Contents

About the Book

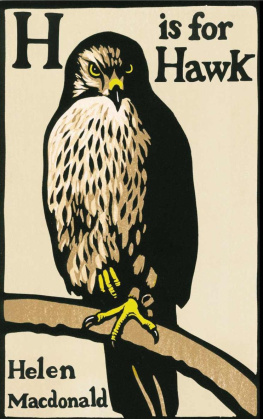

In real life, goshawks resemble sparrowhawks the way leopards resemble housecats. Bigger, yes. But bulkier, bloodier, deadlier, scarier, and much, much harder to see. Birds of deep woodland, not gardens, theyre the birdwatchers dark grail.

As a child Helen Macdonald was determined to become a falconer. She learned the arcane terminology and read all the classic books, including T. H. Whites tortured masterpiece, The Goshawk , which describes Whites struggle to train a hawk as a spiritual contest.

When her father dies and she is knocked sideways by grief, she becomes obsessed with the idea of training her own goshawk. She buys Mabel for 800 on a Scottish quayside and takes her home to Cambridge. Then she fills the freezer with hawk food and unplugs the phone, ready to embark on the long, strange business of trying to train this wildest of animals.

To train a hawk you must watch it like a hawk, and so gain the ability to predict what it will do next. Eventually you dont see the hawks body language at all. You seem to feel what it feels. The hawks apprehension becomes your own. As the days passed and I put myself in the hawks wild mind to tame her, my humanity was burning away.

Destined to be a classic of nature writing, H is for Hawk is a record of a spiritual journey an unflinchingly honest account of Macdonalds struggle with grief during the difficult process of the hawks taming and her own untaming. At the same time, its a kaleidoscopic biography of the brilliant and troubled novelist T. H. White, best known for The Once and Future King . Its a book about memory, nature and nation, and how it might be possible to try to reconcile death with life and love.

About the Author

Helen Macdonald is a writer, poet, illustrator, historian and affiliate at the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge. Her books include Falcon (2006) and Shalers Fish (2001).

ALSO BY HELEN MACDONALD

Shalers Fish

Falcon

To my family

H is for Hawk

Helen Macdonald

PART I

Patience

FORTY-FIVE MINUTES north-east of Cambridge is a landscape Ive come to love very much indeed. Its where wet fen gives way to parched sand. Its a land of twisted pine trees, burned-out cars, shotgun-peppered road signs and US Air Force bases. There are ghosts here: houses crumble inside numbered blocks of pine forestry. There are spaces built for air-delivered nukes inside grassy tumuli behind twelve-foot fences, tattoo parlours and US Air Force golf courses. In spring its a riot of noise: constant plane traffic, gas-guns over pea fields, woodlarks and jet engines. Its called the Brecklands the broken lands and its where I ended up that morning, seven years ago, in early spring, on a trip I hadnt planned at all. At five in the morning Id been staring at a square of streetlight on the ceiling, listening to a couple of late party-leavers chatting on the pavement outside. I felt odd: overtired, overwrought, unpleasantly like my brain had been removed and my skull stuffed with something like microwaved aluminium foil, dinted, charred and shorting with sparks. Nnngh. Must get out , I thought, throwing back the covers. Out! I pulled on jeans, boots and a jumper, scalded my mouth with burned coffee, and it was only when my frozen, ancient Volkswagen and I were halfway down the A14 that I worked out where I was going, and why. Out there, beyond the foggy windscreen and white lines, was the forest. The broken forest. Thats where I was headed. To see goshawks.

