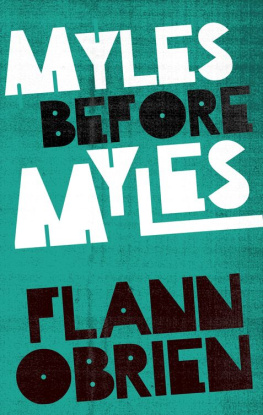

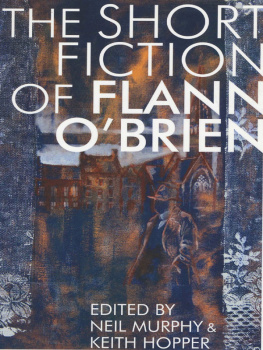

Nothing is easy to pin down about the author of this book, particularly his various personae, or the names he adopted for them when appearing in print. For my purpose it is simplest to call him Myles, as Myles na Gopaleen was the name he is best remembered by for his excursions into the columns of newspapers. However , this is not simply a supplementary volume to TheBestofMyles, which was a selection from Cruiskeen Lawn, the column he wrote for the IrishTimes over a period of twenty-five years, because in writing an entirely new column, Bones of Contention, for the NationalistandLeinsterTimes he adopted not only a new name, that of George Knowall, he also took on a new persona, that of a quizzical and enquiring humorist who might be found in a respectable public house in Carlow. It had been my intention originally to make a selection from both the Nationalist and the SouthernStar, Skibbereen, but the John James Doe of A Weekly Look Around never managed to become a person in his own right, and the column was patchy and tailed off after the first year and barely saw out a second, albeit there were one or two typical Mylesian pieces. To have included them here would have been a disservice to the man who addressed himself faithfully to his Carlovian readers.

One of Myless remarkable achievements as a columnist was that of consistency supported by a spring of imaginative energy; for whatsoever the vicissitudes of life generally, and those attaching to people in and around newspapers in particular, he maintained an extraordinary output right up to and including the year of his death in 1966. Another remarkable strength was the quality of his writing. Homer nods, but Myless delight in language never leaves him and whether he is writing on the seasonal and annual events, the weather or the Dublin Horse Show, he is always able to make something fresh. To write well is not easy, nor is it a gift like perfect pitch; it is difficult and demanding. No one could pick his way round the hazards of journalistic clichs with such deftness as Myles, nor turn them to such good use when it suited his need, as in the Myles na Gopaleen Catechism of Clich, with which he rewarded the devoted followers of Cruiskeen Lawn.

The persona he presented to the people of Carlow, under the name of George Knowall, was different from the one who addressed the plain people of Ireland in the IrishTimes, yet his felicitous use of language, his delight in words, and his uncanny ability to see through humbug and cant were employed to the same end.

To those admirers of Myles who know a little about his life, he drops various autobiographical hints that can be picked up and enjoyed. Since what happens to him is as much grist to his mill as are the absurdities recorded in the daily papers, we nearly always get a bulletin about his health when upset, and a gentle swipe at the medical profession and the undignified absurdity of being in hospital when the misfortune arises, as it does periodically in the following pages. We are treated variously to a broken leg, influenza (with a note about a lady who survived an operation when young and spent the rest of her life talking about and embellishing the event), vaccination, a phantom heart-attack wrongly diagnosed, convalescence, hospital treatment, and the operation that probably concerned his last illness. Doubtless he would have agreed that there is only one fatal illness, the one that kills you, and would have used this unfashionable medical apophthegm as a text. Certainly his absence from the pages of the Nationalist was of long duration preceding the appearance of the operation piece, but nowhere is the sharpness blunted or his verbal enthusiasm dampened in any of the pieces he wrote after his return.

The Myles of the Nationalist is eminently sensible and proclaims himself born into a lower middle class family, something that connotes, of course, ultra respectability, carefulness amounting to perhaps contempt of the real poor . And it is from this position that he writes in these pages, though he personally was never victim to the hypocrisies inherent in that position. He delights in curious and arcane knowledge, though he has no time for facts as purveyed say in radio quiz programmes or in the GuinnessBookofRecords, a book full of extraordinary allegations, for the veracity of which no source or proof is given. When he himself takes an interest in something, such as the word dowse, and follows it through all its meanings and implications, we get a truly adventurous and delightful journey with a courteous and attentive guide.

The Myles of the Nationalist is erudite, urbane and informative and on the whole a country cousin to his metropolitan self. I have seen no reason to arrange the material here under subject headings, since he treated his readers with such attentiveness that the pieces are better read chronologically, as they were published, one subject written about once being taken up again at a later date. The provincial Myles was always mindful that his readership was a loyal and local one and he goes out of his way to address Carlovians as such, taking the trouble as often as not to allude to recently published matter in a previous edition, whether an article or an editorial comment. One such, a feature on agriculture, encourages and this against the tide that took Ireland into the Common Market a gentle attack on agriculture as being alien and un-Irish, claiming that in a study of Irish poetry from 1500 to 1750 there is no mention of the subject, save allusions to pasturage, hunting and the keeping of domestic livestock, including deer. Normally, the supplementary matter in a newspaper which devotes a special feature to a subject supports the burden, its central aim being to attract advertising, and it would appear that Myles was as much a licensed jester in the Nationalist as he was in the IrishTimes. Indeed, the delight we take in a humorous columnist, from Beachcomber to Peter Simple, is that he can take the mind away from the ponderous absurdities of the editorial and the obsessional attention to the topicalities of the day, and enable us to see things in a truer perspective, for comedy is as much at the heart of the matter as is tragedy, and likewise as durable. Not many columnists can justify publication in book form.

As the George Knowall of the Nationalist is a country relation of the Myles of Dublin, so they are both part of a composite human being who wrote those extraordinary works TheThirdPoliceman, AtSwim-Two-Birds and the play FaustusKelly. For the two former he chose the name of Flann OBrien and it is difficult sometimes to reconcile even two different Flann OBriens as one and the same author. There are tides in the affairs of men, surmount them as we may, that do have a profound influence on the direction a mans life takes.

James Joyce didnt let World War I interfere with his single-minded literary endeavour, while it involved the whole of Europe in carnage and massacre and dominated the lives or fortunes of many other writers, both Irish and English; but World War II forestalled the appearance of TheThirdPoliceman by over twenty-five years and made it a posthumous publication. There are various ironies in the life of the author that are almost as mysterious and other-worldly as the events in AtSwim-Two-Birds and TheThirdPoliceman and who knows what might have happened had the latter book been published rightfully as it was written, immediately after AtSwim-Two-Birds. I myself have unearthed two characters in