Table of Contents

In the course of our decades-long struggle against

an oppressive political regime in Bengal, many

Trinamool Congress workers lost their lives.

This book is dedicated to them;

my parliamentary career is a tribute to their sacrifices.

CONTENTS

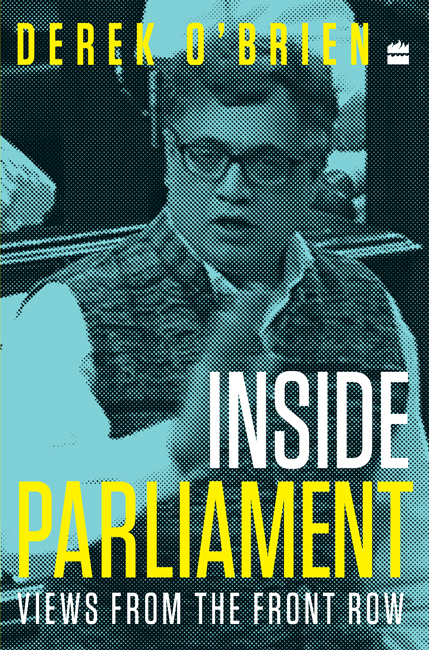

After six years as a member of Parliament and close to fifteen years in politics, I felt it was time to put down my thoughts and ideas, my political interventions and policy suggestions, in a book. Im not an expert on every subject under the Delhi sunother than news television anchors, nobody is. Yet, as the leader of my party in the Rajya Sabha, and chief national spokesperson of the All India Trinamool Congress, I have endeavoured to keep abreast of current policy debates and concerns. I have tried to either study them or meet people with keen and often differing insights.

Sometimes, ones policy position is instinctive and logical. It flows from ones ownor the partysphilosophy and innate sense of right and wrong, fair and unfair. On other occasions, the policy position arrived at is the product of intense investigation and inquiry. A serious parliamentarian or politician intending to make a mark in a policy debatewithin his or her party, in Parliament or in wider public lifeneeds to do as much homework as a diligent student.

That is why I have often referred to the calling of politicsand it is a calling, not a profession or a jobas a lifelong university. You never graduate; you are constantly learning, if you choose to.

Parliament has been both a university and a sacred shrinea shrine to the ideals of our Constitution. It is these ideals of the Constitution that have allowed me, the member of a small minority community, to enter Parliament and contribute there. Not too many countries and political systems allow their citizens such a right.

To me, this Constitution speaks for our shared existenceone that allowed a Christian boy to grow up in a predominantly Hindu neighbourhood in Calcutta, on a road named after a Muslim, with Parsis, Sikhs and Jews as close friends. I am not unique. Millions in India share my privilege. The Constitution ensures that for us, and Parliament is an embodiment of the Constitution and its foundational principles.

This book is a collection of essays on various themes that have exercised me in my political career and in my attempts to contribute to the shaping of public debate and policymaking. It is also a catalogue of my first term in Parliament. All the themes of the essays have, in some form or another, been the focus of hectic contestation and argument in recent times. In that sense, this is a book on contemporary subjects of political and policy interest. No doubt there are other topics too that fit that definition, but the ones here happen to be those that I have embraced more strongly than others.

There are forty-six essays in this collection. They fall under five broad categories and I would like to explain how I came to choose them. That process of selection is important for meand, I hope, for my readerbecause it says a lot about who I am as an individual, as a public figure and as a politician. In a sense, these five categories open a window to me as much as, I believe, a window to todays India.

The first , Parliamentary Affairs, comprises my observations, lessons and learnings from my six years in Parliament.

I slipped in as a backbencher and, gradually and pertinaciously, made it to the first row. I remember my first day and my first questiona supplementary question asked on the spur of the moment to then Human Resource Development (HRD) Minister Kapil Sibal, on whether the government had statistical data on how much foreign exchange Indian students were remitting for higher education overseas. It was a question very close to my heartmy father and grandfather were both educationists, and my professional association with schools and colleges has been a long one.

Yet it was not as if I had planned to ask it. It was while listening to the ministers answer to another question that this point struck me and I put up my hand without thinking. The chair probably noticed a new face and decided to give me a chance. And so it began.

I have imbibed a lot in Parliament. The tactics of day-to-day management and the strategy of achieving a long-term legislative objective; preparing for a debate or even an effective intervention; watching a riveting exchange between Arun Jaitley and P. Chidambaram, two seasoned debaters and, to my mind, among the most accomplished parliamentarians in any democracy; the role of the Upper House in our constitutional frameworkall these find mention in this section.

The second is The State of the Nation. It covers a range of political events, episodes and currents, each of which speaks of a pressing and ongoing problem. From the situation in the Kashmir Valley and the challenge of the Internet in the context of the turbulence there to the hollowness of Union government policy on womens issues; from the politics of religious and caste supremacismon both of which I have extremely strong viewsto how Indias spirit of pluralism is slowly being eroded. I expect this is the section that will get me the most likes as well the most dislikes.

Section three is Saying It Like It Is. The eleven essays here are straight from the heart. They flow from my personal and, in some cases, pre-political experience, including with the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI[M]) in Bengal. I explain my aversion to bans, especially on food and speech. I speak of the so-called national media, which, Ive long feltand this is a belief confirmed after six years in the Rajya Sabhais incapable of understanding reality beyond central and south Delhi. And maybe the tony parts of Gurgaon and Noida.

The fourth section is The Economics of It. For the most part, this is a critique of the economic policies followed by the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government. There is a series of essays on demonetization and its aftermath. It gives me no happiness to say that we in the Trinamool had anticipated that it would be a fiasco, and I delineate why the negative impact of a hare-brained scheme will haunt the country for years to come. Demonetization was a scandal. That is the only way to describe it.

Im more optimistic on the Goods and Services Tax (GST), despite serious quibbles about its hasty roll-out by the NDA government. On the obsession with foreign investment, I am equally critical of the NDA government and, on occasion, of its predecessor, the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government. They often have the same lazy approach and even borrow each others language and excuses. However, some of the economic policies they have imported to and imposed on India simply do not suit our society and our people. Failure is written into them.

The final section is The Greater Common Good. Even if I were to put it myself, the ten essays in this section attempt to go beyond political differences and identify solutions to specific problemsurban governance, where a Calcutta and a Mumbai, for example, can borrow from each others best practices; or seeking to build a consensus on priorities for the Indian Railways, an institution I have been involved with in my capacity as a legislator and political administrator, and one that several generations of my mothers family served with affection and distinction.

In this section, there is a chapter that I wrote with more emotion and feeling than usualA True Leader Forgets No One. This is my recollection of more than a dozen years of working with Mamata Banerjee, founder and leader of the Trinamool Congress and chief minister of Bengal, and the person who has taught me almost everything I know in politics. She has mastered, and has tried to teach my colleagues and me, the big picture of politics. But her key strength, as I point out, is in never forgetting the details and the people that make up the Trinamool ecosystem and our political family.