This book was Michael OBriens idea, and de n Laoghaire of The OBrien Press it was who finally persuaded me to write it. I owe them both a debt of gratitude. I loved actually writing the book and I feel that my father and mother and all the people from whom I came will be glad to have been remembered. My editor at The OBrien Press, Rachel Pierce, turned what might have become a drudgery into a series of wonderfully refreshing social encounters without ever relaxing her perceptive efficiency. Thank you, Rachel.

As with all my literary undertakings for many years now, I could never have coped with the archival research involved without the constant, unstinting help of Mire Mhac Conghal, my dear friend who is also a professional genealogist Tim faoi chomaoin agat choche, a Mhire. I also owe a debt to Manus ORiordan for correcting a serious error about Mrs Muriel MacSwiney.

My special thanks to Conor and the children and grandchildren who, in spite of their anxieties about the terrible things I might say, were endlessly loving and supportive. Many other dear friends are thanked in the course of the text.

Most importantly of all, may I thank the Military Archives staff at Cathal Brugha Barracks not only for facilitating my access to material about my mother, Margaret Browne, but also for their undisguised pleasure at the prospect of her plucky and picturesque career, from 1916 to the Truce in 1922, entering the public domain.

An American historian, Wright Morris, is credited with the dictum: Anything processed by memory is fiction. Judged by that criterion, this narrative of mine is doubly fictitious, having been processed not only by my own memories but also by those of my parents generation, on which I have drawn heavily in the important early episodes of this book. Paradoxically, I could claim that fictions can often be a better key to the understanding of actuality than strictly factual accounts. Be that as it may, I have made scrupulous efforts to prune these anecdotes of any conscious fictionalising and am in a position to declare that, as they stand, they are an honest attempt to set down my personal take on the world that was Ireland in the last century.

I find, now that I have formulated my impressions and got them down on paper, I have become oddly detached from them, almost as if I had written a novel. It has been a cathartic experience. Old sorrows have surfaced and then ebbed; old joys have been articulated and have somehow lost their radiance; old animosities seem childish, or unworthy; only old affections remain constant.

This is not a textbook history of twentieth-century Ireland; it is a series of recollections and reminiscences, of personal experiences and of narratives recalled . It partakes of the nature of a stream of consciousness, and where I have reached conclusions the reader is not obliged to agree with them. I offer it as an aid to the understanding of our recent past, always the most difficult period of history to come to terms with. I hope it may also entertain.

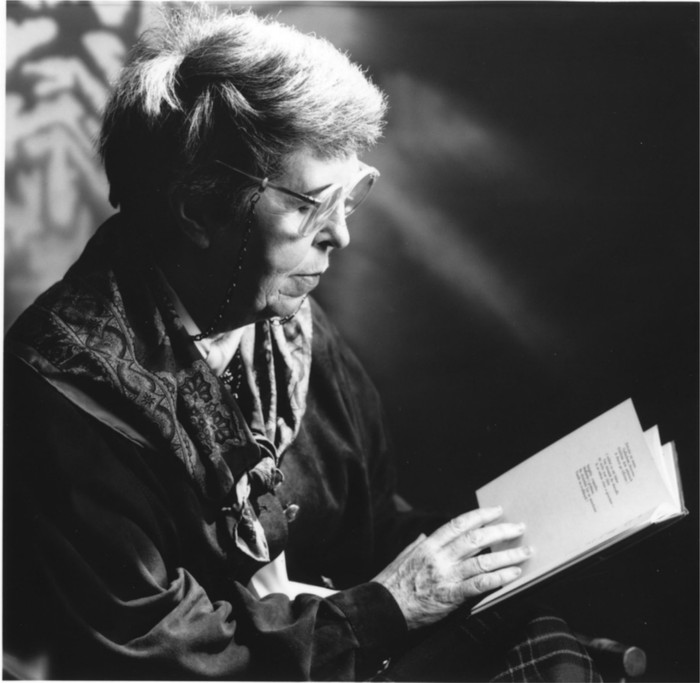

Mire Cruise OBrien

Dublin, 2003

PART I: MY MOTHERS PEOPLE

My maternal grandmother, Kate Browne, died at the age of sixty-five, on 3 June 1923; I remember her from the waist down. We went together to feed the hens in the yard at the back of her house in the village of Grangemockler, County Tipperary, at the foot of Slievenamon in the Decies. They were very terrible hens, and I can remember looking at them, transfixed with fear, over a width of her skirt. God rest her! Her story has been part of my consciousness from the beginning.

Kate Browne was born FitzGerald; the name is common throughout the old Desmond palatinate. Her brother, the Boss FitzGerald of Balladuggan , was a strong farmer in the neighbourhood. The family had not always been so prosperous; in the Hungry Forties (the Famine times) they had been evicted. My mother told me that, of a very long-tailed ( numerous ) family, those born before the eviction were illiterate, Irish-speaking and did well in life; those born after they had resettled, this time in Balladuggan, were educated, English-speaking and never made any money. Presumably the Father FitzGerald who was chaplain to Charles Gavan Duffy in Australia belonged to the second clutch, as did my grandmother , or perhaps he was a clerical uncle from an earlier world.

Together with the sister nearest her in age, Kate FitzGerald was sent to board at the Loreto Convent in Kilkenny, where, as well as getting the sound secondary education of the period, she learnt many ladylike accomplishments . I still cherish a fire-screen worked by her with a bird- of-paradise in crewel, and two gilt-framed watercolours one by her sister, of Kilkenny Castle, and one a copy, by Kate herself, of Constables Old Mill.

My mother remembered being sent on her bicycle, many years later, by her mother to visit a neighbouring parish priest and borrow (or return) the latest novel by Balzac, in the original French. With the innocent intellectual snobbery of the adolescent, she marvelled that French had been taught so well at the convent in Kilkenny. It was only after my grandmothers death that her family learnt that she and her sister had both been novices in the Loreto Convent in Gibraltar, and that she not only read French with ease but also Spanish. The convents records, about which I enquired, do not show that the girls were intended to be choir sisters; perhaps they were lay pupil-teachers, or, even more lowly, lay sisters. (Lay sisters were servants, not professed nuns.) The family tradition says novices and the passion for Balzac is well attested. My poor young great-aunt fell ill and died, and my grandmothers vocation did not survive her death. Kate FitzGerald returned to Balladuggan in the late 1870s to care for her ageing mother and to become, when her mother also died, the unpaid domestic of her brothers, the remaining family. That is my mothers version of the story; my Uncle Moss, in his thinly disguised record of the family, The Big Sycamore, gives a somewhat different one, but the essentials are the same.

Obviously, since, when I knew her, she was a matriarch in her own right and no longer lived in Balladuggan, Kates then situation was not fated to continue. My grandfather, Maurice Browne, was the schoolmaster in Grangemockler, the neighbouring townland. I never knew him. The photograph I have of him,with a greying full beard, was the only one he ever had taken in his entire life. He was born in County Waterford, in Cappoquin, in 1844, the eighth and youngest child of a cooper in a prosperous way of business; the family employed as many as eighty seasonal labourers, men, women and children, when times were good. His parents, feeling that with their last little one they could relax a little from the grim grind of daily necessity, destined him for the priesthood and planned ahead for his education. His first language was Irish, and although my grandmother, mindful of her gentility (a legacy of the convent), always maintained that she had not spoken Irish from the cradle, but picked some up from the neighbours, the pair sometimes spoke it to each other in a, surely vain, attempt to keep something from five avidly curious children. Irish was not at that time a middle-class language; later the Revival would render it fashionable.