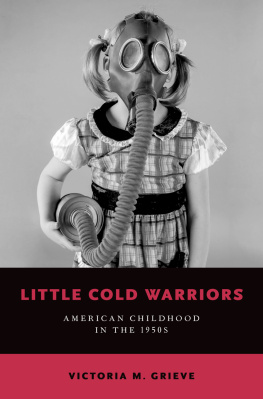

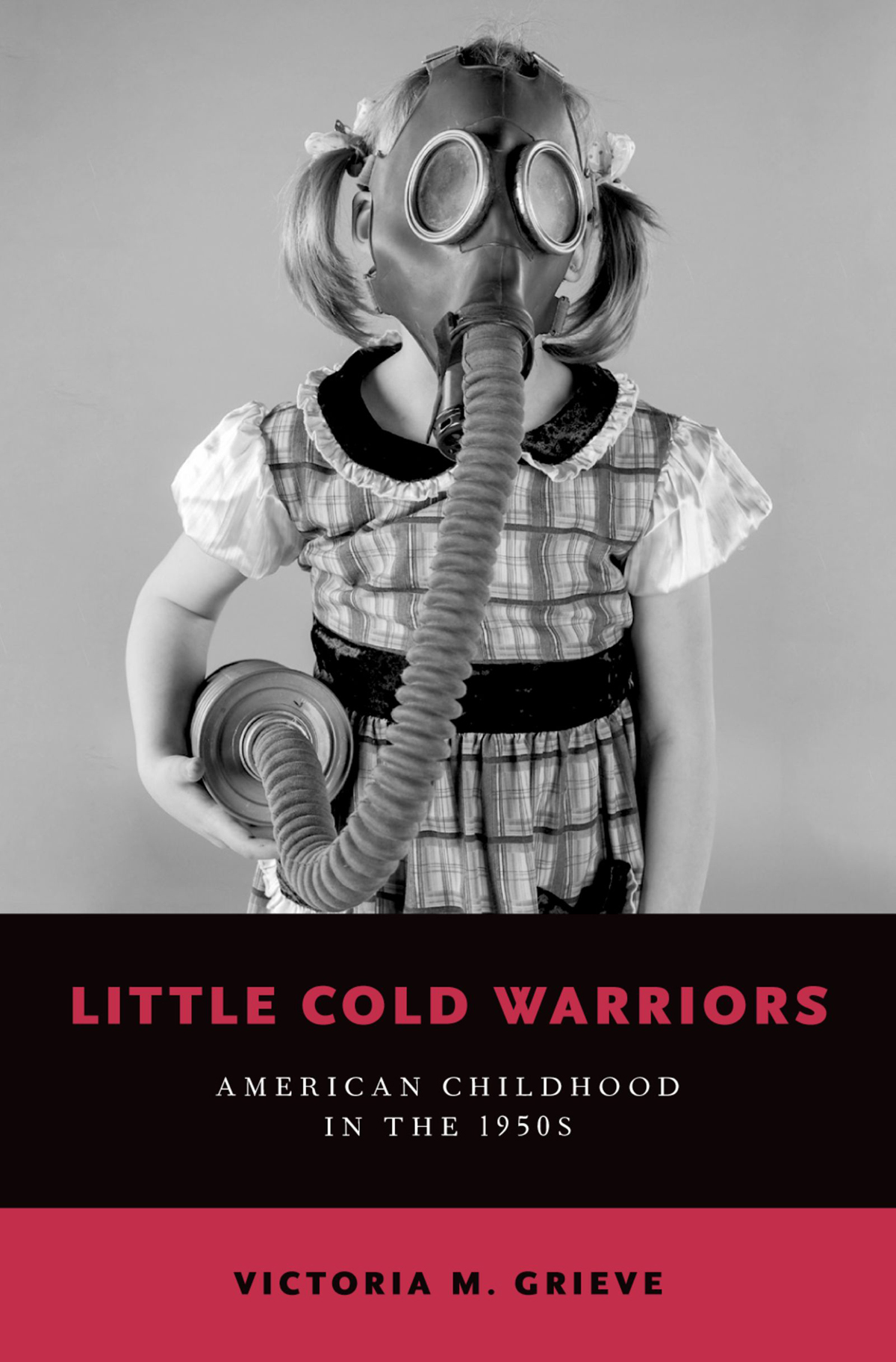

Little Cold Warriors

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Grieve, Victoria, 1972 author.

