Contents

Guide

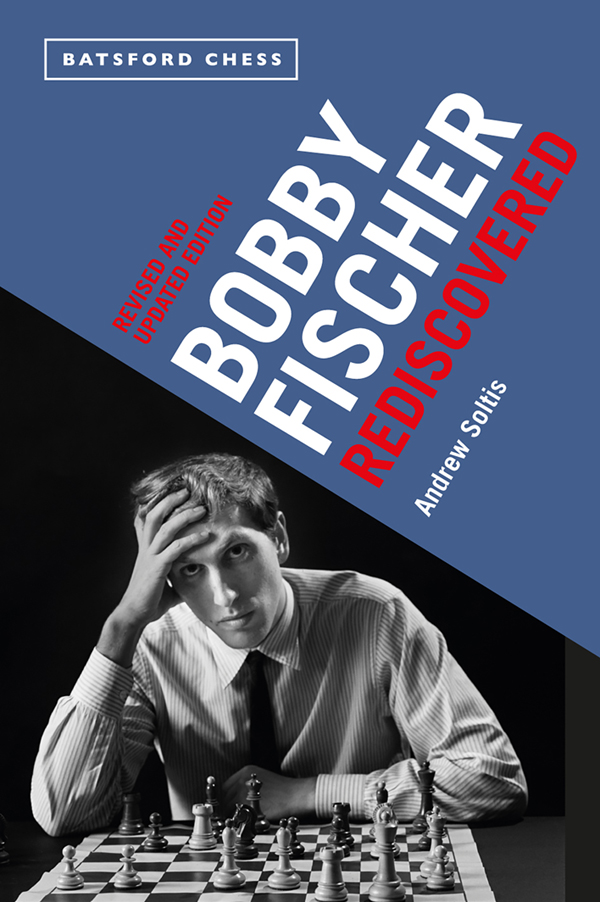

Bobby Fischer Rediscovered

New updated, expanded and re-analyzed edition

Andrew Soltis

Contents

Authors Note

Nearly a decade after Bobby Fischer won the worId chess championship and then disappeared he was living secretly in San Francisco. For months in 1981 he was the house guest of Grandmaster Peter Biyiasas and his wife Ruth Haring a few blocks north of Golden Gate Park. Fischer felt he was living underground, freed from the public attention he said he hated. Fischer had developed a deep interest in all things Indian. He convinced Biyiasas to go with him to see a motion picture made in India. It was playing at a movie theatre some distance away so they decided to take a city bus. Fischer insisted they sit at the back of the bus so he wouldnt be recognized. All went well until a young man got on at the front of bus and, after finding a seat, looked back and stared. Biyiasas realized he was a regular member of the busy Bay Area chess community.

Fischer became upset. I hate it when they recognize me, he told Biyiasas.

What do you mean recognize you? Biyiasas replied. Chessplayers havent seen you in years. You dont even look the same. He recognized me said Biyiasas, who had won several major California tournaments.

For the rest of the bus ride, until the starer got off, Fischer and Biyiasas argued about who was the real target of the starers attention.

This was one of the many contradictions in the life of Fischer. He craved fame and fiercely disdained it. He lived most of his life like a miser but demanded huge (for his time) amounts of money. He said all he ever wanted to do was play chess then virtually gave up the game at age 29. He was deeply religious but kept changing religions. He was a fanatic about his health yet refused the common medical treatment that would have prolonged his life for many years.

Why was Bobby the way he was? I suspect that many of his quirks came from his upbringing. I got a clue to this during my early days as a newspaper reporter.

In October 1972 I was sitting at my typewriter at the New York Post when my desk phone rang. The caller identified herself as Regina Pustan. I recognized the name. She didnt have to add but she did I am Bobby Fischers mother.

She said she had been living in Great Britain for years but had come to America to be interviewed by newspapers. I couldnt believe my good luck. This was just a month after the Fischer Spassky match ended and he was a media phenomenon. He didnt have to be identified by surname in headlines. When he won the final match game in Iceland, my papers front page read simply Bobbys The Champ.

We quickly agreed on logistics: Yes, I could interview her at her hotel. No, I would not need more than an hour. Yes, I could bring a Post photographer. We were winding this up when she casually added that she could not say anything about her son.

I knew that she and Fischer had had a strained relationship. But I was still dumbfounded. What would we be talking about, if not Bobby, I asked?

