I am grateful to the editors at Prometheus Books, to my agent, Barry Zucker, and to the many editors who have taught and guided me along the way, including Chad Rubel; Mark Karlin; Meg White; Alex Cockburn; Jeffrey St. Clair; Kim Petersen; Sunil K. Sharma; Angie Tibbs; Selwyn Manning; David McLellan; George McLellan; Rob Kall; John Roberts; Pascale Fusshoeller; John McEvoy; Daniel Ballarin, MD; Alan Gray; Judyth Piazza; Tom Williams; Don Hazen; Tana Ganeva; Tara Lohan; Liliana Segura; Adele Stan; Bev Conover; Craig Brown; Jon Queally; William Franklin McCoy, MD; Stephan Gregory; Diana Mathias; Maureen Zebian; Christine Lin; Stephanie Lam; Dan Wilson; Barry Sussman; Lydia Sargent; Robert Whitcomb; Lois Kazakoff; Nicholas Goldberg; Nick King; Marshall Froker; Colin McMahon; Sidney Wolfe, MD; Gregg Runburg; Karen Sorensen; Mark Law; Sherren Leigh; and especially Mary Helt Gavin, editor and publisher of the Evanston RoundTable.

I am indebted to the research support of Samantha Martin, Dianna Stirpe, and Patrick Sugrue, the librarians at Northwestern University, University of Illinois at Chicago, Rush University, and the Evanston Public and Harold Washington Libraries, and to my brilliant pharmacology professors, whom I sometimes actually understood.

I also greatly appreciate the consumers, patients, clinicians, and researchers who've written me; the activists working in animal welfare and drug safety; and my steadfast friends at Quartet and the North Shore Club.

Finally, thank you to my mother, father, Kristin, and Sue; my second family, Doug, Annie, Floyd, and Maria, and to John Hughes and John Keyser Tice, PhD, who still light my path.

C an anyone remember life before Ask Your Doctor ads?

All you knew about prescription drugs came from the ads you peeked at in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in your doctor's waiting room. They were full of vaguely ominous termsnulligravida? hemodialysis?as well as side effects and overdose treatments that you didn't understand and didn't want to understand. And they confirmed that the doctor knew more than you, more than he was telling you (and if this was more than twenty years ago, the doc probably was a he), and sometimes he was looking down on you.

In the 1950s, JAMA ads had a hokey feel to them, with cartoons and ads for soda pop, orthopedic shoes, and sickroom supplies. Fifty million times a day at home, at work or while at play, says an ad, referring to the wide use of what seems to be a medicine but is actually Coca-Cola. Here's why. On the back of the bottle are listed all the ingredients of this sparking, crystal-clear drink. Yes, soft drinks weren't just empty calories!

But by the 1960s, JAMA ads boasted slick, Mad Menstyle ads for the tranquilizers Valium, Librium, and Miltown; the antipsychotics Thorazine and Mellaril; the amphetamine Benzedrine; and antidepressants like Elavil and Triavil. Commensurate with the psychoanalytical times, before biological psychiatry, in which people with emotional problems had shrinks, neuroses, and complexes, many ads suggest patients are motivated by drives and impulses they deny.

Do you have patients who try to hide frustration behind conformity? asks an ad for the antidepressant nortriptyline, depicting a bored, upper-middle-class couple in Burberry-like attire. They may be unable to face the pain of their depression, says the body copy.

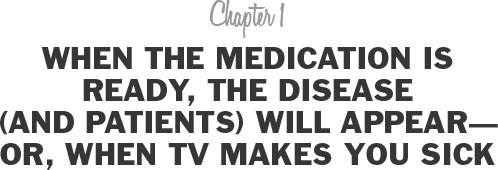

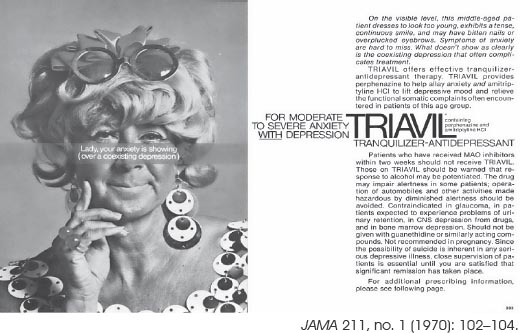

One ad lacquers ageism and sexism onto denial by showing an older, wrinkly woman in a bouffant wig with hair bows, gigantic sunglasses, and garish jewelry.

