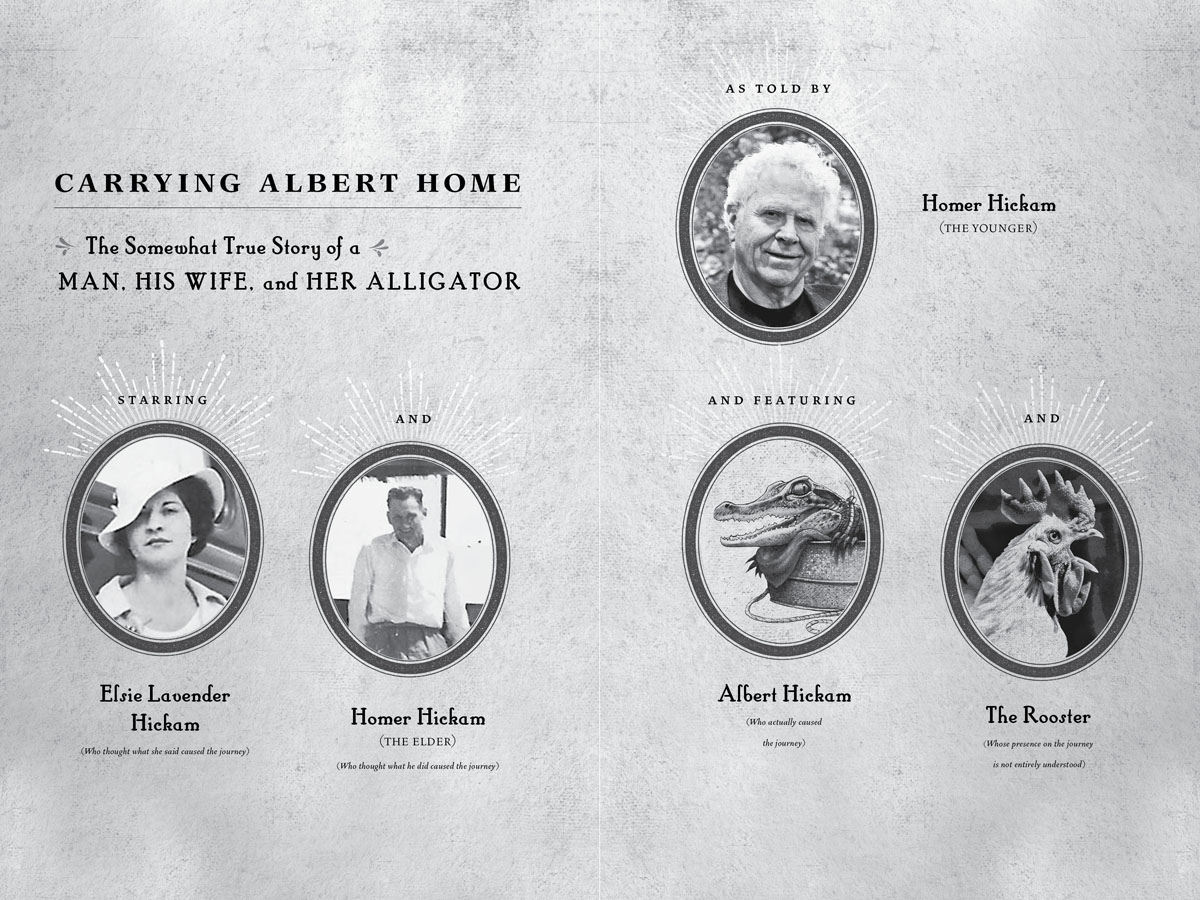

UNTIL MY MOTHER TOLD ME ABOUT ALBERT, I NEVER knew she and my father had undertaken an adventurous and dangerous journey to carry him home. I didnt know how they came to be married or what shaped them to become the people I knew. I also didnt know that my mother carried in her heart an unquenchable love for a man who became a famous Hollywood actor or that my father met that man after battling a mighty hurricane, not only in the tropics but in his soul. The story of Albert taught me these and many other things, not only about my parents but the life they gave me to live, and the lives we all live, even when we dont understand why.

The journey my parents took was in 1935, the sixth year of the Great Depression. At that time, a little more than one thousand people lived in Coalwood and, like my future parents, most of them were young marrieds who had grown up in the coalfields. Every day, as their fathers and grandfathers had done before them, the men got up and went to work in the mine where they tore at the raw coal with drills, explosives, picks, and shovels while the roof above them groaned and cracked and sometimes fell. Death happened often enough that a certain melancholy existed between the young men and women of the little West Virginia town when they made their daily farewells. Yet, for the company dollar and a company house, those farewells were made and the men trudged off to join the long line of miners, lunch buckets swinging and boots plodding, all heading for the deep, dark underground.

While their men toiled in the mine, the women of Coalwood were tasked with keeping their assigned company houses clean of the never-ending dust. Chuffing coal trains rumbled down tracks placed within feet of the houses, throwing up dense clouds of choking ebony powder that filtered inside no matter how tightly doors and windows were shut against it. Coalwoods people breathed dust with every breath and saw it rise in a gray mist when they walked the streets. It blossomed from their pillows when their tired heads were laid down and rose in a sparkling cloud when blankets were pushed aside after sleep. Each morning, the women got up and fought the dust, then got up the next day and fought it again after theyd sent their husbands to the mine to create more of it.

