I have to thank the following people for the time they took to tell me their childhood stories and for the help I received in putting this book together: Penny Legg, for all her help and advice that did so much to bring this book to fruition; Joe Legg, Pennys husband, who was there for me and was a huge help in transporting me to 1940s shows; Thomas and Joe Legg, for all of their help with the shows and the photographs of the London Underground; Jim Brown, for the excerpts from his books about policing in the 1940s; Peter and Jax Lovesey, for the wonderful foreword for the book and their fascinating memories of school life; James Reeves, for editing the manuscript; Julie Green, always a big help with photographs of old Southampton; Nigel Smith; Sophia Brothers; Martin Longhurst, for his input about childhood in Portsmouth; Keith and Gloria Tordoff, of the Oldest Sweet Shop in England; Kirsty Shepherd, the Oldest Sweet Shop in England; James Noyce, British Path; Melanie Sambells, Mirrorpix; Simon Murray, London Transport Museum; Anna Renton, London Transport Museum; Joe DCruz, Getty Images; John and Mel Sions and family, for their family photographs taken at Brooklands Museum; C Carte, Tram 57 project, that produced the great photos of trams in Southampton; Dame Vera Lynn, for permission to mention her in the book; Anita Nimmo, for setting this up with Dame Vera my appreciation goes to her for this; Ian Dawson, alias Viv the Spiv, for his help and co-operation; Bill Fowler, The War and Peace Show; The Home Front Bus, War and Peace Show; Eddie Cambers, The Home Front Bus; Ian Bayley, 1940s Society; Rex Cadman, The War and Peace Show; Roger Smoothy, Kent photographic archives; and Lesley Maxim, Romney, Hythe and Dimchurch Railway.

C ONTENTS

One |

Two |

Three |

Four |

Five |

Six |

Seven |

Eight |

Nine |

Ten |

Eleven |

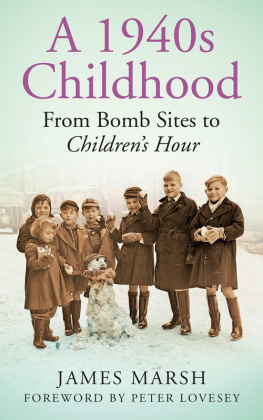

If, like me, you grew up in the 1940s, this book is the nearest thing to a time machine you are likely to experience. The boys-eye view of these formative years awakens memories I hadnt expected to retain. Images from way back have flooded in: hunting for shrapnel after an air raid; eating toast thick with dripping; swatting flies that had somehow escaped the flypapers hanging from the ceiling; and singing Therell always be an England at the riotous Saturday morning pictures. For our parents these were stressful years. Quite apart from the separations caused by war service and the shortages and deprivations, there was the threat of being bombed and invaded. But for most children, the war and its aftermath were opportunities for excitement and adventure. James Marsh perfectly captures this mood. What a good idea it is to view the decade from a childs perspective. I suppose we all tend to remember the positives. After my family was bombed out by a doodlebug in 1944 and we were homeless, I can recall the adventure of being billeted to a Cornish farm at harvest time, followed by the sense of importance it gave me when I eventually returned to my suburban school. I also remember the kindness of the Yankee GIs, who put on a Christmas party at the local base for kids like us. Only much later did I understand the trauma that the bombing must have been for my parents.

Even the enforced austerity of the post-war years didnt drag us down. School dinners were a bad joke we all shared. Our education was often rote learning enforced by the cane, but we had our ways of cheeking the teachers. The onset of smog was a chance to go home early and get lost on the way. Books looked dull and lacked jackets, but what a treat they gave our imaginations. James mentions Richmal Cromptons Just William series, and I am sure my relish for those beautifully written books gave me a grounding in the language that later enabled me to take up writing as a career. But I mustnt be tempted to pick out my favourites its done so much more eloquently in the pages that follow.

