Mrs Mary Ashall and Patrick Ashall

David Blackwell and Diana Barbour

George D. Carroll

Henry Lavington and Peter Lavington

Cyril T. Meager and Tom Meager

Maurice Turner

Frederick Galea, Hon. Secretary, National War Museum Association, Malta

John Mizzi, Editor, Malta at War m agazine

Margaret Magnuson, former Librarian, Royal Engineers Library

Joseph Camilleri, Mosta

Antony Spiteri, Mosta

John Firman

Jane Elder

Chris How, Original Artists

Dan Willis

My thoughts were a little incoherent. Suppose this fuze turned out to be a modified pattern? Suppose it contained a booby-trap? All sorts of possible reasons for disaster chased through my mind. But in fact there was nothing to do but follow the directions I had learnt

I now had twenty-five minutes to wait for the condensers to discharge. For that interval I could leave the bomb and the shaft. There was really no reason for staying; indeed, according to the instruction book, I ought to wait elsewhere. But I was trembling and if I rejoined the others theyd notice it

Suppose the bomb should go off while I was here on the opposite side of the shaft? I might be maimed or blinded. It was ridiculous of course. If the 50kg SC had detonated in that confined space there would have been little left of me and I should have known little about it. But the thought persisted, so I went and squatted close to my impassive, cylindrical companion.

Eventually my watch showed that the time was up and I removed the discharger from the fuze. Then, with a spanner, I tried to turn the locking-ring that held the fuze-head. It was tight and would not stir. I stood up and looked down at the bomb; my hands were wet and I felt very scared. After a moment I bent down again, poised myself for the effort, and put everything into it. The ring slackened, and after that turned easily. When it was unscrewed I lifted it away and then removed the locating-ring. Nothing happened. I had half expected something new and devilish would come into operation at this stage, but everything was still going exactly to plan.

I climbed up the shaft and called the Sergeant as casually as I could, telling him to bring the fuze-extractor I went back down the shaft and fixed the extractor to the bomb, screwing its business end into the threads lately occupied by the locking-ring I climbed out and joined him and we both took cover behind a convenient wall he heaved at the cord soon we knew that the fuze must be out of the bomb.

Down I went again, removed the extractor, and unscrewed the gaine from the electrical fuze. The job was done.

A.B. Hartley

CONTENTS

Chapter 1 |

Chapter 2 |

Chapter 3 |

Chapter 4 |

Chapter 5 |

Chapter 6 |

Chapter 7 |

Chapter 8 |

Chapter 9 |

Chapter 10 |

Chapter 11 |

Chapter 12 |

Chapter 13 |

Chapter 14 |

Chapter 15 |

Chapter 16 |

Appendix 1 |

Appendix 2 |

Appendix 3 |

Appendix 4 |

Appendix 5 |

Appendix 6 |

Valletta, the Three Cities and the harbours.

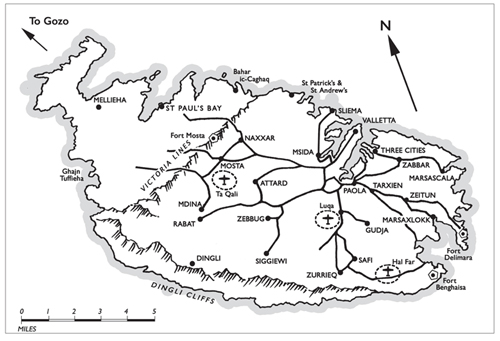

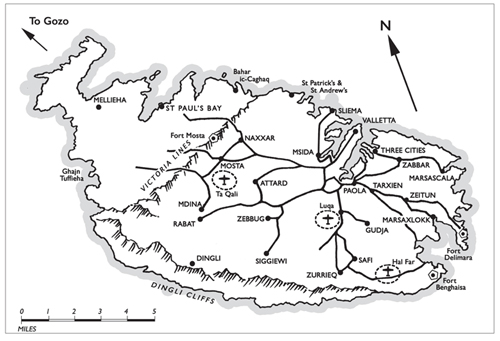

Malta, with key maintained roads, 1943.

