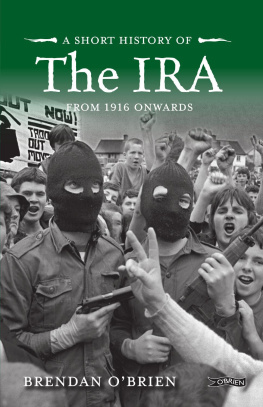

OBrien - A Short History of the IRA: From 1916 Onwards

Here you can read online OBrien - A Short History of the IRA: From 1916 Onwards full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Lightning Source Inc. : TheOBrien Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

A Short History of the IRA: From 1916 Onwards: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Short History of the IRA: From 1916 Onwards" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

OBrien: author's other books

Who wrote A Short History of the IRA: From 1916 Onwards? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

A Short History of the IRA: From 1916 Onwards — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A Short History of the IRA: From 1916 Onwards" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

1916

The original leaders of the Irish Republican Army would be astonished to find now, a century later, there is still no thirty-two county Irish Republic. The received wisdom of the 1920s was that the new artificial construction, the Border dividing Ireland into the six-county Northern Ireland province of the UK and the twenty-six county Irish Free State, would wither with time. With it would wither Britains last vestiges of power in Ireland. Yet the unthinkable was happening. Crossing a new millennium another generation of IRA activists was fighting the same fight. The Partition of Ireland and British jurisdiction over Northern Ireland had become more, not less, embedded over the years and gained more, not less, enduring nationalist acquiescence. Looking beyond the 2000s, an independent unitary Irish state, ruled from Dublin, was widely regarded as a remote and impossible dream. For a great many would-be Irish republicans, even the dreaming had stopped.

Yes, the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 rekindled hope. But glaigh na hireann had been forced to accept unthinkable compromise, despite being more entrenched than at any stage since the 1920s. The modern IRA, re-constituted in December 1969 and on the offensive for most of the time since August 1971, had sustained the longest-ever unbroken armed resistance against British rule in Ireland. Yet they had not achieved their goal. When the Army Council confidently declared a unilateral cessation of military operations in August 1994 to enter round-table negotiations, they received no guarantee of winning the Republic. They had neither been victorious nor had they been defeated. Not to be defeated by overwhelming British forces during almost a quarter of a century of armed action was in itself regarded as a major success. But with no victory in sight ambitions had become chastened. The unambiguous demand for a British withdrawal from Ireland had been replaced by the language of compromise. And the fact that the IRA had effectively come to recognise the legitimacy of the southern state, for so long regarded as an illegal puppet regime, was a very real manifestation of their failure.

When the IRAs cessation of violence broke down in early 1996, most of the volunteers and local commanders were happy to be back in action, back at the British, ready as always to finish the business. One more push and the British would be forced to face their responsibilities, as it was now ambiguously put in Army Council statements. The resumption of armed struggle, however, reopened old divisions over politics and armed force; divisions which had bedevilled modern Irish separatists ever since Pdraig Pearse publicly proclaimed the still-elusive thirty-two county Irish Republic around noon on Easter Monday, 24 April 1916. That was, in effect, the time and date when the Irish Republican Army was born.

The 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin, as begun by Pearses proclamation, was not a neat and tidy affair between a newly formed Republican Army and the British forces. In the first instance, it was not so much a rising, more an attempted military coup, secretly plotted by a handful of mainly unknown men. The self-proclaimed Army of the Republic was at first an uncertain collection of dedicated militarists; primarily Irish Volunteers supported by the Irish Citizen Army and even smaller groups like the Hibernian Rifles, all under the command of the Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

This was no cohesive fighting force welded together over time with a disciplined structure and ideology. Some were separatists but not republicans. The Irish Volunteers, founded in 1913, was a broad church numbering close to 200,000, few of whom were armed and most of whom in 1914 followed the lead of John Redmond, moderate leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, in pledging Irelands support for Britain in the Great War against Germany. Those Volunteers who dissented from Redmonds call numbered just over a thousand under Chief-of-Staff Eoin MacNeill. And even when the Rising came in 1916 it was started against the wishes of MacNeill, who correctly argued that it would end in military disaster and public hostility.