Raising the children was also left to the wives. This was at a time when scarlet fever, measles, influenza, typhus, and unidentified fevers routinely swept through the coalfields, killing weak and strong children alike. There were few families untouched by the loss of a child. The daily uncertainty for their husbands and children took its toll. Not too many years had to pass before the natural innocent sweetness of a young West Virginia girl was replaced by the tough, hard shell that characterized a woman of the coalfields.

This was the world as it was lived by Homer and Elsie Hickam, my parents before they were my parents. It was a world Homer accepted. It was a world Elsie hated.

But of course she did.

She had, after all, spent time in Florida.

Long after my parents made the journey that is told by this book, my brother Jim and I came along. Our childhoods were spent in Coalwood during the 1940s and 50s, when the town was growing older and some comforts such as paved roads and telephones had crept in. There was even television and, without it, I might have never heard about Albert. On the day I first heard about him, I was lying on the rug in our living room watching a rerun of the Walt Disney series about Davy Crockett. The show had made the frontiersman just about the most popular man in the United States, even more popular than President Eisenhower. In fact, there was scarcely a boy in America who didnt want to get one of Davys trademark coonskin caps, and that included me, although I never got one. Mom liked wild critters too much for that kind of cruel foolishness.

My mom walked in the living room when Davy and his pal Georgie Russell were riding horseback through the forest across our twenty-one-inch black-and-white screen. Georgie was singing about Davy and how he was the king of the wild frontier whod killed hisself a bar when he was only three. It was a catchy tune and I, like millions of kids across the country, knew every word. After a moment of silent watching, Mom said, I know him. He gave me Albert, and then turned and walked back into the kitchen.

I was focused on Davy and Georgie so it took a moment before Moms comment sank into my boyhood brain. When a commercial came on, I got up to look for her and found her in the kitchen. Mom? Did you say you knew somebody in the Davy Crockett show?

That fellow who was singing, she said while spooning a dollop of grease into a frying pan. Based on the lumpy slurry in a nearby bowl, I suspected we were having her famous fried potato cakes for supper.

You mean Georgie Russell? I asked.

No, Buddy Ebsen.

Whos Buddy Ebsen?

Hes the fellow who was singing on the television. He can dance better than he can sing and by a sight. I knew him in Florida when I lived with my rich Uncle Aubrey. When I married your father, Buddy sent me Albert as a wedding present.

I had never heard of Buddy or Albert but I had often heard of rich Uncle Aubrey. Mom always added the adjective rich to his name even though she said hed lost all his money in the stock market crash of 1929. Id seen a photograph of rich Uncle Aubrey. Round-faced, squinting into a bright sun while leaning on a golf club, rich Uncle Aubrey was wearing a newsboy Great Gatsby golf cap, a fancy sweater over an open-collared shirt, plus fours knickers, and brown and white saddle shoes. Behind him was a tiny aluminum trailer which apparently served as his home. It was my suspicion that rich Uncle Aubrey didnt need much money to be rich.

Seeking clarification, I asked, So... you know Georgie Russell?

If Buddy Ebsen is Georgie Russell, I surely do.

I stood there, my mouth open. Giddiness was near. I couldnt wait to tell the other Coalwood boys that my mom knew Georgie Russell, just one step removed from knowing Davy Crockett himself. I would surely be envied!

Albert stayed with us a couple of years, Mom went on. When we lived in the other house up the street in front of the substation. Before you and your brother were born.

Whos Albert? I asked.

For a moment, my mothers eyes softened. I never told you about Albert?

No, maam, I said, just as I heard the commercial end and the sound of flintlock muskets booming away. Davy Crockett was back in action. I cocked an ear in its direction.

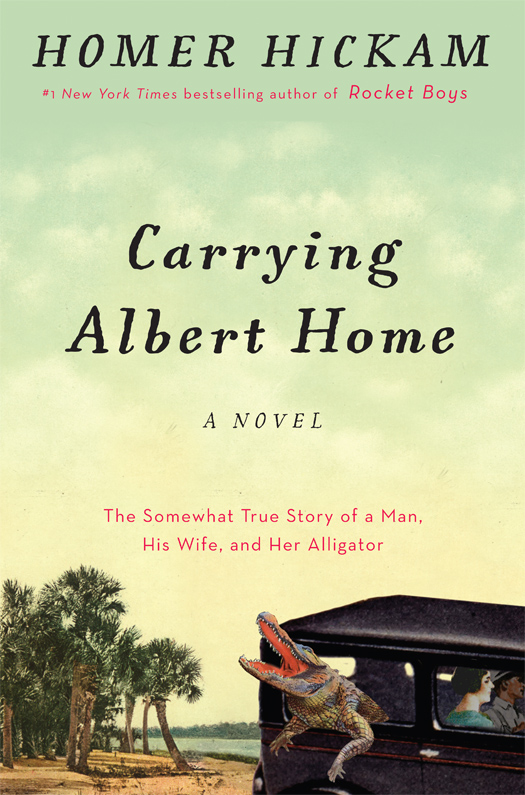

Seeing the pull of the television, she waved me off. Ill tell you about him later. Its kind of complicated. Your father and I... well, we carried him home. He was an alligator.

An alligator! I opened my mouth to ask more questions but she shook her head. Later, she said and got back to her potato cakes and I got back to Davy Crockett.

Over the years, Mom would do as she promised and tell me about carrying Albert home. At her prodding, Dad would even occasionally tell his side of it, too. As the tales were told, usually out of order and sometimes different from the last time Id heard them, they evolved into a lively but disconnected and surely mythical story of a young couple who, along with a special alligator (and for no apparent reason, a rooster), had the adventure of a lifetime while heading ever south beneath what I imagined was a landscape artists golden sun and a poets quicksilver moon.