitted to Radio ireann from the Behan home-place in Crumlin in the early 50s. The script was marked for the attention of Francis MacManus or Mervyn Wall, and Mr. Wall thinks it was broadcast as part of a series of talks Brendan Behan gave around that time. It is very much a Dublin story, the characters are easily recognisable as fictional neighbours of those in The Confirmation Suit. It is a story about fellowship with a surprising and spirited twist.

I Become a Borstal Boy, prototype of BorstalBoy, was accepted by Sen Faolin for publication in TheBell in June, 1942, sixteen years before the appearance of the extended and altered memoir. It tells of events after the authors first arrest and shows a conflict of emotions between the narrators personal responses and the expected stance of one cast in his position for the Cause.

This conflict is highlighted in The Execution which has only been published before in a limited edition (Liffey Press, Dublin, 1978) and which I have transcribed from the authors manuscript. In his handwriting all the bs are capital Bs, there are commas around almost every phrase, and almost every sentence is a separate paragraph. I have made certain modifications. The Execution owes much to Frank OConnors story, Guests of the Nation, though it is shorter and less polished. The implication of the job in hand, its human seriousness, is conveyed in one sentence: I never liked him much before but I felt sorry for him and sorrier for his people. The final act exposes mans confusion in political deed and fervour.