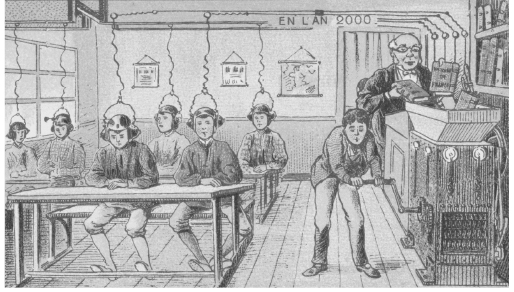

Created in 1899, Jean Marc Cotes vision of a classroom in the year 2000 illustrates the long history of technological fantasies about education. The students are connected to a network by transmitters placed on their heads, although they sit at desks in disciplined rows, all faced towards the front, while the teacher feeds them books via a kind of mechanical mincing machine.

Copyright David Buckingham 2007

The right of David Buckingham to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2007 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-07456-3880-5

ISBN-13: 978-07456-3881-2 (pb)

ISBN-13: 978-07456-5530-7 (Multi-user ebook)

ISBN-13: 978-07456-5531-4 (Single-user ebook)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.polity.co.uk

Preface

It is now more than a quarter of a century since the first microcomputers began arriving in British schools. I can personally recall the appearance of one such large black metal box a Research Machines 380Z in the North London comprehensive school where I was working in the late 1970s; and I can also remember very well the computer program that was demonstrated to the English Department a simple but genuinely thought-provoking package called Developing Tray, a kind of hangman game in which a poem gradually emerged like a photographic image in a developing tray. I also recall, a couple of years later, being involved in a research project called Telesoftware, run from Brighton Polytechnic, where educational software was (amazingly to us at the time) sent over the telephone line and recorded onto little cassette tapes. Actually, very few of the other teachers were interested in the software that was being delivered, but the students in my media studies class were quick to commandeer the equipment to make animated title and credit sequences for their scratch-edited video productions.

Around the same time, the American technology guru Seymour Papert was telling us that computers would fundamentally transform education and ultimately make the school itself redundant. Computers, he wrote in a book published in 1980, will gradually return to the individual the power to determine the patterns of education. Education will become more of a private act (Papert, 1980: 37). Four years later, he told readers even more bluntly, There wont be schools in the future. The computer will blow up the school (Papert, 1984: 38). He was not alone. Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple Computers, then pitching relentlessly to capture the education market in the US, was another passionate advocate of the revolutionary potential of educational computing; and he was later joined by an enthusiastic cohort of visionary marketers, such as Bill Gates of Microsoft, who were keen to use schools as a springboard into the much more valuable home market. Indeed, ten years earlier, the radical theorist Ivan Illich was creating a vision of a deschooled society, in which computers would permit the creation of informal, convivial networks of learners, and schools and teachers would simply wither away (Illich, 1971).

Such predictions about the transformative potential of technology have a very long history, not just in education, and in retrospect it is easy to show that they have largely failed to come true. The wholesale revolution Papert and others were predicting patently has not taken place: for better or worse, the school as an institution is still very much with us, and most of the teaching and learning that happens there has remained completely untouched by the influence of technology. And yet, over the same period, electronic technology has become an increasingly significant dimension of most young peoples lives. Digital media the internet, mobile phones, computer games, interactive television are now an indispensable aspect of childrens and young peoples leisure-time experiences. Young peoples relationship with digital technology is no longer formed primarily in the context of the school as it was during the 1980s, and even into the 1990s but in the domain of popular culture. This raises the fundamental question that I want to address in this book. How should schools be responding to the role of digital media in young peoples lives? Should they simply ignore them as they largely appear to do at the present time? Should they enlist these media for the purpose of delivering the established curriculum? Or can they find ways of engaging with them more critically and creatively?

More than twenty-five years after my first encounters with computers in the classroom, my university research centre was relocated to a new facility, the London Knowledge Lab. Although it is situated in the heart of Londons historic Bloomsbury district, the Knowledge Lab looks to the future: its strapline is exploring the future of learning with digital technologies. In the process, a small team of us who are concerned with children, young people and media have come into closer contact with advocates of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in schools, and with advanced computer scientists. In some respects, it is this encounter and the much broader changes in media, technology and education that it represents that has prompted me to write this book.

My perspective is not that of a technology or computer specialist. Most of my research and teaching has been about media and particularly about moving image media such as television and film. I have explored how these media are produced, the characteristics of media texts, and how children and young people use and interpret them. I have also considered how teachers in schools might teach about these media, and what happens when they do so. Inevitably, in recent years, this focus has expanded to encompass new media such as computer games and the internet. However, I continue to regard these things as media rather than as technologies . I see them as ways of representing the world, and of communicating and I seek to understand these phenomena as social and cultural processes, rather than primarily as technical ones. Technologies or machines are obviously part of the story. But technologies should not be seen as simply a set of neutral devices. On the contrary, they are shaped in particular ways by the social interests and motivations of the people who produce and use them.

Likewise, I would challenge the notion of information technology as though these devices were simply a means of storing and delivering an inert body of facts or data (Burbules and Callister, 2000). The term information somehow implies that the content of communication is neutral and that, like technology, it is independent of human interests. There is also an implication here particularly in the discourse of policy-makers that delivering information will somehow automatically lead to knowledge and learning. In practice, this approach inevitably sanctions an instrumental use of technology in education a view of technology as a kind of teaching aid. Adding communication and widening the term to ICT is a step in the right direction. But, ultimately, we need to acknowledge that computers and other digital media are technologies of representation : they are social and cultural technologies that cannot be considered merely as neutral tools for learning.