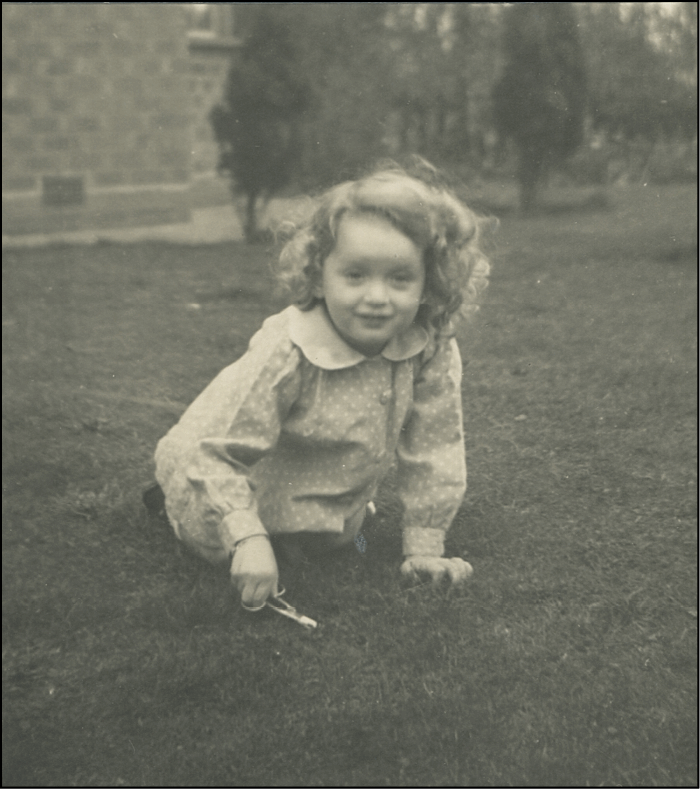

Francis helping to cut the grass

Chapter

Will Father Christmas Know Where I Am?

Frances, born October 1937 in Quinton, a suburb of Birmingham, England.

F rancess parents had been married for just three years and she was only two years old when the war started. The war affected her family early because they lived on the outskirts of Birmingham, a major industrial center with large manufacturing plants for trucks, planes, and other technical goods necessary for defense. Consequently, German bombers targeted Birmingham frequently during World War II.

Frances recalls:

My father was carrying me outside in the middle of the night. Looking up into the darkness, I saw the stars for the first time. I also saw something elsehuge searchlights crisscrossing the sky. Startled and wide-awake, I shivered in the cold. My father had snatched me out of my warm bed because of the air raid alarm and took me to our air raid shelter under the garage.

Outfitted just for us, the shelter had two folding cots for my parents, and a wooden bunk bed with a brown wool tartan blanket as a curtain for me. My mother placed me in my bed, gave me another good night kiss, closed the curtain, and expected me to fall asleep again. Of course, I was not sleepy anymore. Through a gap in the curtain, I saw my parents sitting on their cots. They played cards and drank hot cocoa by the light of an oil lamp that stood on a small table between them. I felt left out of the fun.

There must have been many repetitions of this event. One time, we had an air raid warning on Christmas Eve and my father carried me on his shoulders to the shelter. I worried, Will Father Christmas know where I am. Well, he knew. In the morning I found my long, brown, knitted Christmas stocking. Father Christmas had filled it for me with an apple, nuts, some coins, and a small toy.

Another time I sat on my fathers knees listening to the radio. Sweets will be rationed, the announcer intoned. Fran, did you hear that? my father asked. Yes, I had; and little precocious me jumped off his lap in protest and ran to my mum to share the bad news.

Of course not just sweets, but almost all food was rationed during the war. Everyone had a rationing book and had to register with a local grocer who was provided with enough food for registered customers. The rations curtailed my mothers cooking, although I did not notice it at the time. For instance, at Christmas we had no cookies. How can you bake for the holidays if all you have is one egg, oz. of butter, and oz. of sugar per person/per week for all of your meals? Imported fruit and some deserts were never available. I did not know oranges, lemons, bananas, pineapples or ice cream until I was seven years old or older.

