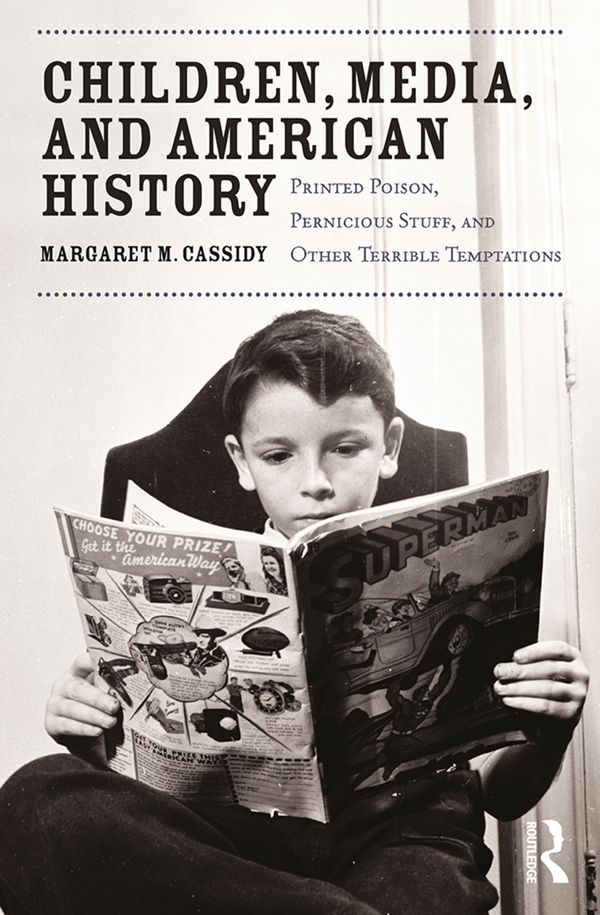

Children, Media, and American History

Printed poison. Pernicious stuff. Since the nineteenth century, these are some of the many concerned comments critics have made about media for children. From dime novels to comic books to digital media, Cassidy illustrates the ways children have used old media when they were first introduced as new media. Further, she interrogates the extent to which different conceptions of childhood have influenced adults reactions to childrens use of media. Exploring the history of American children and media, this text presents a portrait of the way in which children and adults adapt to a constantly changing media environment.

Margaret M. Cassidy is Associate Professor in the Communications Department at Adelphi University, USA. She is the author of BookEnds: The Changing Media Environment of American Classrooms.

First published 2018

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

and by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2018 Taylor & Francis

The right of Margaret M. Cassidy to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical,

or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cassidy, Margaret, author.

Title: Children, media, and American history : printed poison,

pernicious stuff, and other terrible temptations / Margaret M. Cassidy.

Description: New York : Routledge, 2018. | Includes bibliographical

references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017020214 | ISBN 9781138849914 (hardback) |

ISBN 9781138849921 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781315725116 (ebk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Mass media and childrenUnited StatesHistory. |

Television and childrenUnited StatesHistory. | Childrens

literaturePublishingUnited StatesHistory. | ChildrenBooks

and readingUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC HQ784.T4 C295 2018 | DDC 302.23083dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017020214

ISBN: 978-1-138-84991-4 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-84992-1 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-72511-6 (ebk)

Typeset in Bembo

by Apex CoVantage, LLC

For Justin and Molly

In 1858, a minister named Alfred Beach delivered a sermon titled Our Children: Their Dangers, and Our Duties. He talked about the difficulties of raising children at a time and in a place filled with obstacles and perils.

These people were neither the first nor the last adults to worry about the fate of children in changing times with changing media. From Socrates concerns about writing to contemporary adults worries about smartphones and social media, a common theme in media history is that new media change childrens access to information and ways of interacting with others, and while kids are typically having a pretty good time with those media, adults are worrying that this might not be such a good thing.

For most people, the term new media most likely conjures images of smart phones, tablets, camera-equipped drones, and other devices that have recently become available to us. But all media were once new media, and looking carefully at how they were received, used, and resisted helps place todays reactions to new media in context. Writing about todays new media, Lisa Gitelman and Geoffrey Pingree argue that the same sorts of issues and anxieties surrounded the emergence of other media. Indeed, it seems that technological Many of the individual stories of the new media that were attractive to children have been thoroughly told; for example, the concerns about film that produced the Payne Fund Studies and the Hollywood Production Code, or the fears about comic books that sparked Fredric Werthams Seduction of the Innocent crusade, are fairly well known. What we need now is to bring these stories together, in one place, as a history of new media that focuses on the way these media entered the lives of children.

Although each of these stories is unique, occurring in a particular time with its own social, political, economic, and cultural concerns and priorities, taken together they constitute what can be called an episodic notion. James A. Gil-bert describes the episodic notion as the reappearance of an old worry. Its roots lie in a reoccurring criticism of American culture attributing misbehavior and delinquency to a hostile cultural environment. In the case of new media and children, the fears that adults express are often less about the actual medium or its content and more about larger questions of what is happening in the culture at that moment and how it affects adults interactions with, and influence on, children. Examining these stories of individual media together, as individual parts of a larger story, helps reveal those underlying concerns by exposing the common reactions of people to those media. It invites us to wonder about why people, in so many different times, places, and contexts, reacted in essentially the same way, regardless of all the differences that might have contributed to more variation in their responses.

In particular, the episodic aspects of these stories contain elements of moral panic, a term that is both useful and problematic. The term implies a reaction out of proportion to the situation, which may have some truth, but which overlooks the legitimate concerns that people might have about what is happening to them. Sarah J. Smith criticizes the term for emphasizing issues of manipulation and irrational concern, while obscuring the fact that those involved in panics are usually responding in what they consider a rational way to a genuine threat. For example, it might seem ridiculous today that nineteenth century parents thought that cheap fiction might encourage their children to become outlaws or runaway brides. However, the mass press had exploded onto the scene, and children really did have a great deal more access to information that had not been curated by their parents and that really did offer perspectives that were often in conflict with those of their parents. Similarly, although fears about 1950s media and youth culture sound a bit over the top today, it was perfectly reasonable for adults to be concerned. They had just witnessed the way that media were used as one means of justifying the Holocaust in the minds of otherwise normal, ordinary people. Could media be used to do something like that to their own children? It was not so far-fetched to wonder about things like this, so labeling that wondering an irrational moral panic may not be fair.

New media in the United States have generally been met with a mix of fascination and fear. There was plenty of excitement about how the telegraph could bind together a nation that was expanding, diversifying, and struggling to hold itself together in spite of some very deep-seated conflicts; there was also a lot of confusion and superstitious thinking about what it could and could not do. Although a more balanced approach to media change might produce a more satisfying and comfortable integration into peoples lives, the typical American response has been much more polarized, making it difficult to react thoughtfully to the real gains and losses that those changes produce.