I knew it would be hard. Goshawks are hard. Have you ever seen a hawk catch a bird in your back garden? Ive not, but I know its happened. Ive found evidence. Out on the patio flagstones, sometimes, tiny fragments: a little, insect-like songbird leg, with a foot clenched tight where the sinews have pulled it; or even more gruesomely a disarticulated beak, a house-sparrow beak top, or bottom, a little conical bead of blushed gunmetal, slightly translucent, with a few faint maxillary feathers adhering to it. But maybe you have: maybe youve glanced out of the window and seen there, on the lawn, a bloody great hawk murdering a pigeon, or a blackbird, or a magpie, and it looks the hugest, most impressive piece of wildness youve ever seen, like someones tipped a snow leopard into your kitchen and you find it eating the cat. Ive had people rush up to me in the supermarket, or in the library, and say, eyes huge, I saw a hawk catch a bird in my back garden this morning! And Im just about to open my mouth and say, Sparrowhawk! and they say, I looked in the bird book. It was a goshawk . But it never is; the books dont work. When its fighting a pigeon on your lawn a hawk becomes much larger than life, and bird-book illustrations never match the memory. Heres the sparrowhawk. Its grey, with a black and white barred front, yellow eyes and a long tail. Next to it is the goshawk. This one is also grey, with a black and white barred front, yellow eyes and a long tail. You think, Hmm . You read the description. Sparrowhawk: twelve to sixteen inches long. Goshawk: nineteen to twenty-four inches. There. It was huge. It must be a goshawk. They look identical. Goshawks are bigger, thats all. Just bigger.

No. In real life, goshawks resemble sparrowhawks the way leopards resemble housecats. Bigger, yes. But bulkier, bloodier, deadlier, scarier and much, much harder to see. Birds of deep woodland, not gardens, theyre the birdwatchers dark grail. You might spend a week in a forest full of gosses and never see one, just traces of their presence. A sudden hush, followed by the calls of terrified woodland birds, and a sense of something moving just beyond vision. Perhaps youll find a half-eaten pigeon sprawled in a burst of white feathers on the forest floor. Or you might be lucky: walking in a foggy ride at dawn youll turn your head and catch a split-second glimpse of a bird hurtling past and away, huge taloned feet held loosely clenched, eyes set on a distant target. A split second that stamps the image indelibly on your brain and leaves you hungry for more. Looking for goshawks is like looking for grace: it comes, but not often, and you dont get to say when or how. But you have a slightly better chance on still, clear mornings in early spring, because thats when goshawks eschew their world under the trees to court each other in the open sky. That was what I was hoping to see.

I slammed the rusting door, and set off with my binoculars through a forest washed pewter with frost. Pieces of this place had disappeared since I was last here. I found squares of wrecked ground; clear-cut, broken acres with torn roots and drying needles strewn in the sand. Clearings. Thats what I needed. Slowly my brain righted itself into spaces unused for months. For so long Id been living in libraries and college rooms, frowning at screens, marking essays, chasing down academic references. This was a different kind of hunt. Here I was a different animal. Have you ever watched a deer walking out from cover? They step, stop, and stay, motionless, nose to the air, looking and smelling. A nervous twitch might run down their flanks. And then, reassured that all is safe, they ankle their way out of the brush to graze. That morning, I felt like the deer. Not that I was sniffing the air, or standing in fear but like the deer, I was in the grip of very old and emotional ways of moving through a landscape, experiencing forms of attention and deportment beyond conscious control. Something inside me ordered me how and where to step without me knowing much about it. It might be a million years of evolution, it might be intuition, but on my goshawk hunt I feel tense when Im walking or standing in sunlight, find myself unconsciously edging towards broken light, or slipping into the narrow, cold shadows along the wide breaks between pine stands. I flinch if I hear a jay calling, or a crows rolling, angry alarum. Both of these things could mean either Warning, human! or Warning, goshawk! And that morning I was trying to find one by hiding the other. Those old ghostly intuitions that have tied sinew and soul together for millennia had taken over, were doing their thing, making me feel uncomfortable in bright sunlight, uneasy on the wrong side of a ridge, somehow required to walk over the back of a bleached rise of grasses to get to something on the other side: which turned out to be a pond. Small birds rose up in clouds from the ponds edge: chaffinches, bramblings, a flock of long-tailed tits that caught in willow branches like animated cotton buds.

Next page