Peter Lovesey

When I was asked to write this book it was the answer to something I had wanted to do for some time. I had already published my own story of being born in Southampton in 1940 and growing up there during and after the Second World War, but I quickly realised this was only a small part of the whole story. Great Britain was bombed severely during that conflict, so children across the country went through the same trials and hardships. I knew this and wanted to get this message out if I could. Then came the offer of writing A 1940s Childhood: From Bombsites to Childrens Hour . Now my chance had come to write a childs view of the most devastating decade in this countrys history. I have enjoyed every moment of the time it took me to accomplish this. IA lot of people shared their memories of childhood in the 1940s with me, and this has given me the chance to give the children of Great Britain a voice and show the war from their viewpoint.

One thing shines through it all and that is the fact that kids will be kids, no matter what is happening in the world around them. I hope I have captured that very important point in this book.

James Marsh, 2014

One

September 1940. You should be tucked up warm and snug in your bed. Mum will start shouting for you to get up soon because its a school day. But theres more than one mum shouting this morning. Youre not in your own bed, or even your own home. This is the platform of Piccadilly Circus Underground station, where you were rushed last night because of the air raid that took place before bedtime. Weve had to put up with this sort of thing ever since our Prime Minister, Mr Chamberlain, told the whole country we were at war with Germany. Boys and girls everywhere will remember the broadcast, sitting around the wireless on that Sunday morning:

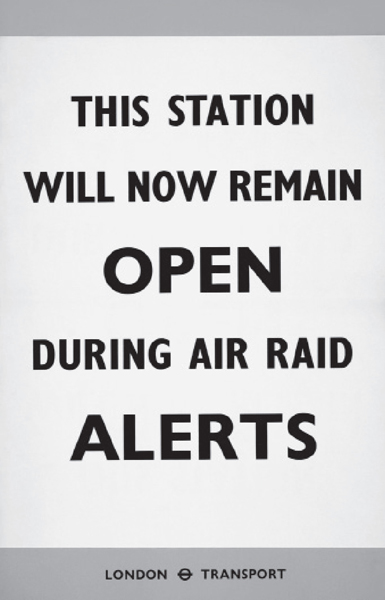

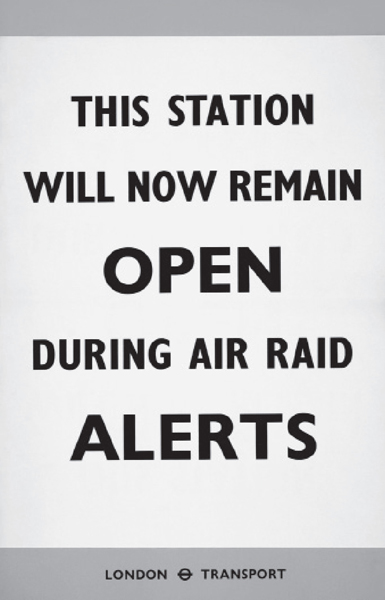

It soon became apparent that the Underground was the safest place for London people to shelter from the constant bombing of the capital. (London Transport Museum)

This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government a final Note stating that, unless we heard from them by 11 oclock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us. I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany.

Children received this news with a mixture of excitement and fear. The world we knew, both school and home life, would change beyond all recognition. Some were already being sent to safer places to get away from the bombing. Towns and cities around our country were supplying gas masks and strangely named things like Anderson shelters. First of all I helped dad. Then he went away, to fight, according to mum, so I helped granddad dig a blooming great hole in the back garden for these to be put up. And for what? Well, ever since that man your mum calls Adolf Hitler started having his aeroplanes drop bombs on us, we need somewhere to get safely away and hopefully stay alive. Here in London most of us rush down to the Underground and spend the night there. Its okay really because theres a lot of fun to be had as you race your mates along the platforms making plane noises. But the grown-ups dont like it and tell us to pipe down all the time. Wheres their sense of adventure?

Next page