THE POLITICS OF CHILDHOOD IN COLD WAR AMERICA

THE POLITICS OF CHILDHOOD IN COLD WAR AMERICA

BY

Ann Marie Kordas

First published 2013 by Pickering & Chatto (Publishers) Limited

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Taylor & Francis 2013

Ann Marie Kordas 2013

To the best of the Publishers knowledge every effort has been made to contact relevant copyright holders and to clear any relevant copyright issues. Any omissions that come to their attention will be remedied in future editions.

All rights reserved, including those of translation into foreign languages. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice :

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Kordas, Ann Marie.

The politics of childhood in Cold War America.

1. Children United States Social conditions 20th century. 2. Teenagers United States Social conditions 20th century. 3. Cold War Influence. 4. Cold War Social aspects United States. 5. United States Social conditions 1945 I. Title

305.23097309045-dc23

ISBN-13: 978-1-84893-285-2 (hbk)

Typeset by Pickering & Chatto (Publishers) Limited

CONTENTS

Completing this manuscript has been a long and difficult process. I would like to thank those who assisted me along the way. I would first like to thank Stanley Lemons and the late George Kellner for encouraging me to develop an interest in the social and cultural aspects of American history. The members of my dissertation committee provided me with invaluable advice as did my first dissertation adviser, Margaret Marsh. The librarians at the Temple University Library and the Philadelphia Public Library also assisted me greatly in locating many of the sources needed to complete this project. Leslie Schuster and Joanne Schneider gave me the opportunity to study the subject of this book in greater depth by allowing me to develop and teach a course in the history of childhood and adolescence at Rhode Island College. Colleen Vasconcellos and Jennifer Helgren helped me to clarify my ideas regarding the use of childhood as a political tool during the Cold War. My colleagues at Johnson and Wales University have provided invaluable encouragement and emotional support, and I would especially like to thank Wendy Wagner, Terry Novak, Mare Davis and Eileen Medeiros for reading portions of the manuscript at our Research Roundtable. I would also like to thank Laura Gabiger for supplying me with muffins, oranges and companionship on the Saturdays and Sundays I spent writing in my office. Colleen Less and Maureen Farrell kept me well-caffeinated throughout the writing process, and Joe Delaney, Nelson Guertin and Fred Pasquariello provided me with much appreciated libations of a different sort. Finally, I would like to thank Toby, Gertie and Alice for their love and companionship and Richard Lamon for not only reading my manuscript but also cooking, cleaning and doing laundry while I worked on this and several other projects.

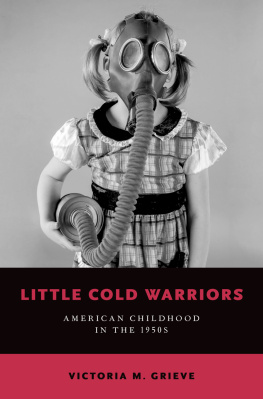

1 May 1950 was a bad day for the children of Mosinee, Wisconsin. Awakening to the discovery that their town had been taken over by communists acting in league with the Soviet Union, high school students rose from their beds to learn that they were required to report to school. Once there, the teens were coerced into forming a Young Communists League and forced to listen to a lecture by former general secretary of the US Communist Party Ben Gitlow, who warned them that family bonds were secondary to the needs of the Party. The students then watched in horror as the high schools football coach was arrested by communist police and dragged off the athletic field. The school band then struck up a sprightly tune and set off on a march to Red Square (the newly rechristened town square). Five hundred people, both adults and children, followed the band while brandishing signs proclaiming allegiance to Stalin and denouncing religion. Those who did not act as they were expected to were sharply rebuked. Little boy, bow to the red flag!, Chief Commissar Joseph Kornfeder, a Czech immigrant and graduate of Lenin University, barked at a puzzled child. Perhaps the cruellest blow to the children of Mosinee, however, was their discovery that candy would henceforth be available only to Communist Youth members, and they would have to learn to subsist on the same bland diet of potato soup and black bread as the adults.

Children were undoubtedly bewildered and frightened during the two-day period in which the American Legion, guided by former members of the Communist Party like Gitlow and Kornfeder and acting with the assistance of Mosinees mayor, police chief and most respected citizens, staged a communist takeover of the small Wisconsin town. The mock invasion had been planned to remind Americans of the threat posed by the Soviet Union and to provide them with a supposed taste of what real life was like for people who lived behind the Iron Curtain. The perverse pageantry that took place on those two spring days in Mosinee, Wisconsin, was only one of many attempts by Americas civic leaders to warn their fellow citizens of the dangers of communism. Such instruction, like most during the Cold War, was aimed not only at adults but at children as well.

During the Cold War era, American childhood was highly politicized. In the period following World War II, American adults quickly realized that the conflict with the Soviet Union, while it did include wars fought primarily by proxy armies at a safe distance from the national borders of either nation, would not be a shooting war. This war, unlike others the two nations had fought, would be one based largely on ideology and on the ability of that ideology to secure allies (and access to natural resources and markets) in third world nations. Victory would come when one of the great superpowers either annihilated the other through the deployment of nuclear weapons or (considered the more likely alternative by the late 1960s) had outdone the other in spreading its political beliefs, its economic system and its culture to a larger portion of the worlds people than the other. Success in the Cold War would therefore be dependent upon the production of patriotic, ideologically sound citizens at home.

Like other nations born of revolution or deliberately created to conform to the dictates of an ideology, the United States had always taken seriously the task of teaching children what it meant to be American and why their nation was superior to all others. However, this mission took on added importance in the decades immediately following World War II. As tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union swiftly grew in the post-war period, Americans found themselves poised for potential battle with a nation whose fundamental beliefs and values clashed with their own. The Cold War face-off between the US and the USSR was different in many crucial ways, however, from previous conflicts in which the US had been involved.

Before World War II and the Cold War, Americans had never found themselves enmeshed in a conflict that was so thoroughly ideological in nature, one based almost entirely upon a clash between profoundly different values and beliefs. The American Revolution, while strongly rooted in republican ideology on the colonial side, was not essentially a conflict with fundamental British political thought. Indeed, many of the writers from whom the nations founders drew inspiration and upon whose ideas they had based their own political thinking were British. The American concern for protecting liberty and curbing the actions of tyrants came from their reading of John Locke. Other British citizens, including many living in England, held the same values. Liberty was an important British value as well as an American one. The resulting conflict was thus not the result of a profound difference of opinion over what rights citizens possessed or what principles a legitimate government should be based upon. It was, instead, a disagreement over which British citizens were the true upholders of these values, those in England or those in North America. It was a rebellion against a government that Englishmen in several of the mother countrys colonies believed was not adhering to agreed-upon political principles, nor respecting peoples fundamental rights.