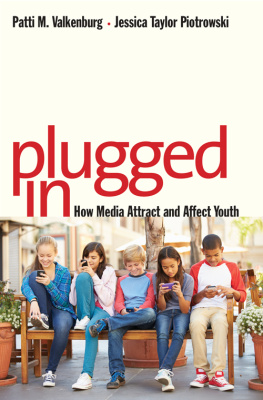

PLUGGED IN

Copyright 2017 by Yale University.

All rights reserved.

Subject to the exception immediately following, this book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

The author has made an online version of this work available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. It can be accessed through the authors Web sites at www.ccam-ascor.nl, www.jessicataylorpiotrowski.com, and www.pattivalkenburg.nl.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Galliard Old Style type by IDS Infotech Ltd., Chandigarh, India.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016953447

ISBN 978-0-300-21887-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

FOR PAUL AND JOHN

CONTENTS

PREFACE

In the past decades, a dazzling number of studies have investigated the effects of old and new media on children and teens. These studies have greatly improved our understanding of why youth are so massively attracted to media. And they have also shown how children and teens can be affected by media, in positive and negative ways. Plugged In provides insight into the most important issues and debates regarding media, children, and teens.

Plugged In discusses the dark sides of media, such as the effects of media violence and pornography. But it also discusses their sunny sides, such as the countless opportunities of educational media for learning, and the potential of social media for identity development. Each chapter gives an overview of existing theories and research on a particular topic. This general literature review is occasionally illustrated by our own research findings. The book covers research among infants (up to 1 year old), toddlers (13 years), preschoolers (45 years), children (512 years), and teens or adolescents (1219 years). Within these general age groups, we sometimes refer to subgroups, such as tweens (812 years), early adolescents (1215 years), and late adolescents (1519 years). We use the term youth to refer to both children and adolescents.

Plugged In is based, in part, on Responses to the Screen (Erlbaum, 2004), by Patti Valkenburg. Additionally, it draws on her Dutch book published in 2014 by Prometheus. But whereas that book focused primarily on Dutch data, this one internationalizes and updates both the research and the examples of media and tools. Incidentally, doing so was less difficult than we anticipated, because the preferences of youth in Western countries are remarkably homogenous. For example, a cartoon or digital game that is popular in the United States is very likely to be popular in most other westernized countries.

We see this book, like Valkenburgs earlier ones, as an informative device for anyone interested in the study of children, adolescents, and the media. We are grateful that Yale University Press gave us the opportunity to publish an open-access book whose online version is free to students and researchers all over the world. We hope you enjoy reading the book as much as we enjoyed writing it.

PLUGGED IN

YOUTH AND MEDIA

My dear, here we must run as fast as we can, just to stay in place. And if you want to get somewhere else you must run at least twice as fast as that.

Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass (1871)

Over the past few decades, there have been several thousand studies about the effects of media on youth. And yet, somewhat paradoxically, we still have much to learn. In part, the gaps in our knowledge are due to dramatic changes in young peoples media use. In the 1990s, children and teens spent on average four hours a day with media; these estimates have now skyrocketed to an average of six (for children) and nine hours a day (for teens). As a matter of fact, todays children and teens spend more time with media than they do at school. And indeed, some of us are less concerned about what youth are learning in school than about what they are picking up from their many hours with all those screens.

Along with the significant growth in media use, the gaps in our knowledge are caused by the sweeping and rapid changes in the media landscape. New media and technologies are developing and replacing one another at a dramatic pace. Social media tools that we studied not long ago now seem as old as Methuselah. In 2015, virtually all teens had Facebook accounts, yet even a juggernaut like Facebook has to continually do its best to stay ahead of the competition and not lose its users to newer, more attractive interfaces such as Snapchat, Taptalk, and so forth. Indeed, the truth of the epigraph from Through the Looking-Glass is compelling: in the new media landscape, we must run as fast as we can, just to stay in place.

The commercial environment surrounding youth is experiencing major changes, too. Traditional TV advertising has lost its dominant position. The discrete thirty-second commercial is no longer the best way to reach young people. Instead, advertisers are being forced to create and implement other, often more covert forms of advertising, such as product placement and advergames. Todays James Bond will gladly order a Heineken, and Mad Mens Don Draper a Canadian Club whiskey, which, according to its makers, has boosted the sales of whiskey among teens. And thanks to cross-media marketing, Dora the Explorer has become more than a TV series; there are Dora apps, Dora games, Dora toys, Dora quilt covers, and Dora websites in dozens of languages.

Then there is the world of games. In the 1990s, gaming was considered the domain of teenage boys, but it has increasingly become mainstream for young and old, male and female. Ten years ago, a mention of video games brought with it images of a home computer or a console player such as Nintendo or PlayStation. Games such as Street Fighter, Super Mario Bros, and Counter-Strike are probably among the first to come to mind. When we think of games today, our first thoughts are likely to be Pokmon GO or Candy Crushgames that can be played with smartphones or tablets. Touch-screen technology and the Internet have profoundly influenced what gaming looks like.

We see now that even very young children are playing games with their parents smartphones, and that the gender divide is changing as girls find their own game spaces in virtual worlds such as Club Penguin and Neopets. Virtual gaming worlds, in general, have spiked in popularity: the game Minecraft is among the highest-grossing apps of all time. This increased access to gaming on touch-screen platforms, combined with a reliance on freemiums (that is, apps that are free to download and rely on advertising and in-app purchasing), has provided formidable competition to traditional console game manufacturers.

Academic Interest in Youth and Media

In parallel with these wide-ranging changes in the media landscape, the topic of youth and media has acquired greater significance in academia, drawing interest from more and more scientific disciplines. Within psychiatry and pediatric medicine, there are countless studies of the effects of media use on aggressive behavior, attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and obesity. Neuroscientists are researching whether media use causes changes in brain areas responsible for aggressive behavior, spatial awareness, and motor skills. Sociology is studying the dynamics of youth cultures and teenage behavior in online social networks.

Next page