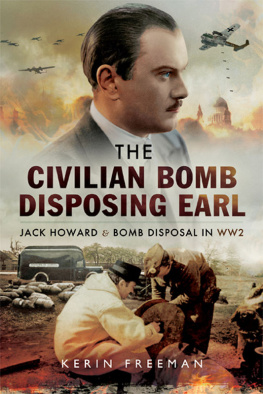

In September 2005 I visited Malta in the company of former RE Bomb Disposal officer Lieutenant George D. Carroll. Like many visitors to the Island, we went to the Rotunda at Mosta to see an exhibition commemorating the events of 9 April 1942, when a Luftwaffe bomb penetrated the great dome of the church during Mass, but did not explode. George Carroll looked up at a photograph on display and said Thats Edward Talbot! Seeing our interest, the gift seller held out a postcard of the same picture, which he said showed the men who removed the unexploded bomb from the Church in 1942. George turned to me. Thats impossible, he said. Edward was dead.

During our stay on the Island, George was interviewed by a local historical organisation and recounted many stories about his wartime service in Malta. However, at the age of 87, his memory was incomplete a phenomenon I have since learned was not uncommon among those who experienced the height of the blitz on Malta in the first months of 1942. Back in the UK, I was surprised to receive an email from the interviewer casting doubt on George Carrolls service in Malta, because his name did not appear on any list. I was curious; what were these lists? And how could they not include someone who had served in such a key role for over a year?

Sifting through the many books written about Malta and the Second World War, it seemed that little was known about the role played by army bomb disposal in the defence of the Island. This was surprising, given what I knew of Lieutenant Carrolls experiences, and considering the extent of the bombing endured by Malta during the conflict. When war was declared, the British outpost of Malta was on the front line of a battle to control convoy routes through the Mediterranean supplying forces fighting in North Africa. Malta stood alone, with her enemies just 60 miles to the north. The nearest Allied territory was almost 1,000 miles away. As the Axis powers embarked on a determined campaign to eliminate Malta as a vital Allied stronghold, the Island faced the second major siege in its history. In 1565 an Ottoman Turk enemy was defeated by the Islands natural and man-made defences, combined with the resilience of its people. In the twentieth century, Malta would bear the brunt of a new and devastating type of war: blitzkrieg. Even after the shock at German bombing during the Spanish Civil War, there was little realisation at the start of the Second World War of the scale of terror soon to be unleashed on civilian populations.

Malta is just 17 miles (27km) long and 9 miles (14.5km) wide an area similar in size to Greater London. In 1940 most of the population was concentrated within a six-mile radius of its Grand Harbour and close to key enemy bombing targets: the airfields, dockyard and submarine base. During March and April 1942 alone, the tonnage of bombs dropped on the Island was double the total for the whole of the worst year of the Blitz on London. Inevitably among the thousands of tons of bombs which fell, many failed to detonate. Unexploded bombs (UXBs) lay in the narrow streets, lanes and fields, a continuing menace to life and property long after the all-clear had sounded. Finding an unexploded bomb, the Islands people turned to the Royal Engineers (RE) Bomb Disposal officer. Every bomb which fell on Malta and Gozo and did not explode was his responsibility, unless it lay on an airfield or within the Royal Navy dockyard.

The RE Bomb Disposal officers job was to respond to a report of a UXB and decide how it would be dealt with, at minimum risk to military operations, the civilian population, his own life and the lives of his men. Confronting danger at every incident, he had to be courageous, self-disciplined, technically adept and methodical. It was said that no-one volunteered for the job; thrill-seekers, and anyone who would take an unnecessary risk, would be a liability. At the site of a UXB, he had absolute authority over everyone, from ordinary civilians to the highest ranking officer and had to be prepared to use it. The NCOs and sappers of RE Bomb Disposal also worked under constant threat of explosion. Strict conformity to army regulations was not always the best response to their situation. They needed to use their initiative and act on it.

Next page