Published by For Beginners LLC

155 Main Street, Suite 211

Danbury, CT 06810 USA

www.forbeginnersbooks.com

Text: 2014 R. Ryan Endris

Illustrations: 2014 Joe Lee

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Design and composition by Tim E. Ogline / Ogline Design

A For Beginners Documentary Comic Book

Cataloging-in-Publication information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN # 978-1-939994-27-1 Trade

Manufactured in the United States of America

For Beginners and Beginners Documentary Comic Books are published by For Beginners LLC.

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

www.redwheelweiser.com

www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter

Contents

Preface

T he History of Classical Music For Beginners was the brain-child of illustrator Joe Lee and me. My dear friend Joe and I met while I was studying and working in Bloomington, Ind. Before I moved to New York to teach on the music faculty at Colgate University, we began talking about a niche that needed filling. Joe has written and illustrated many books in the For Beginners series, and we both felt that the series needed a book about the history of the music we commonly call classical music. I am extremely grateful to Joe for agreeing to team up with me in the making of this book.

The History of Classical Music For Beginners provides the necessary scholarly muscle to entice and inform the reader, yet it does not require an understanding of music theory or force the reader to wade through hundreds of pages of jargon and details. Anyone can pick up this book and instantly start learning aboutand understandingclassical music. Music theory, the study of how music is written and the fundamental elements of music, is excluded from the discussion of music to the greatest extent possible, so that one can read and understand without prior musical knowledge. The use of jargon and terminology has been kept to a minimum; in instances where it is necessary, a straightforward explanation is provided both in the prose and in the glossary. The words are both italicized and bolded the first time they are presented to draw the reader's attention to them.

Covering fifteen hundred years of music history is no easy task. Doing so in the span of a couple hundred pages is even more difficult, necessitating the exclusion of some musical styles and composers. You will notice that even some notable composers (like Tchaikovsky) are absent from this book. The aim of this book is to cover those musical styles and composers who exerted the greatest influence in the history of classical music to give the reader the greatest overall understanding of classical music possible. For example, opera is a genre of classical music that has an entire history of its own, and thus is discussed in only one chapter as part of a larger discussion of stylistic developments. Those wanting to know more about opera in music history should read The History of Opera For Beginners by Ron David. In fact, I encourage you to read and discover more about any composer, music, or topic that especially piques your interest while reading this book!

R. Ryan Endris

Hamilton, New York

March 2014

Chapter 1

ANCIENT MUSIC AND PHILOSOPHY

M any people think of the music of Palestrina, Bach, and Mozart as old music, but the earliest known instruments date to before 36,000 B.C.E.! Today, society considers music as part of the arts, but the ancient Greeks viewed it as part of the sciences. In fact, music was considered as important of a subject as astronomy, rhetoric, and math, and it was often taught alongside those other subjects. The music of ancient Greece (ca. 500 B.C.E.) focused on the role of numbers and mathematics in music. For example, Pythagoras used simple mathematical ratios to define consonances in music of the perfect fourth (4:3), perfect fifth (3:2), and perfect octave (2:1), which are still considered and labeled perfect sonorities to this day. He discovered that when a string is divided into segments with ratios of those lengths, those are the sonorities that sound.

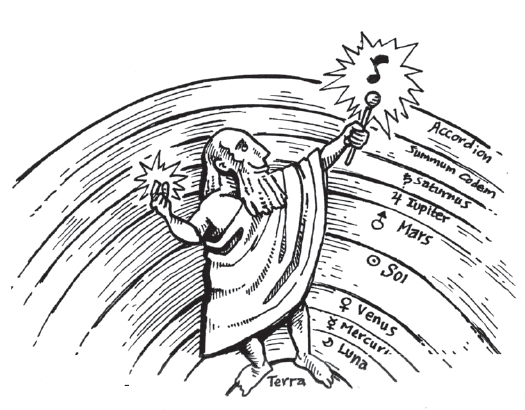

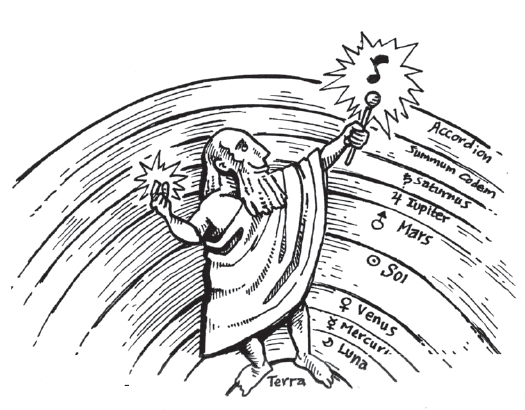

Pythagoras proposed the theory of musica universalis, or music of the spheres, the theory that the planets, sun, and moon all produce a sound or hum based on their orbits. The sounds produced by the celestial bodies, while inaudible and imperceptible to humans, indeed had an effect on the quality of life of the inhabitants of the earth. In his book The Republic, Plato also proposed that the study of music and astronomy were linked by mathematics and numerical proportions. Because numbers inherently governed musical rhythms and sound, music was reflective of the unification of parts in an orderly whole. In this way, music was a prime example of an order that could be sought in other areas, such as philosophy or the structure of societies.

Early Greek writers believed that music could affect one's ethos, or way of being and behaving. Aristotle wrote of this in his Politics: music of a particular emotion or feeling was capable of evoking that same emotion or feeling in the listener. This idea is rooted in the Pythagorean view of music as a system of pitch and rhythm associated with the same mathematical laws that governed the visible and invisible world. They believed that the human soul was comprised of parts kept in harmony by these orderly systems, and thus music had the potential of infiltrating the human soul. Both Plato and Aristotle held the idea that music was on equal footing with gymnastics in one's education. Gymnastics were intended to provide discipline for the body, while music was to provide discipline for the mind.

Even though this might sound silly to one at first, this idea of the ethos of music has had staying power. Even into the Baroque period, composers still prescribed to the doctrine of affections, a belief that emotions such as sadness, joy, anger, love, wonder, and excitement were states of being in the soul, and each one was caused by spirits, or humors, in the body. Music at this time did not seek to express the composer's personal feelings, but rather sought to portray affections generically.

Next page