To supplement the limited diet, everyone had a garden or an allotment to grow as much food as possible. They were called Victory Gardens. Ours was not far away from our house. Sometimes when we went there, I was allowed to ride in the wheelbarrow. My parents spent a lot of spare time working in the garden growing vegetables, potatoes, and some berry bushes. I was their helper and had a little plot of my own, where I grew radishes. As they became plump and red, I was eager to eat them, but disappointingly, I did not like their taste at all.

We were fortunate that my father was not drafted into the military, because he worked for CAV Lucas, a company that made auto accessories and other mechanical items needed by the army. Two of my uncles and an older cousin were drafted and served several years without being wounded, imprisoned or killed. I heard that our family was very relieved, when the war ended, and they had survived without harm. Many British soldiers were less fortunate. My parents talked about men that never returned from the war.

The men at home had to work harder during the war. My father left early for work and returned late. I only saw him on weekends. In addition, he was a volunteer fireman. While our house and neighborhood were not destroyed, other sections of Birmingham were. The German Luftwaffe bombers would attack at night, and usually the explosions caused destruction and fires. Then my father was called to duty.

My fathers fire-fighting suit hung by the front door. It was yellow and black, and I knew it was fireproof, so it probably contained asbestos. Next to the suit hung his firemans hat, a loop of rope, and some length of hosepipe. On the floor sat a stirrup pump and a large menacing ax, which I was not allowed to touch and never did.

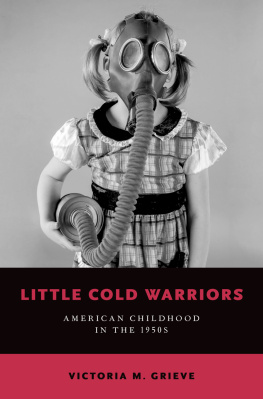

A gasmask was issued to everyone in Britain, including children. My mask was very special. It had black ears, a Mickey Mouse face and when I was breathing through it, the black ears wiggled. My friends thought it was very funny. I looked forward to our war drills in school when we had to wear our masks. But there was a frightening reason for them: to protect us from poisonous gas used by the Germans. Fortunately, this never happened.

When I was three years old, I entered pre-school and when I was five I was already riding the public bus to school on my own, which astonishes me today. Maybe this was normal at the time because everyone used public transportation during the war years.

My father had a car but never got to use it. Petrol was rationed. With his monthly allowance of petrol he had the luxury of driving around our block once. The rest of the time the car sat in our garage.

The war made it almost impossible to import cloth. Most of the material available was used by the military for uniforms and parachutes. We had sixty-six clothing coupons per year, which was equivalent to one complete outfit. Growing children were allowed ten extra coupons. Second-hand and privately sold clothing was not rationed. Evening classes were set up to teach housewives how to make new clothes from old ones.

In addition, my mother studied numerous magazines to learn how to re-trim an old dress, turn a dress or shirt inside out by undoing the seams and re-sewing it, as well as other useful skills.

We had to save water in case the reservoirs were bombed, which fortunately never happened. A line was drawn on the bathtub and you were only to fill the bath to the line.

The British war slogan was: reduce, repair, restore, reuse, and recycle. Nothing was ever wasted.

My sister is five years younger than I. Before my mothers due date, Auntie Pat came to take me by train to my grandparents in Cheshire. All the trains were steam driven and the inside of the stations were black with soot and smoke. Most interesting for me was the black St. Bernard dog that came through the long train corridor with a collection box on his back, collecting money for the St. Bernard orphanage for children.

I stayed with my grandparents for a month, and one day I was called to the telephone and told that my new baby sister had been born. Apparently I said: Call her Susan. And that became her name.

During the war, all houses had to have solid black curtains at every window. They had to be fully drawn at night so that no light could escape, as this would show German bombers where houses and towns were located.