Contents

The Twilight of Unionism

Geoffrey Bell was born in Belfast and has written extensively about Ireland and British attitudes to the Troubles, past and recent, for print, television and exhibitions. These include Protestants of Ulster, and the documentary Pack Up the Troubles for Channel 4.

The Twilight of Unionism

Ulster and the Future

of Northern Ireland

Geoffrey Bell

First published by Verso 2022

Geoffrey Bell 2022

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 388 Atlantic Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11217

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-693-0

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-695-4 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-694-7 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Contents

My mother read to me from the Bible. It says that God created the world, but it doesnt say anything about borders. You cant cross a border without a passport or a visa. I always wanted to see a border properly for myself, but Ive come to the conclusion that you cant. My mother cant explain that to me either. She says, A border is what separates one country from another. At first I thought borders were like fences, as high as the sky. But that was silly of me, because how could trains go through them? Nor can a border be a strip of land either, because then you could just sit down on top of the border, or walk around in it, if you had to leave one country and werent able to get to the next. You would just stay on the border, and build yourself a little hut and live there and make faces at the countries on either side of you. But a border has nowhere for you to set your foot. Its a drama that happens in the middle of a train, with the help of actors who are called border guards.

Irmgard Keun, A Child of All Nations (1938), translated by Michael Hofmann (2008)

This book is for Cassidy and Orla.

May you grow up to see fewer borders.

