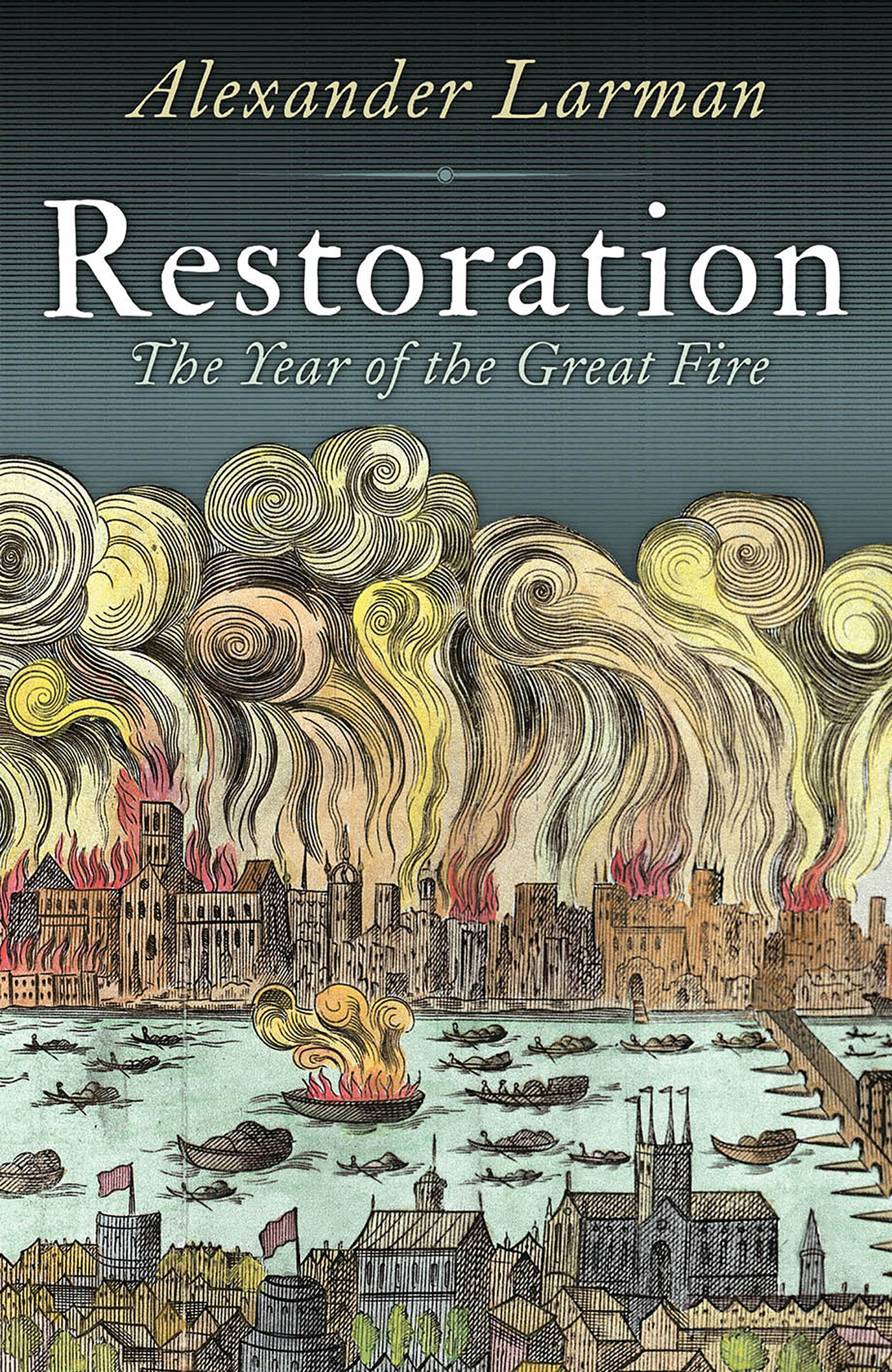

RESTORATION

The Year of the Great Fire

Alexander Larman

www.headofzeus.com

ENGLAND, 1666

The king, Charles II, has beenon the throne for six years. Thecountry is at war with the Dutch.Isaac Newton sits in his mothersgarden and watches an apple fall. Samuel Pepys falls in love with anactress. The subversive preacherJohn Bunyan radicalises the inmatesof Bedford jail. Lord Rochesterbegins a scandalous poetic career.And a fiery reckoning threatensto destroy everything.

In Restoration, Alexander Larman portrays acountry in the throes of social, political and cultural change following the convulsions of Civil War, the rule of Cromwells Protectorate and the Restorationof the monarchy. From bishopsto brothel-keepers, from courtiersto coachmakers, from hawkers tohaberdashers, and from poets toprostitutes, he investigates how thepeople of the time thought, ate, drank, loved and died, bringing alive in vivid detail the England of three hundred and fifty years ago.