Title: Little cold warriors : American childhood in the 1950s / Victoria M. Grieve.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017054098 | ISBN 9780190675684 (hardcover : alk. paper) |

ISBN 9780190675707 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Children and warUnited StatesHistory20th century. |

Children in popular cultureUnited StatesHistory20th century. |

Children and politicsUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Propaganda,

AmericanHistory20th century. | Cold WarSocial aspectsUnited States. |

United StatesForeign relations1989Social aspects. |

Cold WarInfluence. | Nineteen fifties.

Classification: LCC HQ784.W3 G75 2018 | DDC 303.6/6083dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017054098

CONTENTS

This book has been a long time in the making, and many people have contributed to it along the way. It is my pleasure to finally acknowledge everyone who helped make it possible.

I presented portions of were presented at the Society for the History of Childhood and Youth. Friends and colleagues provided helpful feedback and suggestions to improve the manuscript at every stage.

Utah State Universitys History Department and the College of Humanities and Social Sciences provided financial support for research and travel. Endless encouragement and many lunchtime conversations with friends and colleagues, especially Daniel McInerney and Tammy Proctor, helped me refine my thinking on several issues in this book. The Friends of the Princeton University Library; Duke Universitys Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History; and the Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum provided travel grants that allowed me to complete archival research. The archivists at these institutions, as well as Marva Felchlin at the Autry Museum of the American West and Wendy Chmielewski and Mary Beth Sigado at the Swarthmore College Peace Collection, were gracious hosts and valuable sources of knowledge and expertise. Thanks also to Marilyn Holt and Dawn Moore for responding to email inquiries and requests for assistance.

Finally, this book would not be in your hands without the constant support of my husband Paul, and my children, Nathan and Naomi, who have inspired me in countless ways over the past 11 years. I hope that they, like many of the young people in this book, recognize the complexity of the world and continue to fight for justice, peace, and true world friendship.

Little Cold Warriors

Duck-and-cover. Leave It to Beaver. Dr. Spock. The Baby Boom. The polio scare. Juvenile delinquency. Is this American childhood and youth in the 1950s? Yesand no.

American childhood in the 1950s is best understood as an era of political mobilization. Although Americans are comfortable with the patriotic history of children helping with the war effort during World War IIsaving their nickels for war bonds, planting Victory Gardens, and collecting rubber and tinwe tend to think of the 1950s as the decade when children returned to being children after decades of depression and war. Both conservative and liberal Baby Boomers have romanticized the 1950s as an age of innocenceof pickup ball games and Howdy Doody, when mom stayed home and the economy boomed. And the drama of the divided Sixties made the Fifties seem even tamer by comparison. These nostalgic narratives obscure many other histories of postwar childhood, one of which has more in common with the war years and the Sixties, when children were mobilized and politicized by the US government, private corporations, and individual adults to fight the Cold War both at home and abroad.

From the late 1940s through the 1960s, all Americans mobilized to wage a global struggle against communist expansion. As they were reminded repeatedly, the fate of Americas children, national survival, and the very future of freedom were at stake. Ideological mobilization occurred in a vast array of public and private spaces, from the White House to the private suburban home, in Congress and in public schools, in the pages of science textbooks and Betty Crocker cookbooks. Over the past decade, historians of American childhood and foreign relations have begun to explore how different groups of Americans, including children, experienced and participated in Cold War politics. But, in popular memory, American childrens experiences continue to be summed up inadequately with easy references to Bert the Turtle and duck and cover, which do little to explain childrens real lives and merely create images of victimized youngsters. In fact, American children actively fought the Cold War on the home front and abroad in many ways. Children watched their heroes battle communism in its various guises on television, in the movies, and in comic books; children themselves practiced safety drills, joined civil preparedness groups, and helped to build and stock bomb shelters in the backyard. Children collected coins for UNICEF, exchanged art with other children around the world, prepared for nuclear war through the Boy and Girl Scouts, raised funds for Radio Free Europe, sent clothing to refugee children, and donated books to restock the diminished library shelves of war-torn Europe. Rather than rationing and saving, Americans were told to spend and consume in order to maintain the engine of American prosperity. In these capacities, American children functioned as ambassadors, cultural diplomats, and representatives of the United States.

The politicization of childhood during the Cold War era was not a new phenomenon. Visual and rhetorical images of children had been used for political purposes by Progressive reformers like Lewis Hine at the turn of the twentieth century to condemn child labor, to justify federal relief programs during the Great Depression, and to mobilize the home front By definition, an inherently neutral child was apolitical; his or her actions could not be construed as political. A politicized child, therefore, was the product of external sociopolitical forces or, as the United States argued in the case of Soviet children, brainwashing and ideological indoctrination. Throughout the Cold War, Americans frequently accused the Soviet Union of brainwashing their youngest citizens to accept and embrace communism while maintaining that American children were free from state-sponsored propaganda.