The headline, Lady, your anxiety is showing (over a coexisting depression), is written across her nose to further the ridicule. On the visible level, this middle-aged patient dresses to look too young, exhibits a tense, continuous smile and may have bitten nails or overplucked eyebrows, says the ad copy. What doesn't show as clearly is the coexisting depression. The ad suggests the antidepressant and tranquilizer Triavil.

A third patient-in-denial ad depicts an upper-middle-class breakfast scene. Under a chandelier, a smiling wife and mother in a flowered housedress has prepared a breakfast of cooked cereal, juice, milk, and percolated coffee (who remembers coffee percolators?) for her executive-type husband and their college co-ed daughter, who is wearing pearls. The headline says, The prehysterectomy patient who wears a faade of unconcern. When you turn the page, the husband and daughter have leftand so has the woman's smile. It's all an act.

Such ads elucidating the pathos of aging wives and mothers who are losing their looks, children, femininity, and purpose in life were rampant in 1960s and 1970s medical journals, before the women's liberation movement had taken hold. One such ad shows a woman at her child's graduation ceremony with the headline Magna cum depression, referring to the empty-nest syndrome she will soon, presumably, experience.

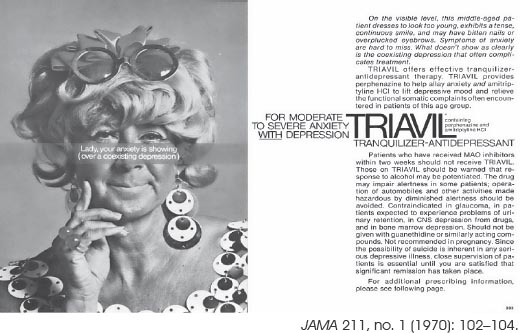

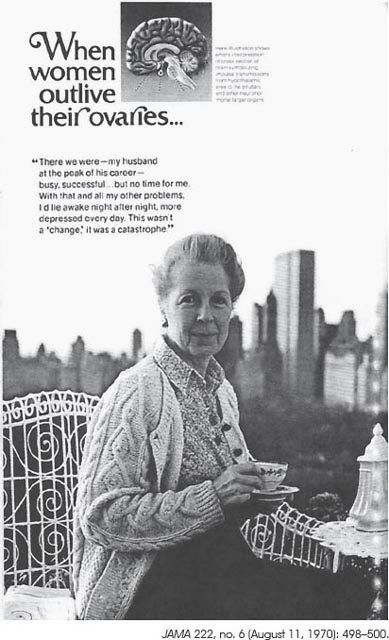

Ads for hormone replacement drugs like Premarin were even more ruthless.

When Women Outlive Their Ovaries is the headline for one, showing a grandmotherly woman in a frumpy cardigan sweater. There we weremy husband at the peak of his careerbut no time for me, says the ad. This wasn't a change, it was a catastrophe.

Journal ads during the 1960s and 1970s also pushed drugs on men, who were having trouble with gender roles. The contemporary businessman, said ads for the antipsychotic Mellaril, is always fearful about his standing with the boss, misses half of what is said at meetings, because he is so emotionally upset, loses his temper with colleagues and subordinates, and goes home at night and takes it out on his family.

Some ads are almost sympathetic to housewives who, before the women's liberation movement, were supposed to find fulfillment taking care of others and their homes, with no job or career of their own. But instead of recommending freedom for women suffering from what early feminist Betty Friedan called the problem that has no name (the problem was suffered by women with material comforts but no intellectual outlet) the ads counseled tranquilizers and other psychiatric drugs. Why is this woman tired? asks the headline under a photo of a dissipated, bathrobe-clad young woman about to tackle a stack of dirty dishes. She may just need more sleep, says the ad, but she also may be one of many of your patientsparticularly housewives[who] are crushed under a load of dull, routine duties that leave them in a state of mental and emotional fatigue. For these patients, you may find Dexedrine an ideal prescription.

I'm restless, nervous, tired all the time and always nagging, says another dirty dishes ad, this one for the antidepressant Sinequan. Another Jan who can't find a husband to measure up to dear, old dad?

Bad wivesespecially nagging wivesmade a regular appearance in drug ads. A sleeping pill for night squawks was the sexist headline for an ad for the hypnotic sedative Doriden, in a 1969 issue of

Next page