In loving memory of Joanne Page

When eating a fruit, think of the person who planted the tree.

VIETNAMESE PROVERB

Each autumn a dozen little red apples hung on one of its branches like a line of poetry in a foreign language.

EDWARD THOMAS

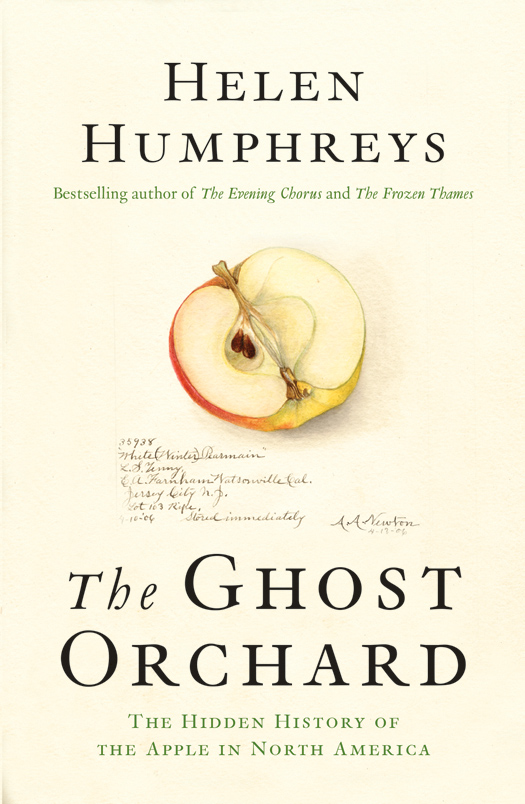

L ast fall I was eating wild apples, and a close friend of mine was slowly dying. I was thinking a lot about death and friendship, and overtop of that was the sweet, dense taste of the White Winter Pearmain: the crisp of its flesh, a juicy surprise, each time I bit into it.

The apple tree stood beside a log cabin. The tree is dead now, killed by the harsh winter, its lace of dry branches a filigree through which I can see the green spring trees plumping the field edge when I come here to walk the dog.

The cabin is long deserted, its windows smashed out by weekend partiers and the loft now inhabited by a colony of raccoons. The teenagers and the raccoons have treated the house in much the same waydestroying the walls and shitting in the corners. The raccoons upstairs, the teenagers down. When I drove out there tonight, the raccoons tried to warn me away from the building with a chorus of yelps.

But Im not interested in the house. Its the tree I came for.

Just last year, when the tree was still alive, I ate its apples all autumn. They were yellow-skinned, with a faint pink blush on one side where the sun had touched them. They were late apples, ripening in October and still edible into December. They also had an extraordinary tastecrisp and juicy with an underlay of pear and honey.

The tree was mature but not ancient, the last holdout from an old orchard, perhaps, or planted by the former owner of the property. There had probably once been other apple trees nearbyearlier-blooming ones so that the fruit could be eaten and cooked from late summer until Christmas. A late apple will sometimes keep in storage right through winter.

The White Winter Pearmain is thought to have come from Rome, but it was first documented in Norfolk, England, in AD 1200. From there it moved to America in the late eighteenth century, and while it is not a popular heritage apple today, it is still being grown and is prized for its late fruiting and for its taste. Because the apple has a hint of pearhence the pearmain in its nameit has a complex flavour, and it is this complexity, this overlapping of apple and pear in the same fruit, that has led to it being called the best-tasting apple in the world.

When I was growing up on the outskirts of Toronto, there were rogue apple trees in all the nearby fields. We climbed them and made forts in them and pelted other children with the hard unripe fruit. The scent in autumn in the fields was the scent of rotting apples and the sound was the buzz of wasps over the soft, sticky pulp on the ground. There was a particularly old apple tree up the street from my house. Its low branches made it easy to climb, and my friends and I hauled up wood and nails and made a series of platforms in the tree, using an old tire and a rope as a makeshift elevator to move us and the building supplies up and down. In my melancholic teenage years, I would sit in the branches among the apples, thinking my gloomy thoughts and listening to the wind rustle the leaves around my perch.

Back then, I took the fact of the apple trees at the edge of our neighbourhood for granted. Now, I realize that the immense size of that one tree I used to climb probably meant it was at least a century oldwhich is ancient for an apple tree. I wish I had been interested enough at the time to think of investigating what variety of apple tree it was, because all the varieties have a story attached to them, and because, in the nineteenth-century heyday of apples, there were upwards of seventeen thousand different varieties in North American orchards. Today there are fewer than a hundred varieties grown commercially, and often less than a dozen varieties for sale in our grocery stores. When we think of apples, we tend to think of Granny Smith, Gala, Red Delicious, Honeycrisp, and perhaps something with a little more exoticism, like Ginger Gold or Orange Pippin. When we think of tales about apples, we think primarily of the over-mythologized Johnny Appleseed.

This is what the seventeen thousand different varieties have been reduced to.

There must be more to the story of the apple than the history that is so readily available. There must be a way to describesimply and beautifullythe taste of an apple.

The presence of death brings life into sharper focus, makes some things more important and others less so. I couldnt stop my friends death, or fight against it. I stood out by the log cabin and the dead tree that night and thought that what I could do was make a journey alongside Joannea journey that was about something life-affirming, something as basic and fundamental as an apple. I could take my curiosity about the White Winter Pearmain and use it as a portal to examine the lost history of some of the lost apples.

W hat makes apples so interesting is that like human beings, they are individuals, and their history has paralleled our history.

The apple is a member of the rose family. It originated some 4.5 million years ago in Kazakhstan, where, until the latter part of the twentieth century, there were still large forests of apple trees growing wild in the countryside. The fruit made its way to Europe via trade routes and was brought from Europe to North America by settlers in the seventeenth century.

Apples are not indigenous to North America. They were brought over by the European settlers who arrived on the continent in the early 1600s. An orchard was essential to the survival of the incomers because apples were hearty and could provide sustenance throughout the long winter months. In fact, at the beginning of the 1800s, America enacted a law saying that homesteaders had to plant an orchard of at least fifty apple trees during their first year of settlement. This law gave rise to many plant nurseries, established to furnish the settlers with the young trees they needed.

The recorded history of the apple in North America is the history of white settlement during the nineteenth century. It is the history of plant nurseries and cider orchards and fruit catalogues, as well as the slightly mad figure of Johnny Appleseed (John Chapman), traversing the countryside with his sack of seeds, planting trees for cider orchards and opening seedling nurseries to supply the settlers with young trees, called whips, so they could grow their own.

Apples can be propagated from seed, but the resulting tree will probably not resemble the tree from which the seed was taken. This is because each blossom on an apple tree is likely being visited by a different pollinator. So the bee that pollinates blossom A doesnt necessarily visit blossom B, and that bee also carries on its body pollen from other apple trees it has visited. As a result, the mix in each individual apple is different and distinct, so the seeds of each apple on any given tree will be 50 percent from the tree of origin and 50 percent from another apple tree, perhaps even one of a different type. The only way to keep apples uniform is to graft on to a rootstock, and this is the method by which all apples are commercially grown. It was also the method used by early European growers and by North American settlers to produce reliable apple varieties.

When apples are planted from seed, without grafting, no two trees will be exactly alike and often the fruit will be inedible spitters. But even an apple thats no good for eating is usually fine for drinking, and orchards of ungrafted apples were often used as cider orchards. John Chapman, in giving and selling ungrafted apple seedlings, was supplying settlers with the makings for cider orchards, and much of colonial American life was probably experienced through a heavy alcoholic haze (which, quite frankly, might have made it more bearable).