For Nancy and Rose

Table of Contents

When the diarist and naval clerk Samuel Pepys wrote his first entry of the year on 1 January 1666, the day had offered little in the way of any particular interest. He was awoken at five in the morning by a colleague, worked solidly without eating or drinking until three in the afternoon, and then, after a dinner mainly spent discussing business with another clerk in the Naval Office, went late to bed. He was not at all vexed by the industry of the day. A summing-up of 1665 in his previous days journal recorded him as having more than trebled his capital, from 1,300 to 4,100, and even the great melancholy of the plague did not affect him; he boasted, I have never lived so merrily, thanks to the company of his friends and the presence in his life of Elizabeth Knepp, an attractive actress with whom he enjoyed a flirtation. He had hopes that the next year would bring more of the same merriment.

At the end of 1666, the tone of his diary struck a different note. Although he was worth a good deal more money 6,200, according to his careful accounting Pepys was irritated to find that he had spent considerably more than the previous year through his negligence and prodigality. He knew that in this he was representative of what he castigated as the sad, vicious, negligent court, which had been responsible for this year of public wonder and mischief [one] generally wished by all people to have an end. Public affairs were in a sad condition, with the countrys enemies great, and grow[ing] more by our poverty. Those sober men like himself had become fearful of the ruin of the whole kingdom this next year. It was a far cry from his optimism of twelve months earlier.

If the Restoration itself can be compared to the supposedly blissful early days of a marriage between king and country in their respective roles of husband and bride, then by the end of 1666 the honeymoon was over. The relationship had become one bedevilled by mistrust and suspicion. The euphoria that had greeted the return of the monarch had been based less on rational expectation of what his reign would bring, and more on a mixture of hope and a misguided belief that he would prove a more able ruler than his father, uniting Parliamentarians and Royalists in an England keen to put the schisms of the civil war behind it. The literate middle classes, represented by Pepys, who wrote about the year with both wit and an insiders view of court, observed those above and below them initially with optimism but also with a growing sense of disquiet. Death stalked the age, whether through ill-advised foreign adventures, poverty and plague or simply brutal capital punishment.

The year itself began with the concluding months of the Great Plague, which killed more than 200,000 people across England, and climaxed with the destruction and chaos of the Great Fire in September, which meant that London had to shake off centuries of history and rebuild itself as a modern and outward-facing world city. Yet this was also a year when many English people believed that the end of the world was nigh, because of the devils number 666 that it contained. A solar eclipse in July struck panic into the hearts of many, who muttered darkly about this new, licentious age, in which those at court adopted foreign customs and the king was married to a Catholic. Englands relations with her European neighbours continued to be troubled. The disastrous Second Anglo-Dutch War was fought in vain pursuit of mercantile advantage; it saw one of the longest naval skirmishes ever fought, the Four Days Battle of early June 1666.

Still, if the end of the world really was coming, people were determined to enjoy themselves first. Pleasure, despite (or because of) the constant sense of mortality, dominated the age. Freed from the repressive shackles of the Commonwealth, those who could afford such luxuries wore gaudy, figure-enhancing and expensive new clothes and drank rich imported wine. New theatres were built for Londoners of all classes to go to see the suggestive new comedies whose authors often seemed to enjoy the same hard-living, hard-loving lives of their rake-hero protagonists. At home, people pursued illicit love affairs, safe in the knowledge that they would escape legal retribution; some even enjoyed carnal relations with members of their own sex, a risky move that nonetheless seemed tacitly sanctioned by the permissiveness of the time.

This was not, however, an age purely of indulgence and excess. Literature flourished, helped by the rise in mass printing and affordable books and pamphlets. People could buy witty and sometimes obscene poems written by a louche group of young aristocrats, many of whom had royal favour. They could also appreciate the emergence of politically and religiously engaged writers, from John Milton to John Bunyan, who eschewed the court (often by dint of being in prison) and wrote more weighty and ambitious works such as Paradise Lost and The Pilgrims Progress. The foundation of the Royal Society a few years earlier meant that serious matters of science and philosophy were central to the national conversation. Charles himself was a keen student and had his own private laboratory at Whitehall. Scientific innovators such as Robert Hooke formulated laws that would shape humanitys view of the physical universe for centuries thereafter; an apple fell from a tree in front of a twenty-three-year-old Isaac Newton. Even medicine evolved, albeit in a more limited fashion.

The poet John Dryden called 1666 an annus mirabilis, with the agenda of promoting himself to royal favour. The more sanguine John Evelyn described it as a year of nothing but prodigies in this nation: plague, war, fire, rains, tempest: comets. Beyond the clichs of orange-selling wenches and bewigged dandies lay a changing world that was as frightening and uncertain as it was seductive. The year 1666 stands at the dawn of a new age in which the Restoration reveals itself in all its tantalizing, contradictory aspects.

My first concerted experience of writing about the Restoration period came when I was researching Blazing Star, a biography of John Wilmot, 2nd earl of Rochester. Rochesters life to understate, a tumultuous affair was gripping material for any biographer, but the strange, beautiful and damaged time that he inhabited was every bit as compelling. Over and over again I was frustrated at having to jettison a fascinating story, or at not being able to follow an intriguing character in order to prevent the book becoming a slippery morass of sub-plots and background detail. When I finished writing