Why, the election, of course, she said. She had come to the United States to explain to American voters how they must vote. Something simply had to be done to prevent President Richard Nixon from being re-elected the following month.

I understand how you feel, I replied. There are many people who live in America and feel that way. But they would also like to see their opinions given prominent display in the pages of a newspaper with one million readers. Why should we be giving space to someone who had left the United States several years before?

She was shocked by the question. To her, the answer was obvious: Because I am Bobby Fischers mother, she said.

Like her son she expected the respect and attention of a celebrity. But, like her son, she saw no reason to pay the price of publicity. I politely declined to interview her.

I had been fascinated by Fischer for more than ten years. I first saw Bobby one night in late 1961. This was well before my first clocked game in fact, it was not long after Id learned that chess was played with clocks. The occasion, oddly enough, was my grandmothers first and only visit to New York from Newton, Iowa. My mother decided to shock her by taking a stroll through the bohemian streets of Greenwich Village. Walking ahead of them along Thompson Street I spotted a dilapidated storefront that was labeled Rossolimos Chess Studio and convinced my mother and grandmother to drop in for a minute or two. While the three of us stood a few steps inside the doorway to admire the exotic sets for sale, Fischer walked in. Or, rather, lurched in. He never seemed to move in a routine manner, but as a burst of energy.

He was 18, four years older than me, and his oversized suit made him look taller and more rumpled than his 6-foot-2 and 180 or so pounds. He had come to see Nick Rossolimo, the proprietor of the studio, who, I had heard, was some kind of master. I had never actually seen a master but was well aware of Fischer. He explained to Rossolimo that he had just returned from a tournament at a place called Bled and seemed eager to talk about it. I realized that he wanted no, he needed to talk about it to an audience that understood him. He was relaxed, natural and not at all the prima donna Id read about. He was just Bobby. There were four skittles games going on in the cramped studio, but none of the players, who were paying the outrageous sum of 25 cents an hour to play one another, looked up. It struck me that chess was very strange indeed if one of the best players in the world didnt even get a flicker of recognition when sitting a few feet away and talking about his latest success.

The next time I saw Fischer he was playing chess. Not in the same 1600-rated tournaments I was, of course. He was in the U.S. Championship, which had become an annual event, thanks in large part to interest in Fischer. The tournament was held each Christmastime in a Manhattan hotel ballroom. Before each round Hans Kmoch, the tournament director, or one of his assistants would choose which of us young myrmidons would be allowed to operate demonstration boards on the stage. (My friend Russ Garber had learned how the pieces moved only a few months before he handled Fischers 1963 game with Benko, a.k.a. the 19 f6!! game.)

Everyone, of course, wanted to work Bobbys board. If you were lucky, he might send you on an errand, in between moves, to bring him back a container of milk always milk and some food. I never got the chance. Usually I was assigned to a Sherwin-vs.-Mednis or, if I was lucky, a Byrne-vs.-Benko. But seated at the demo board, you were usually only a few feet from the players, so I got a chance to watch Fischer first hand.

He had quick, large eyes that darted about the board as he concentrated, and distinctive eyebrows that always gave away his surprise when he saw something new in his calculations. And he had extraordinarily long fingers. They cradled his head when he went into a deep think which for him meant only ten minutes. Fischer seemed awkward at everything else, even when signing his name in block letters (he apparently never learned script). But when moving the pieces, he exuded a kind of strange, athletic grace. Moving the pieces may have been his most comfortable form of communication. Years later Angela Julian Day told me of her one meeting with Fischer. She was helping to run the Grandmaster Association office in Brussels in 1990. The great promotional hope of the GMA was their World Cup tournaments, and what was supposed to save the Cup from going the way of all previous chess promotions was getting Fischer to play in it. One night Angie went to what she thought was a social get-together with various GMA dignitaries when she discovered the man seated across from her was Bobby Fischer. But Fischer seemed mute. After several clumsy moments of silence, he pulled out of his pocket a well-worn version of the hand-held game in which you move 15 numbered tiles around a plastic grid that has spaces for 16. Fischer indicated that she should mix up the tiles, and then time him with her wristwatch. She did. Fischer unscrambled the tiles in a fraction of a minute. His long, nimble fingers worked remarkably fast. In fact he regarded himself as the world champion at this. And all I could think was what a waste, Angie Day recalled.