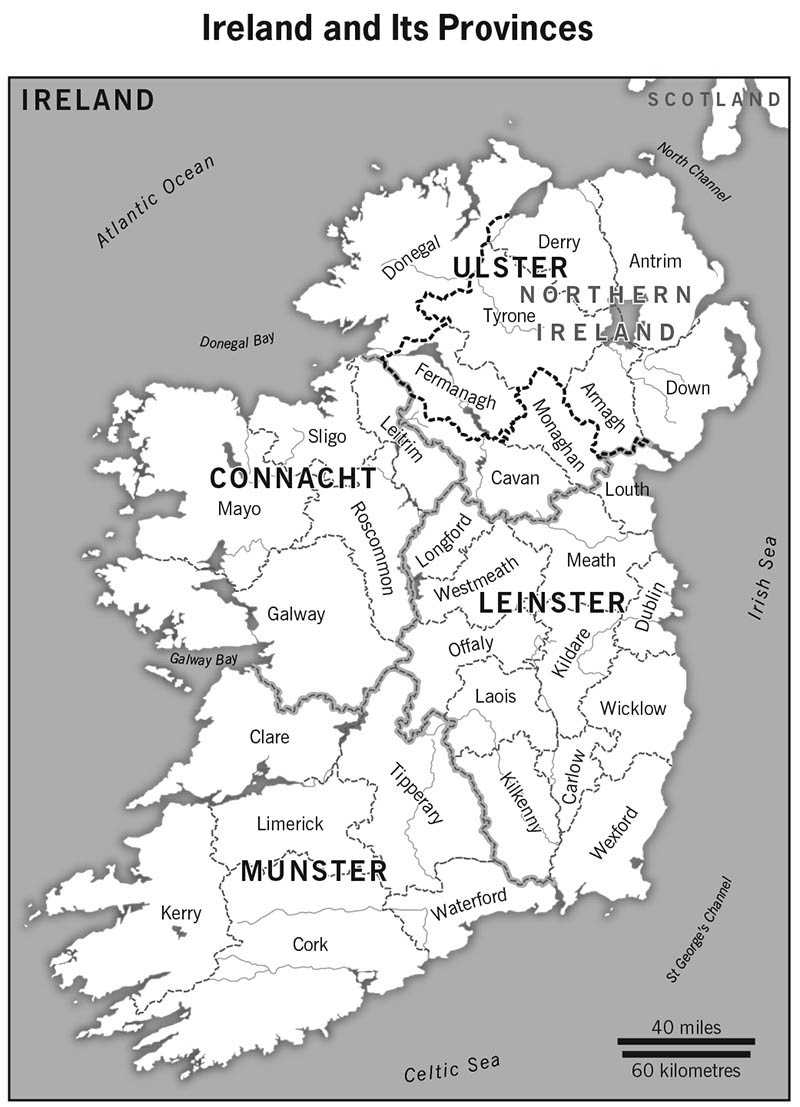

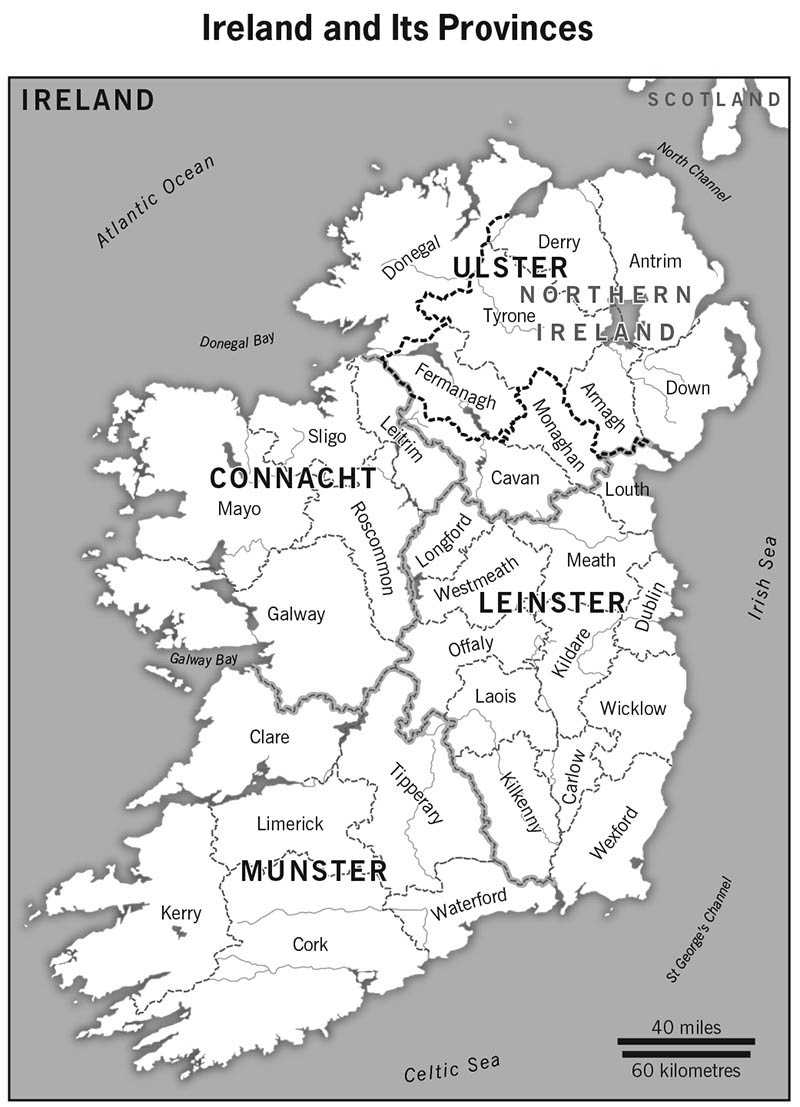

The grey line marks the historic boundaries of Irelands four counties of Ulster, Connacht, Leinster, and Munster. The blacked dotted line is the political boundary of Ulster as created at partition in 1921.

In The Protestants of Ulster, first published in 1976, I wrote that this community was the most misunderstood and criticised in western Europe. This intentionally provocative statement proved unintentionally prophetic.

I was referring to the Protestant community of what is known as Northern Ireland. Despite much collected evidence and many contested opinions, a lack of comprehension of this community remains common, certainly among those with only a passing interest in exploring the politics and history of the island of Ireland and its relationship with its nearest neighbour. Compounding this, in the last few years there has been a growing lack of empathy shown by the British, Europeans and Americans towards the most visible and vocal members of this community. As they have become more noticeable, they have also been more criticised for perceived misdeeds and backward ideas.

This book is not a re-run or an updated version of the portrait I attempted in 1976, though it does share the same insistence on the necessity of looking beyond daily headlines and instantaneous reactions. The difference is that what follows is a greater concentration on the dominant political creed shared by most Protestants within Northern Ireland. This is unionism: the support for the union between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. But this definition is insufficient: the nature and motivations of Northern Ireland unionism, and indeed British unionism, require further elaboration.

This is much more necessary now than it was even a decade ago, because British unionism in general and its Northern Irish variant have become more interrogated and less confident. Thus, it is contemporary dilemmas and predicaments that inform what follows, albeit while acknowledging that these have important historical roots: in Ireland there is no border between past and present politics. Historically, unionists in the north-east of the island have enjoyed marching, either in protest or in celebration: what this book asks is where they are now marching towards. It is a question many in that community are also asking, today more frequently than ever before.

The superficiality of judgement that too many observers have recently offered is actively unhelpful. Chapter 1 reflects on such verdicts, locating them in their time and political circumstances. It also traces how an optimism and sense of self-importance within Northern Irish unionism, as represented by the Democratic Unionist Party of Arlene Foster when it allied itself to the British Conservatives under Theresa May, ended in disillusionment and resentment as well as ill fortune for the individual leaders concerned.

Chapters 2 and 3 offer some historical context that seeks a contemporary relevance by beginning with more general issues being addressed today in Britain and Northern Ireland. These are notions of exceptionalism and supremacism. In Britain, discussions on these have focused on the legacy of imperialism and colonialism. The context in respect to Ireland is assertions by unionists that the British were intellectually and morally superior to the Irish, and that Irish Protestants were similarly superior to Irish Catholics. Such thinking, I suggest, was a major part of the justification for northern Protestants ideological and physical resistance to Irish self-determination in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For example, the willingness of English Tories at the start of the twentieth century to threaten civil war in support of Ulster remaining British will be explored, as it should be whenever responsibilities for Irelands troubles of whatever generation are discussed.

The propaganda and self-justification for such behaviour has contemporary parallels with the growth of English nationalism and imperialist nostalgia, evident then and in the England of recent times. Accordingly, the continuation of the colonial mentality in Britains approach towards Northern Ireland of today is a theme that will recur throughout the book.

Chapter 4 explores how the alliance between the British and Ulster unionist parties began to fall apart under the pressure of the challenges to their Northern Ireland from the 1960s onwards. The sense of estrangement that developed was particularly manifested within the Northern Irish Protestant community in its growing hostility towards their one-time Tory allies across the Irish Sea. This disenchantment, which was often reciprocated, remains profound and consequential.

Chapter 5 explores one of the effects of that estrangement: that is, how the unionist monolith that had enjoyed more than fifty years of one-party governance in Northern Ireland began to splinter and fall apart and how and why Ian Paisley emerged from the sectarian shadows to become the most successful unionist politician of the past fifty years.