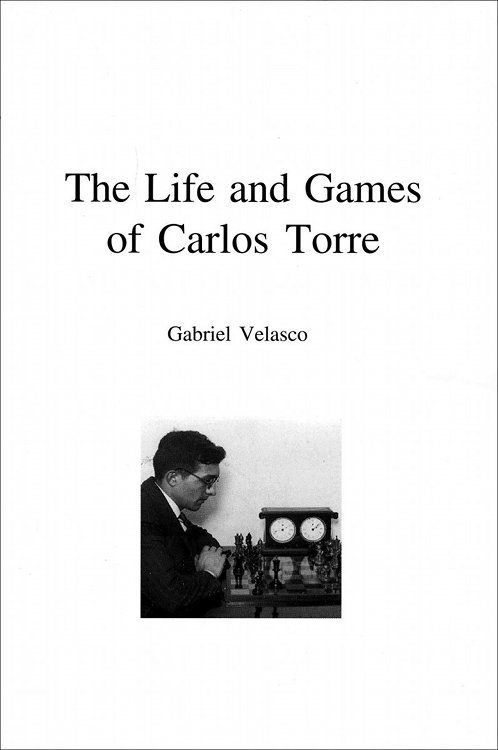

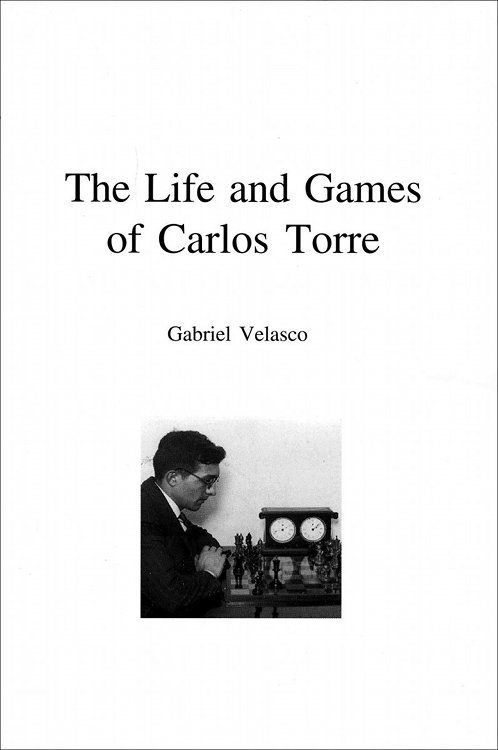

The Life and Games of Carlos Torre

Gabriel Velasco

Russell Enterprises, Inc.

Milford, CT USA

The Life and Games of Carlos Torre

Copyright 2000, 2011

Gabriel Velasco

All Rights Reserved

ISBN: 978-1-936490-38-7

This is a revised, expanded edition of Vida y Partidas de Carlos Torre which originally appeared in Spanish in 1993. Translated from Spanish by Taylor Kingston.

Published by:

Russell Enterprises, Inc.

PO Box 3131

Milford, CT 06460 USA

http://www.Russell-Enterprises.com

Printed in the United States of America

From the Author

In 1993, Vida y Partidas de Carlos Torre appeared, published by Incaro. The current work began as a straightforward translation of that work, but the author, working closely with the translator Taylor Kingston, expanded the orignal manuscript and the result is this English edition.

This book is offered to chessplayers and enthusiasts of all Spanish-speaking countries as an homage to one of the greatest Latin American chess players of all time: grandmaster Carlos Torre Repetto, originally from Yucatn, Mexico. In recognition of Torres formidable accomplishments and triumphs during the years 1924-1926, the Fdration Internationale Des Echecs (FIDE, the International Chess Federation) in 1977 bestowed on Torre the title of International Grandmaster.

The author visited Torre in the town of his birth, Mrida, where he passed away a year later. Though Torre knew the intent of this book, it is sad that he did not live to see it realized.

Those who knew Carlos Torre recall him as an unaffected person of noble sentiments. His health was always fragile and he suffered constantly from insomnia. In his book The Psychology of the Chess Player, Reuben Fine described some of Torres eccentricities, as well as the nervous breakdown he suffered in October 1926, which forced him to retire permanently from chess at the age of 21. Fine related that Torre could never sleep more than two hours a day and described some of his strange habits, such as eating 12 pineapple ice cream sundaes in a day and other such extravagances. In this book we will make no attempt to psychoanalyze Torre, nor will we indulge in theorizing about his untimely and unexpected retirement from chess, in which respect he was similar to some other grandmasters. Our major concern will be to present Torres great games, his beautiful combinations and his strategic and tactical concepts.

The author was able to compile about 170 games of the Yucatan grandmaster, which were narrowed to a selection of 100 of the best, though, in fact, the final total turned out to be 105. We have included four losses and a number of draws, but the great majority of games offered were, logically, won by Torre. Naturally, many trips, letters, and inquiries were necessary to assemble the games.

