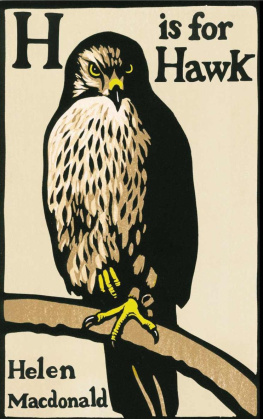

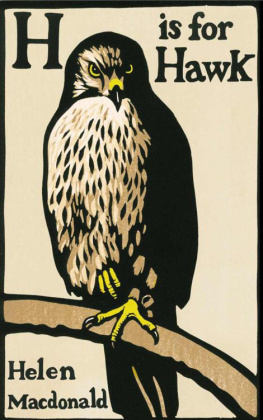

H Is for Hawk

Falcon

Shalers Fish

Copyright 2020 by Helen Macdonald

Jacket design by Suzanne Dean

Jacket photograph Chris Wormell

Some of these pieces have appeared in different form in the New York Times Magazine, New Statesman and elsewhere.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or permissions@groveatlantic.com.

First published in the United Kingdom in 2020 by Jonathan Cape

First Grove Atlantic eBook edition: August 2020

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

eISBN 978-0-8021-4669-4

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

Contents

Back in the sixteenth century, a curious craze began to spread through the halls, palaces and houses of Europe. It was a type of collection kept often in ornate wooden cases, and it was known as a Wunderkammer, a Cabinet of Curiosities, although the direct translation from the German captures better its purpose: cabinet of wonders. It was expected that people should pick up and handle the objects in these cases; feel their textures, their weights, their particular strangenesses. Nothing was kept behind glass, as in a modern museum or gallery. More importantly, perhaps, neither were these collections organised according to the museological classifications of today. Wunderkammern held natural and artificial things together on shelves in close conjunction: pieces of coral; fossils; ethnographic artefacts; cloaks; miniature paintings; musical instruments; mirrors; preserved specimens of birds and fish; insects; rocks; feathers. The wonder these collections kindled came in part from the ways in which their disparate contents spoke to one another of their similarities and differences in form, their beauties and manifest obscurities. I hope that this book works a little like a Wunderkammer. It is full of strange things and it is concerned with the quality of wonder.

Someone once told me that every writer has a subject that underlies everything they write. It can be love or death, betrayal or belonging, home or hope or exile. I choose to think that my subject is love, and most specifically love for the glittering world of non-human life around us. Before I was a writer I was a historian of science, which was an eye-opening occupation. We tend to think of science as unalloyed, objective truth, but of course the questions it has asked of the world have quietly and often invisibly been inflected by history, culture and society. Working as a historian of science revealed to me how we have always unconsciously and inevitably viewed the natural world as a mirror of ourselves, reflecting our own world-view and our own needs, thoughts and hopes. Many of the essays here are exercises in interrogating such human ascriptions and assumptions. Most of all I hope my work is about a thing that seems to me of the deepest possible importance in our present-day historical moment: finding ways to recognise and love difference. The attempt to see through eyes that are not your own. To understand that your way of looking at the world is not the only one. To think what it might mean to love those that are not like you. To rejoice in the complexity of things.

Science encourages us to reflect upon the size of our lives in relation to the vastness of the universe or the bewildering multitudes of microbes that exist inside our bodies. And it reveals to us a planet that is beautifully and insistently not human. It was science that taught me how the flights of tens of millions of migrating birds across Europe and Africa, lines on the map drawn in lines of feather and starlight and bone, are stranger and more astonishing than I could ever have imagined, for these creatures navigate by visualising the Earths magnetic field through detecting quantum entanglement taking place in the receptor cells of their eyes. What science does is what I would like more literature to do too: show us that we are living in an exquisitely complicated world that is not all about us. It does not belong to us alone. It never has done.

These are terrible times for the environment. Now more than ever before, we need to look long and hard at how we view and interact with the natural world. Were living through the worlds sixth great extinction, one caused by us. The landscapes around us grow emptier and quieter each passing year. We need hard science to establish the rate and scale of these declines, to work out why it is occurring and what mitigation strategies can be brought into play. But we need literature, too; we need to communicate what the losses mean. I think of the wood warbler, a small citrus-coloured bird fast disappearing from British forests. It is one thing to show the statistical facts about this species decline. It is another thing to communicate to people what wood warblers are, and what that loss means, when your experience of a wood that is made of light and leaves and song becomes something less complex, less magical, just less, once the warblers have gone. Literature can teach us the qualitative texture of the world. And we need it to. We need to communicate the value of things, so that more of us might fight to save them.

When I was small, I decided I wanted to be a naturalist. And so I slowly amassed a nature collection, and arranged it across my bedroom sills and shelves as a visible display of all the small expertises Id gathered from the pages of books. There were galls, feathers, seeds, pine cones, loose single wings of small tortoiseshells or peacock butterflies picked from spiders webs; the severed wings of dead birds, spread and pinned on to cardboard to dry; the skulls of small creatures; pellets tawny owl, barn owl, kestrel and old birds nests. One was a chaffinch nest I could balance in the palm of my hand, a thing of horsehair and moss, pale scabs of lichen and moulted pigeon feathers; another was a song-thrush nest woven of straw and soft twigs with a flaking inner cup moulded from clay. But those nests never felt as if they fitted with the rest of my beloved collection. It wasnt that they conjured the passing of time, of birds flown, of life in death. Those intuitions are something you learn to feel much later in life. It was partly because they made me feel an emotion I couldnt name, and mostly because I felt I shouldnt possess them at all. Nests were all about eggs, and eggs were something I knew I shouldnt ever collect. Even when I came across a white half-shell picked free of twigs by a pigeon and dropped on a lawn, a moral imperative stilled my hand. I could never bring myself to take it home.

Naturalists in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries routinely collected birds eggs, and most children who grew up in semi-rural or rural surroundings in the 1940s and 50s have done it too. We only used to take one from each nest, a woman friend told me, abashed. Everyone did it. Its simply an accident of history that people two decades older than me have nature knowledges I do not possess. So many of them, having spent their childhoods birds-nesting, still see a furze bush and think,

Next page