The construction of larger fortifications belongs to the iron age after 500 BC and many forts of varying shapes and sizes survive. The most impressive is Dn Aengus on Inis Mr, the largest of the Aran Islands in Galway Bay. It is a huge semi-circular fort built on the edge of a sheer cliff, 300 feet (about 100m) over the sea. These forts were clearly meant to give shelter to people, and perhaps to their animals, during an attack. What is not clear is who the attackers were. Dn Aengus must have taken many years to build and, as it is some distance from fresh water, could not withstand a long siege. One recent theory maintains that these forts had little to do with defence and were centres of worship and ceremonial. It is this element of mystery, as much as its awesome aspect, that attracts visitors to Dn Aengus in great numbers.

The Griann of Aileach, in Donegal near the border with Derry, and Staigue Fort, near Caherdaniel in Kerry, are among the most spectacular ring forts on the mainland. Dn Aengus is favoured by those whose interest in antiquities is small but who appreciate the panoramic view from the cliff-top that extends from the coast of Kerry to the farthest tip of Connemara.

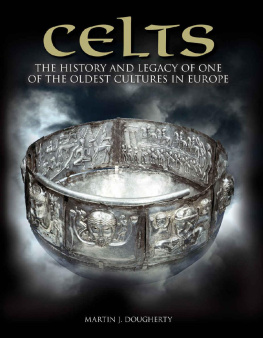

The Celts arrived from central Europe probably as early as the sixth century BC, with further groups arriving at later stages. They were reputed to be clever, good craftsmen and brave to the point of foolhardiness. Diodorus Siculus, a Roman historian, wrote of the Celts in the first century BC in a passage which is not entirely unkind to them: Physically the Celts are terrifying in appearance, with deep-sounding and very harsh voices. In conversation they use few words and speak in riddles, for the most part hinting at things and leaving a great deal to be understood. They frequently exaggerate with the aim of extolling themselves and diminishing the status of others. They are boasters and threateners and given to bombastic self-dramatisation and yet they are quick of mind and with good natural ability for learning As warriors they were no match for the Romans who, with their superior weapons and tactics, eventually drove them to the extremities of the continent.

Celtic Ireland was divided into about 150 little kingdoms and five provinces, each with its own king. (Four of them Ulster, Munster, Leinster, Connacht still survive as units, mainly in sport, but the use of the name Ulster to describe Northern Ireland, which contains only six of the original nine counties of Ulster, is resented by those who take their history seriously.) There were no towns and the cow was the unit of exchange. The Celts were great believers in the extended family as a social unit. Each province was dominated by one family, but succession to the throne was determined not by primogeniture but by election. The elders of the various clans had the right to vote, and this gave rise to serious faction fighting. For this reason one writer described the Irish of that period as the spleen-divided Gaels. However, the country was united by a common language and culture. Of the Celtic languages surviving today Irish, Scots Gaelic, Welsh, Breton and, theoretically at least, Manx and Cornish Irish is the only one with an independent state to support it.

The strongest strands in the Celtic culture, apart from the language, were religion and law. The religion was druidism, administered by a priesthood of druids. The laws were written and interpreted by a class of professional lawyers known as brehons. There was an elaborate code of legislation based on the community and the extended family. Fosterage of children, who were then brought up by the foster family, was common and forged links between different families. Much conflict erupted later when the Norman invaders tried to impose their totally different code.

One of the differences between the two codes concerned the status of women who, in the Celtic system, had a high standing. Women had the right to own and to inherit property and also the right to divorce. In legend, Queen Maeve of Connacht is portrayed as a warrior and a feared leader of men. In reality, Grace OMalley, the seafaring contemporary of Queen Elizabeth I of England, made war on her enemies along the west coast on land and on sea. Known as Granuaile, she entered into marriages on her own terms and on occasions retained her partners lands after declaring that the contract was at an end!

There was also great respect for learning, and the poet (file) was both admired and feared. To be lampooned by the more ferocious satirists was a fate worse than death and their patrons had to be careful not to offend them. On one occasion a poet who had been offended by King Guaire went on a hunger strike on the threshold of the palace. Even though the king came personally offering food, the poet, Seanchn, died. W. B. Yeats based his play