Ideologically, the small Irish Citizen Army, formed by the revolutionary socialist trade union leader James Connolly, was a group apart. Connolly had far more radical ambitions than people like Pdraig Pearse and the traditionalist Roman Catholic Hibernian Rifles group, connected with the Ancient Order of Hibernians. Alongside this collection of disparate organisations was a new political grouping called Sinn Fin, meaning Ourselves Alone. At the time Sinn Fin was more separatist than the Irish Parliamentary Party but, in proposing a dual monarchy for Britain and Ireland, was not republican.

Where there was cohesion was within the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), the main driving force behind the attempted military coup. The IRB was a dedicated, secretive body formed in March 1858, first called the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood, avowedly republican and militaristic with support among the immigrant Irish in the emergent United States, where it was known as Clann na Gael.

Despite these uncomfortable combinations, a single military group had come together, acting within the terms of the decision adopted on 9 September 1914, by the Irish Republican Brotherhood, to strike against Britain at some time during the war which had just begun. When it came to it, the bulk of Irish separatists were unwilling to take up arms against what was then their own legal government at a time of war. Many had enlisted and were dug into trenches in foreign fields, fighting Britains fight. In addition, the Liberal government in London had developed a policy of Home Rule for Ireland. The fuse of armed resistance to British policy came not from republicans demanding more but from the Ulster Volunteers demanding less. Formed in 1912 these Unionists were pledged in blood to fight against Home Rule, a pledge backed in part by elements in the British Conservative Party and in the British Army. Still, some measure of independence for Ireland, albeit under the Crown, was a probability at wars end. Given the electoral strength of Redmonds Irish Party, the advocates of Home Rule, it seemed a majority of Irish people would have been content with that.

It was virtually unimaginable that the 1916 Proclamation declaring Ireland a republic, read on that ordinary Easter Monday to a bemused and disinterested Dublin population outside the General Post Office, would in time become the bedrock of 20th century Irish republican ideology. Headed POBLACHT NA HIREANN: THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT OF THE IRISH REPUBLIC TO THE PEOPLE OF IRELAND , it read:

Irishmen and Irishwomen: in the name of God and of the dead generations from which she receives her old tradition of manhood, Ireland, through us, summons her children to her flag and strikes for her freedom.

Having organised and trained her manhood through her secret revolutionary organisation, the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and through her open military organisation, the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army, having patiently perfected her discipline, having resolutely waited for the right moment to reveal itself, she now seizes that moment and, supported by her exiled children in America and by gallant allies in Europe, but relying in the first on her own strength, she strikes in full confidence of victory.

We declare the right of the Irish people to the ownership of Ireland and to the unfettered control of Irish destinies to be sovereign and indefeasible. The long usurpation of that right by a foreign people and government has not extinguished that right nor can it ever be extinguished except by the destruction of the Irish people. In every generation the Irish people have asserted their right to national freedom and sovereignty: six times during the past three hundred years they have asserted it in arms. Standing on that fundamental right and again asserting it in arms in the face of the world, we hereby declare the Irish Republic as a Sovereign Independent State; and we pledge our lives and the lives of our comrades-in-arms to the cause of its freedom, of its welfare and of its exhaltation among the nations.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

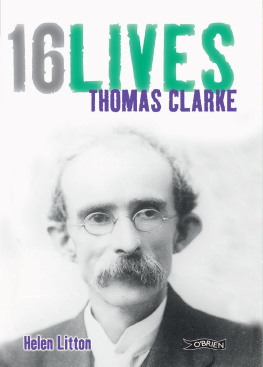

Similar books «A Short History of the IRA: From 1916 Onwards»

Look at similar books to A Short History of the IRA: From 1916 Onwards. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A Short History of the IRA: From 1916 Onwards and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.