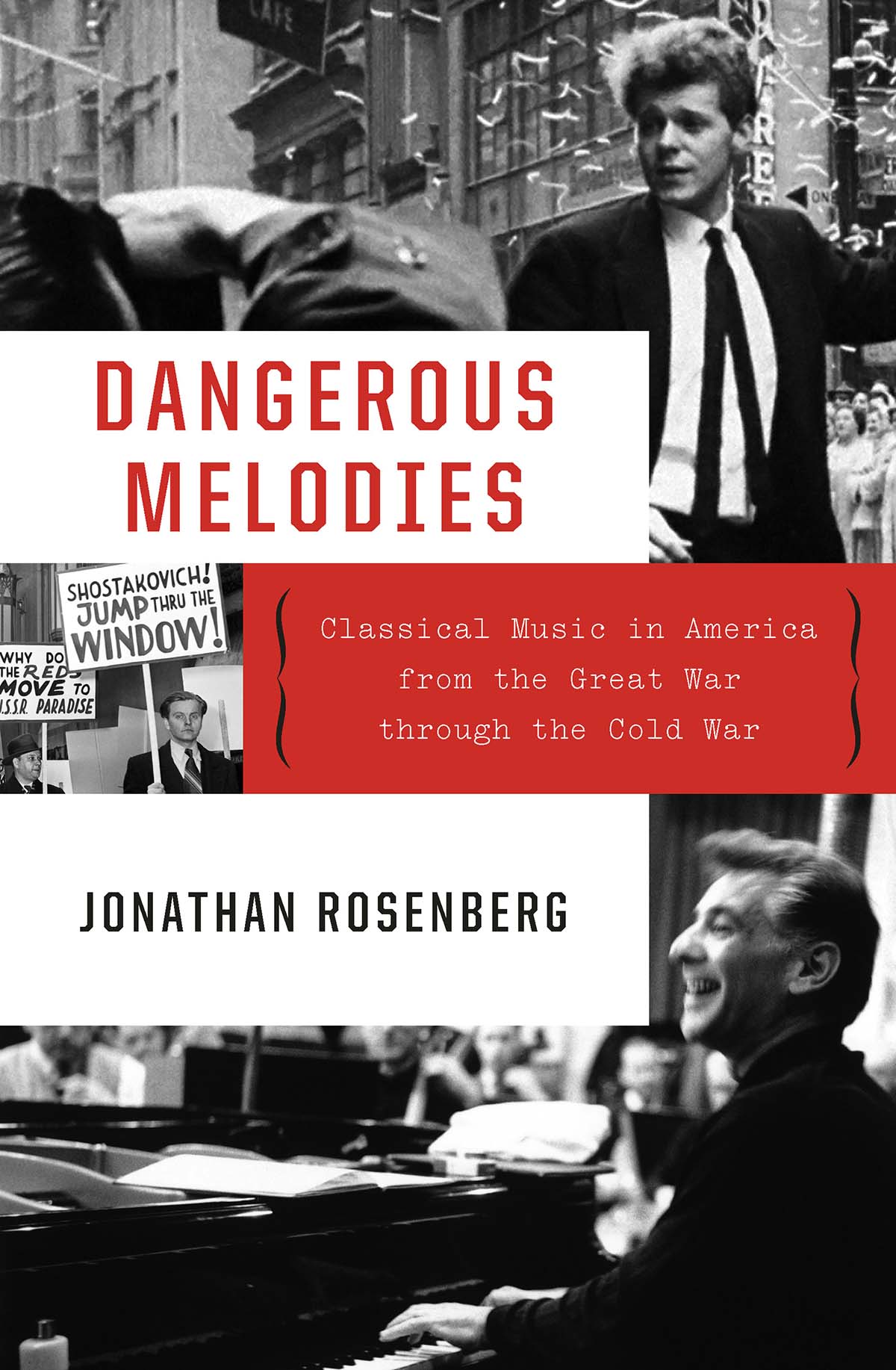

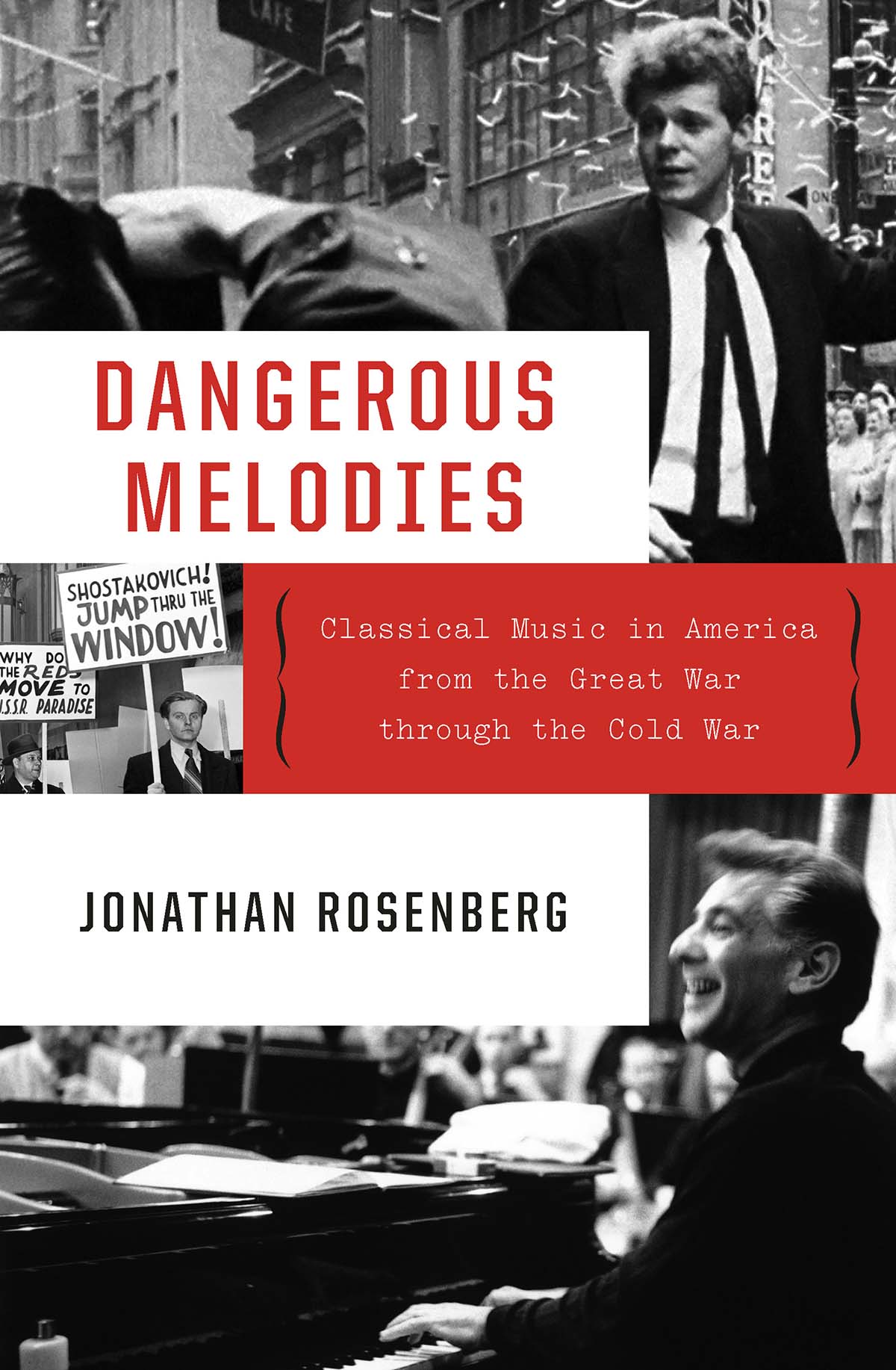

DANGEROUS

MELODIES

CLASSICAL MUSIC IN AMERICA FROM

THE GREAT WAR THROUGH THE COLD WAR

THE GREAT WAR THROUGH THE COLD WAR

JONATHAN ROSENBERG

W.W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers since 1923

For Jane, James, and Isobel

In Moscow, a few weeks earlier, Premier Nikita Khrushchev had been a buoyant participant in the Cliburn affair, and millions of Americans read about the way he had playfully chatted with the young musician at a Kremlin party. The Soviet leader had even given the American a bear hug. For several weeks, the pianists achievement commanded widespread coverage across the United States, starting with news reports in April about his triumph in Moscow, where he captured the hearts of Russian men and women.

Can one imagine such a scenario today? Would the overseas accomplishments of a classical musician capture the attention of Americas political leaders or the countrys newspapers and magazines? Would a ticker tape parade attracting one hundred thousand delirious fans be held for an artist with a gift for playing Tchaikovsky? Clearly, the answer is no. But in an earlier time, a pianists triumph could mesmerize the American peopleand not just classical-music devotees, but political leaders, journalists, and ordinary city dwellers.

Few would question the notion that classical music has little relevance in contemporary America. Its connection to the larger culture is tenuous, and the average adult, even if well educated, has scant interest in the activities of performers, composers, symphony orchestras, and opera companies. The vast majority of urban residents would be hard-pressed to identify the conductor of their local ensemble, and across America, few people can name even one famous classical musician. Leading magazines offer almost no coverage of the goings-on in classical music, and newspapers supply little more than short reviews. For nearly all Americans, the classical-music landscape in the United Statesthe performances by orchestras and opera companies, and the work of singers, instrumentalists, conductors, and composersis alien terrain.

