COLD WAR, COOL MEDIUM

TELEVISION, McCARTHYISM, AND AMERICAN CULTURE

Film and Culture

A series of Columbia University Press

Edited by John Belton

What Made Pistachio Nuts? Early Sound Comedy and the Vaudeville Aesthetic

HENRY JENKINS

Showstoppers: Busby Berkeley and the Tradition of Spectacle

MARTIN RUBIN

Projections of War: Hollywood, American Culture, and World War II

THOMAS DOHERTY

Laughing Screaming: Modern Hollywood Horror and Comedy

WILLIAM PAUL

Laughing Hysterically: American Screen Comedy of the 1950s

Ed Sikov

Primitive Passions: Visuality, Sexuality, Ethnography, and Contemporary Chinese Cinema

REY CHOW

The Cinema of Max Ophuls: Magisterial Vision and the Figure of Woman

SUSAN M. WHITE

Black Women as Cultural Readers

Jacqueline Bobo

Picturing Japaneseness: Monumental Style, National Identity, Japanese Film

DARRELL WILLIAM DAVIS

Attack of the Leading Ladies: Gender, Sexuality, and Spectatorship in Classic Horror Cinema

RHONA J. BERENSTEIN

This Mad Masquerade: Stardom and Masculinity in the Jazz Age

GAYLYN STUDLAR

Sexual Politics and Narrative Film: Hollywood and Beyond

ROBIN WOOD

The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music

JEFF SMITH

Orson Welles, Shakespeare, and Popular Culture

MICHAEL ANDEREGG

Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema, 19301934

THOMAS DOHERTY

Sound Technology and the American Cinema: Perception, Representation, Modernity

JAMES LASTRA

Melodrama and Modernity: Early Sensational Cinema and Its Contexts

BEN SINGER

Wondrous Difference: Cinema, Anthropology, and Turn-of-the-Century Visual Culture

ALISON GRIFFITHS

Hearst Over Hollywood: Power, Passion, and Propaganda in the Movies

LOUIS PIZZITOLA

Masculine Interests: Homoerotics in Hollywood Film

ROBERT LANG

Special Effects: Still in Search of Wonder

MICHELE PIERSON

Designing Women: Cinema, Art Deco, and the Female Form

LUCY FISCHER

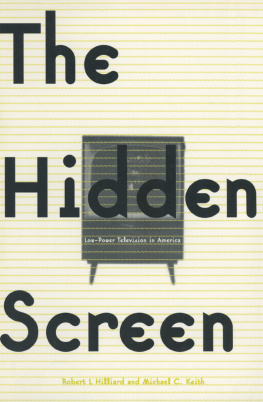

THOMAS DOHERTY

COLD WAR, COOL MEDIUM

TELEVISION, McCARTHYISM, AND AMERICAN CULTURE

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2003 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-50327-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication

Data Doherty, Thomas Patrick.

Cold War, cool medium : television, McCarthyism, and American culture / Thomas Doherty.

p. cm.(Film and culture)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-231-12952-1 (acid-free paper)

1. Television and politicsUnited StatesHistory. 2. Television broadcasting of newsUnited StatesHistory. 3. McCarthy, Joseph, 19081957. 4. Anti-communist movementsUnited StatesHistory. 5. United StatesPolitics and government19451953. 6. United StatesPolitics and government19531961. 7. United StatesSocial life and customs19451970. 8. Cold WarSocial aspectsUnited States. I. Title. II. Series.

PN1992.6.D64 2003

791.45658dc21

2003051501

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy, who died in 1957, lives as a metaphor. No time-bound demagogue, he has long since metamorphosed into a Cold War totem and universal bogeyman, nearly as vivid in the present as he was in the past. Televisiona site for his ascent, the stage for his downfallcontinues to keep his image vital and alive.

Viewed through a gauze of memory and motives, newsreel clips and video snippets, McCarthy and the era named after him are hot combat zones in a fierce Kulturkampf over Cold War America. The man and his -ism have launched a multitude of memoirs, biographies, critical studies, and documentaries, many as ideologically driven as their subject. The historian who presumes to lob another volume onto the pile needs a clear rationale; the reader deserves a frank confession of allegiances.

The outlook for this study of the phenomenon known as McCarthyism is televisual. Rather than a retrospective glance backward via interpretative scholarship, I have viewed the period dating roughly from the late 1940s to the mid-1950s through the lens of television programming and the contemporary commentary about the embryonic medium. Save for a few necessary flash forwards, the window into this chamber of the American past has been the television screen.

Unfortunately, the extant materials are easier read about than looked at. All historians are bedeviled by problems of access and imagination, but researchers into the early days of television have special reason to whine. Until the advent of magnetic videotape in 1956, television came live or on film. Networks treated the heritage haphazardly, and the official repositories of the federal government were oblivious to its future significance. Counterintuitive as it seems, the 35mm film used by the newsreels to chronicle the pretelevision history of the 1920s, the 1930s, and the 1940s is sharper, clearer, and more readily retrievable than the live telecasts of the 1950s. Caught in the interregnum between film and videotape, the passage exists in a kind of moving-image lacuna.

Whenever possible I have watched the original telecasts, but much enticing material is just plain gone, never recorded, vanished into the ether. In these instances, I have relied on transcripts of the shows, trade press accounts, and newspaper reports. Among the pioneering commentators on the medium, I found Jack Gould of the New York Times, John Crosby of the New York Herald Tribune, Marya Mannes of the Reporter, and Dan Jenkins of the Hollywood Reporter especially reliable and astute (meaning that I tended to agree with them).

The archival gaps in the television record are magnified by a problem of perception. Since its official coming out party at the New York Worlds Fair in 1939, television has undergone a series of tectonic changes, audiovisual revolutions akin to the leap from silent film to sound cinema or from theatrical motion pictures to home television. The difference in the programming and technology of television in the 1950s and television in the 1960s and 1970s (during the era of Three Network Hegemony) and in the 1980s and 1990s (during the Age of Cable) is a gulf that the single word television cannot adequately straddle.

However, that one word is used to describe the full life span of the medium, a linguistic holdover that is not only imprecise but deceptive. Yet to invent a neologismpaleo-video, classical television, IKE-TVseems unduly cute. Television will do, with the caution that television then was a different medium than television later, or now, and broadcast over a different cultural atmosphere.

Within that atmosphere, the question of political allegiance weighed heavilythe answer, or the refusal to answer, shaping or stunting a life. Today, the stakes are not nearly so high, but few cultural historians who venture onto the field emerge unscathed from the polemical firefights that swirl around McCarthyism. Thus, though the pages that follow are in the end more about the medium than the man and the isma portrait of television and American culture at a pivotal moment in the history of eachto answer that question once asked under duress and subpoena seems a necessary gesture of self-identification rather than self-incrimination. So, like the Cold War liberal, that now nearly extinct creature, I believe it is not mutually exclusive to conclude that Soviet communism posed a menace to human freedom and that Joseph R. McCarthy was a scoundrel.

Next page