Tastemaker

Monica Penick

Tastemaker

Elizabeth Gordon, House Beautiful, and the Postwar American Home

Copyright 2017 by Monica Penick.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

yalebooks.com/art

Designed by Yve Ludwig

Set in Chronicle Text and Avenir by Yve Ludwig

Printed in China by Regent Publishing Services Limited

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016940999

ISBN 978-0-300-22176-3

eISBN 978-0-300-22845-8

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Preface

When I began the long adventure of writing Tastemaker, I was interested in the evolution of the postwar American house, with its multiplicity of modern forms and cultural meanings. I was fascinated by the range of characters involved: architects, designers, craftsmen, builders, manufacturers, retailers, and real estate developers who had left their mark, however distinct or faint, on the American landscape. But as I workedin a subject area and time period that were still virtually undiscoveredI began to look beyond what I thought was the heart of the story, beyond the house itself, beyond its designers, beyond its makers. What I found there, on the periphery, was an entirely new plot and a new cast of characters. Chief among them were the consumers (most often the American family) for whom the postwar house was built, and the popular home or shelter magazines that promoted and indeed sold the idea of the postwar house and its domestic trappings to the public.

The question then became not what happened to the American house in the two decades that followed the Second World War, but who (or what) really made that something happen? This opened still another broad, cultural question: Why do Americans like what they like, buy what they buy, and build what they build?

This was not, of course, a new question. In the United States, questions of consumer desire, taste, and choice were posed as early as the 1920s by professionals engaged in the emerging field of consumer study and market research. Among the most influential were two figures who appear briefly in this book, Edward Bernays and Christine McGaffey Frederick. Their lines of inquiry took a variety of forms and served many purposes. The goal was generally threefold: to investigate consumers needs, wants, and actions; to test new products against consumer interest; and (eventually) to use this feedback to inform the design, production, sales, and consumption of products.

The protagonist of this book, former House Beautiful editor-in-chief Elizabeth Gordon, was equally engaged in the quest to understand and influence consumer choice, specifically in the realm of domestic architecture and design. She was fascinated by American tasteor as she put it, why you like what you like, and what you are probably going to like in the future. She asked this very question, most directly in 1946, from the vantage point of a shelter magazine editor in need of perspective and some monthly content; I asked it, decades later, as a historian curious about how Gordon answered, and what her experience might tell us about the process of taste formation, design consumption, design production, and design mediation that remains in place even today within contemporary shelter magazines such as Dwell, or multimedia outlets such as HGTV.

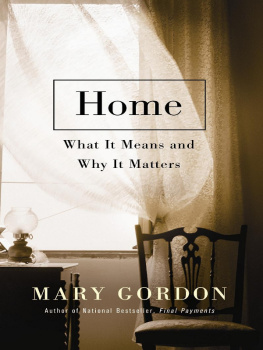

Elizabeth Gordon at Taliesin West, Scottsdale, Arizona, ca. 1946.

Gordons questioning, and my own that followed, suggested an alternative way to unpack the history of the postwar American house. Perhaps architect George Nelson, writing in 1948, saw it most clearly: Most of what happens to architecture is out of the hands of the architects.contemporary design discourse, social attitudes, consumer power (both in terms of buying practices and market influence), personal taste, individual identity, and an emerging sense of a collective Americanness. I argue here that the shelter press, led by powerful editors such as Gordon, informed and influenced all of these forces.

What follows is a design history, in the inclusive if still-evolving meaning of that term: it is the study of postwar American design, with culture, politics, and economics as backdrop; it is an architectural history, with architects and houses as star players; it is a critical biography, with a magazine editor as protagonist; and it is a study of a creative process, with print representation, cross-media methods, and editorial tactics as evidence. In the broadest sense, though, this is a story about influence.

From her offices on Madison Avenue, Elizabeth Gordon navigated a design revolution that spanned the hopeful (if restrained) war years, the optimistic postwar period, and the anxious Cold War decades. Her story, set against this changing historical backdrop, pivots at significant moments when Gordon responded, with lightning speed, to this shifting world. The narrative arc of this book is possible, in part, because Gordons own editorials traversed a national crisis of culture, politics, and economicsand she embedded her editorial campaigns and critiques within this larger contemporary context.

Gordons story is fascinating and at moments truly theatrical because she worked so many angles: she was a reporter, editor, advocate, critic, trendsetter, and tastemaker. She worked on behalf of the American public (which paralleled her magazines commercial interest) to forge a common cause for good design. In this struggle, she did not work alone. She united consumers, designers, manufacturers, and retailers in her cause. She navigated and bridged all four worlds, and for many years held a comfortable place on the sidelines of design discourse and practice.

This all changed in 1953. Her scandalous editorial The Threat to the Next America was the watershed moment. The Threat episode (which I recount in ) is the moment for which she was both celebrated and detested. But this is only a small part of her story, and the only chapter that design history has, up to now, recorded. The rest of her story, told for the first time in this book, spans two full decades and scores of pioneering editorial projects.

Because Gordon became such a galvanizing figure, her influence on American taste and American designand, with it, the role of the shelter press that she representshas been difficult to assess critically. With this book, I have tried to do both.

Gordons editorship and her role within American design offer a compelling case study with larger implications for the history of American architecture and design. First, while many scholars have examined the contributions of individual architects and designers, few have assessed those of the professionals who popularized and sold design to the American public. Gordon was one of those figures, significant because she exerted influence from a position often considered peripheral, and from a popular platform often deemed inconsequential by some architects, historians, and critics of her time and ours. Perhaps more remarkably, Gordon often worked in opposition (sometimes with open antagonism) to the dominant cultural institutions and professional journals that historically controlled matters of design taste and design production. This book, then, broadens our understanding of the power players who have shaped the world of architecture and design.

Next page