But this was not always so. This book tells the story of a different time, of an age when classical music occupied a prominent place not only in the nations cultural life, but in its political life, as well. To tell that story, Dangerous Melodies explores the interconnection between the world of classical music in the United States and some of the crucial international developments of the twentieth century: World War I, the emergence of fascism in Europe, World War II, and the Cold War. As we shall see, over the course of several decades, classical music was genuinely consequential in America, achieving a position of considerable significance, which the music had never known before and which it surely lacks today. And that was so, in no small measure, because the domain of classical music became entangled in momentous events across the globe.

For now, I offer a couple of snapshots to suggest the extent to which classical music once commanded Americas attention. In July 1942, not long after the United States entered World War II, the American premiere of Dmitri Shostakovichs Seventh Symphony captured the countrys imagination. Arturo Toscanini, the conductor of the NBC Symphony Orchestra, was chosen to lead the premiere of the Seventh, part of which the Russian composer had completed in Leningrad as German troops besieged the city. The broadcast performance, covered extensively in the press, was heard by millions of Americans, who were exhorted to tune in and listen, in a nationwide act of patriotism that the US government believed would fortify the wartime alliance between Washington and Moscow.

But the story of classical musics importance was not always inspiring, for there was a sinister side to the musics place in American life. At times, symphony and opera administrators, responding to an outcry from the public, banned dangerous melodies from the concert hall or the opera house. Equally disturbing, scorn often rained down on enemy singers, conductors, and instrumentalists, who learned they were not welcome to perform in the United States. Some were fired or imprisoned, and a few were forced to leave the country.

Soon after America went to war in 1917, for example, fear and fury exploded across the United States as thousands of people of German ancestry, especially those without American citizenship, became the object of hostility. All things German, whether German language classes, books, or the sale of barroom pretzels, were banned. The performance of German compositions, especially by Wagner and Richard Strauss, caused a ferocious reaction. The concert hall and the opera house became a minefield, and German musicians faced unbridled animosity from a public unwilling to allow enemy artists to perform. During the Great War, many Americans looked upon Germans as demons, whether they were fighting on European battlefields, singing in Americas opera houses, or conducting the nations symphony orchestras. And in decades to come, the appearance of numerous foreign musicians could unleash hatred, arouse fear, or engender angry protest.

The Cliburn triumph, the Shostakovich premiere, the wartime plight of German music and musicians: These are but a few of the stories that point to a time when classical music could pull thousands onto the streets in celebration, compel millions to listen to a wartime broadcast, or induce countless devoted concertgoers and ordinary citizens to reject dangerous melodies.

But why did classical music once command such attention and how to explain its centrality in American life? What caused the world of classical music in America to become so politicized and why did the activities of musicians and performing institutions in the United States become enmeshed in the epochal events of the twentieth century?

As the pages that follow make clear, from World War I through the Cold War, the classical-music community in the United States became entangled in international affairsin the two world wars the United States fought against Germany (with the Soviet Union a crucial American ally and Italy a foe in World War II), in the emergence of Italian and German fascism between the wars, and in the protracted struggle America waged against the Soviet Union after 1945. These three countriesGermany, Italy, and the Soviet Unionwere wellsprings of rich musical traditions and the birthplaces of distinguished musical figures, and Americans had long admired those traditions and the musicians who embodied them. It was difficult, therefore, for people in the United States to separate Americas relations with Germany, Italy, and the Soviet Union from the music and musicians of those three lands. Consequently, over several decades, the classical-music community in the United States was drawn into the swirl of international politics, and the nexus between that community and momentous events overseas supplied classical music with a degree of political significance that is now difficult to comprehend. That convergencebetween the world of classical music in the United States and developments abroadhelps to explain why, for some fifty years, the music occupied a critical place in American life.

By suggesting that classical music achieved an unprecedented degree of political significance during these years, I must emphasize that my aim is not to diminish the profound impact classical music has long had on those drawn to it, whether their passion for music was expressed through performing or through listening. Indeed, having spent a number of years in the music worldpracticing, rehearsing, performing, studying, and teachingI am acutely aware of classical musics capacity to enrich, enliven, and make life infinitely more meaningful for those who regard music as essential to a fulfilling existence. My contention about the significance of classical music in America is, instead, an assertion that in the life of the nation, in the cultural sphereand, more than that, in the political spherethe convergence of the world of classical music in the United States with developments in the wider world supplied the music with a degree of importance that was unlike anything the American people had known.

Next page

THE GREAT WAR THROUGH THE COLD WAR

THE GREAT WAR THROUGH THE COLD WAR