The author would like to express his gratitude to all those who assisted in the collection of the games, the biographical data, and the tournament tables, including Dale Brandreth, the late Alice N. Loranth, Julieta viuda de Gilberto Repetto Miln, Alejandro Bez and Taylor Kingston. To all these people, my sincere thanks.

Gabriel Velasco

Len, Guanajuato, Mexico

March 2000

Biographical Portrait of Carlos Torre

Little is known of Carlos Torres childhood and early adolescence, the years which gave rise to his love for chess. He was born the 23rd of November, 1904, in Mrida, Yucatn province, Mexico. Carlos was the sixth of seven siblings (four boys and three girls). It is known that his father, Ejidio Torre, taught him to play chess at an early age. According to Carlos, he learned the moves of the pieces at age six, by observing the games between his father and his older brother, Ral. In 1915, when Carlos was not yet 11, the Torre family moved to the United States, settling in the city of New Orleans, Louisiana, birthplace of the legendary Paul Morphy. The reason for choosing this particular city was perhaps merely geographical, as the distance between Mrida and New Orleans is relatively short, even less than that separating Mrida from Mexico City. Of course, in those days it was relatively easy for a Mexican to enter the United States and settle there for short, long or indefinite periods. The problem of undocumented or illegal aliens did not then exist.

Within a few months of his arrival in New Orleans, Carlos quickly learned to read and write English, and he began to frequent that citys chess circles. His first chess books were those of James Mason (The Art of Chess and The Principles of Chess). In one of those appears a great number of combinational exercises and brilliant games with colorful tactical themes, which undoubtedly influenced the style Torre would eventually acquire. At age 13 his chess talent became apparent to Edward Z. Adams, a chess organizer well-known in the United States. At that time, Adams served as vice-president of the New Orleans Chess, Checkers and Whist Club and he gladly took on the role of guide and mentor to the talented youth.

It was natural that under such conditions young Torre made very swift progress. At age 14 he was already considered the second best chessplayer in New Orleans, after the veteran Leon Labatt. That year, the magazine The Good Companion dedicated an entire page to the Mexican prodigy, along with a photograph showing the boy Carlos and Edward Adams at the board, surrounded by the leading players and personalities of the New Orleans chess world. The title ran A new Paul Morphy has been discovered in the Old French City (as New Orleans is sometimes called). The article further said Master Carlos Repetto, 14 years of age, solved eight of the most difficult chess problems from the Washington Birthday Problems in less than an hour, and added In a simultaneous exhibition against 10 of the best chessplayers in New Orleans, he won eight games and drew two. Our vice-president, E. Z. Adams, discovered the young star, who comes from Yucatn, Mexico. (Translators note: At the time this book was translated, the original English versions of the preceding Good Companion text, and of some other texts quoted elsewhere in the book, were no longer available. What you read here are re-translations into English from the authors Spanish versions. These should be close to the originals, but not necessarily identical.)

In 1922, Carlos Torre won the championship of New Orleans, and a year later won by a wide margin the Louisiana state championship, a double round-robin 8-man tournament. For unknown reasons, this tournaments games were not published by any New Orleans newspaper. The New Orleans Times-Picayune had had an excellent chess column, but this ceased in 1919. Only one game from the event is known to have survived (game 1 of this collection, Labatt-Torre), thanks to Torre himself, who included it in his booklet The Development of Chess Ability. The oldest known game of Torres dates from 1920, when he was 15 years old, that being the famous loss to his mentor E. Z. Adams in a game featuring an amazing combination with repeated Queen sacrifice offers and threats of back-rank mate. However, there is considerable doubt that such a game was actually played. The score is given as game 103 of this collection, together with a discussion of its historical validity.

Here it is pertinent to note a peculiar trait of Torres character, and of his attitude toward chess, one which partly explains the enigma of his unexpected and premature retirement from competition. This trait was identified by the master Alejandro Bez, who lived with Torre for years and was able to observe many details of his personality. Ironic though it might seem, Torre never cared for the idea of struggle and competition inherent in chess. For Torre there never was the thrill of victory, the agony of defeat, because for him chess was foremost, perhaps solely, an art form. Torres pleasure in a game came from its artistic, aesthetic value, independent of whether he had won or lost. In his later years, well after retiring from international competition, he was in the habit of playing offhand games with friends, obtaining a won position, and then surprising his opponent with a draw offer. When Torre won a beautiful game he would still sometimes feel regret, even actual suffering, at having inflicted a defeat on his opponent. Many of the great chess champions, such as Alekhine, Fischer, Tal, Karpov, Kasparov et al have been characterized at the board by a confrontational indomitability, the aggressive attitude of a gladiator. Carlos Torre had a comparable degree of chess talent, but was lacking this competitive malice, often bordering on cruelty, seen in some of the greatest chessplayers. It was not an exaggeration when Boris Spassky said of Anatoly Karpov that he radiated an aura of enmity comparable to a crocodile. No such thing was ever said of Carlos Torre. In contrast to Alekhine, who was known occasionally to falsify game scores and notes to make himself appear stronger, in the 1920 Adams game incident Torre may have changed a game score for the sake of beauty, even if it meant portraying himself as the loser.

Next page