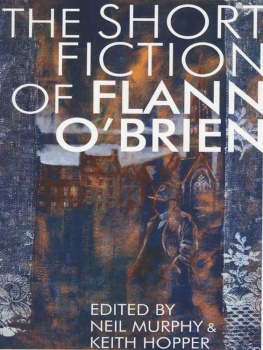

Warm thanks are due to Breandn Conaire for translating most of the Irish material, and to Susan Asbee for making available to me the extracts from At Swim-Two-Birds; to Tess Hurson, Aibhistn Mac Amhlaigh, Anthony Cronin and very many others for help and encouragement; to Mrs Evelyn ONolan for smiling on the project; and to Eoghan and Biddy, Lucy and Julie, and the entire Wyse Jackson family for being themselves. I would also like to thank John Ryan, Peter Costello, and, for the pieces included here by her late husband, Mrs Kathleen Kavanagh.

On April Fools Day 1986, exactly twenty years after the death of the author of this book, there was a strange gathering in Dublin. It was the first international symposium devoted to the life and work of Flann OBrien. Incorporated into each days proceedings was an event oddly titled Late Evening Criticism, during which delegates and members of what could be called Literary Dublin met, drank Guinness, and then proceeded to criticise each other. One morning, John Ryan, artist, writer and old friend of Flann OBrien, set off from the symposium with a crocodile of professors, students, Mylesmen and corduroys Myles na Gopaleens term for personages of undefined literary pretensions. The object of this pilgrimage was to visit some of the many hostelries where your man had reputedly found inspiration, to look at them, and to soak up, among other things, the ambience. In just such a spirit did the devout penitents of the Middle Ages visit the holy wells of Ireland and partake of the holy liquid therein. It was not until the Holy Hour (when the pubs shut) that the crocodile shuffled, bedraggled but happy, back to the symposium. Flann OBrien, Myles na Gopaleen and Brian ONolan could not have disapproved .

Apart from the celebratory festivities during the three days of the symposium, the emphasis among the more studious delegates was primarily on the novels of Flann OBrien. This is understandable : a novel must have a beginning (or, in the case of At Swim-Two-Birds, three beginnings), a middle and an end; it can be more satisfactorily tackled as a unit, whereas it is not so easy to discuss collections of shorter pieces which by definition lack a collective structure. There is another reason, however. Much of Brian ONolans most interesting and entertaining work has never been published in book form. Most of his writings from the thirties, for example, which include some of his funniest excursions, and which display several nearly unknown aspects of his work, have lain in almost complete obscurity since then, and it is this material which forms the basis of the present collection.

Like Gaul and good sermons, the thirty-five years of ONolans writing life can be divided into three parts. For the first ten years, say, between 1930 and 1940, he was seeking a voice. During the next ten years or so, he had found it. After about 1950, he had become that voice. Throughout, he could write elegantly, intelligently and hilariously, and often with what he once called the beauty of jewelled ulcers. The things that changed were the tone, the style, the language, and the pseudonym, or pen-name.

There are two main reasons for the use of a pen-name. The first is obvious: to provide anonymity for proprietys sake or for professional purposes. As a civil servant, Brian ONolan needed to be able to say, as he once did when accused by his superiors of having written an article signed by one John McCaffrey, I no more wrote that than I wrote those things in the IrishTimes by Myles na Gopaleen. The second reason is that the use of a pen-name makes it far easier for some people to write imaginatively and freely, and, indeed, to write well. Try writing to the papers under a false name and you will see what I mean. You will be able to say all sorts of disgraceful things without being accused of believing them.

It is almost impossible to discover from ONolans pseudonymous writings what the man behind them really believed. Pseudonyms were central to his creative impulse. He rarely used his real name, and when he did it was usually in its Irish version, Brian Ua Nuallin, or some variant thereof. Other names that he adopted, apart from Myles na Gopaleen and Flann OBrien, include Peter the Painter, George Knowall, Brother Barnabas, John James Doe, Winnie Wedge, An Broc, and The OBlather. The list is by no means complete. It has been said, however, that he began life as who he really was, and ended it as Myles. The whole of Ireland, as well as most of his acquaintances, knew him simply as Myles, and he thus gradually lost the freedom of expression that his persona, Myles na Gopaleen, had given him. In the later CruiskeenLawn columns in the IrishTimes, what Myles wrote, Myles believed. Or so people thought. It was probably a response to ONolans realisation of this effect that prompted him to give birth in 1960 to George Knowall, the hectoring polymath of MylesAwayfromDublin.

In this collection, however, there are few of the acerbities of George Knowall. Brian ONolan, here, is above all an entertainer , a gas man. He began his literary career proper with stories and articles, generally humorous in intent, which he wrote in Irish, his first language. (His father had discouraged the use of English at home, and the young Brian is said to have taught himself to read the language first, by looking at comics, and then, at about the age of seven, by tackling Dickens.) These early Irish pieces, a few of which have been included here, show ONolan already trying out ideas and techniques that he was to use in his greatest Irish work, An Bal Bocht (ThePoorMouth). They were published in the early thirties while he was a student at University College, Dublin. The College magazine Comhthrom Finne, of which he was to become editor for a time, printed his first articles in English, and Brother Barnabas, the most important pen-name he used at this time, was celebrated as an oracle and commentator on College matters. Like Myles na Gopaleen ten years later, the eccentric monk practically became a person in his own right, and, indeed, on 30 April 1932 the magazines gossip column reports that Mr B. ONuallin was heard speaking to Brother Barnabas in a lonely corridor: Brian, I had to come back from Baden-Baden. Thats too bad, then.

At the end of his college career, ONolan, together with some friends, notably his brother Ciarn, Niall Montgomery and Niall Sheridan, who was to appear thinly disguised as Brinsley in the novel AtSwim-Two-Birds, founded Blather, variously described by itself as The only really nice paper circulating in Ireland, Irelands poor eejit paper, The voice from the back of the hall and The only paper exclusively devoted to the interests of clay-pigeon shooting in Ireland. It was inspired by Razzle, an English comic magazine of the period, and contained cartoons, some of them drawn by ONolan, silly verse, mock political pieces, short stories, and a host of other miscellaneous pieces which display the warped and imaginative view of things that we have come to expect from ONolan. Again, several of the comic devices for which Myles/Flann is known appear in their early forms in the paper, but, that apart, Blather remains vastly entertaining still, and a generous selection from its short life is reprinted here.

It is extremely difficult to identify for certain which of the pieces in Blather and ComhthromFinne were actually written by ONolan, which were collaborations, and which were the work of other contributors. There was a common sense of humour and style among his friends at the time, and it is likely that there was considerable discussion of what was to go into print. However, what is certain is that ONolan wrote most of it, and furthermore that his was the creative guiding force behind all of it. The humour was his own, or he made it his own. The same