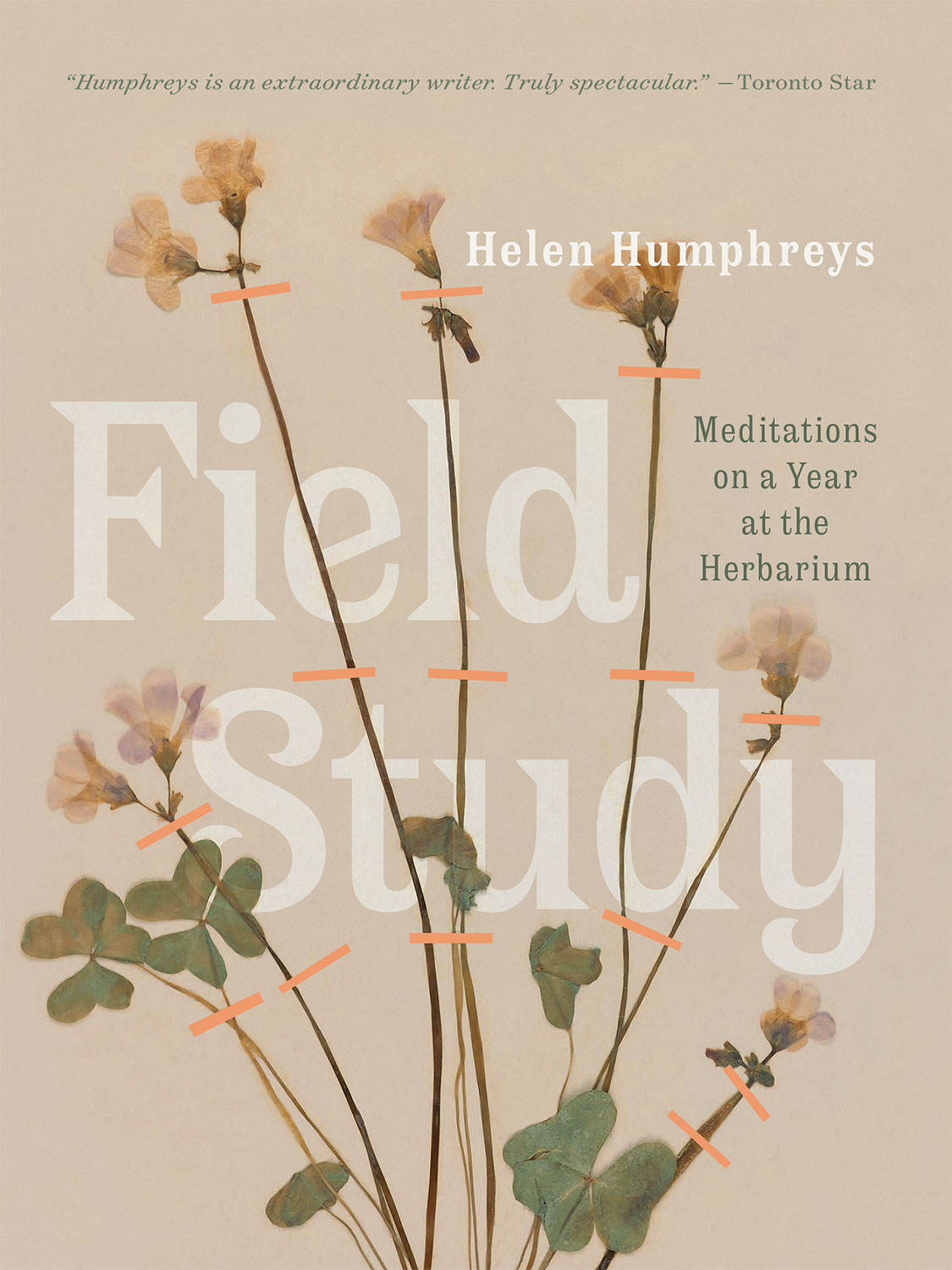

Helen Humphreys - Field study : meditations on a year at the herbarium

Here you can read online Helen Humphreys - Field study : meditations on a year at the herbarium full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Field study : meditations on a year at the herbarium

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Field study : meditations on a year at the herbarium: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Field study : meditations on a year at the herbarium" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Field study : meditations on a year at the herbarium — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Field study : meditations on a year at the herbarium" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Meditations on a Year at the Herbarium

Helen Humphreys

This book was researched and written on the traditional territory of the Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee peoples. I am grateful for their long and vital relationship with the plant life that inhabits this region.

For KW

Herbarium specimens are the physical vouchers for the world as it was.

Deb Metsger, curator of the Royal Ontario Museum

Green Plant Herbarium

There are days we live as if death were nowhere in the background; from joy to joy to joy, from wing to wing, from blossom to blossom to impossible blossom, to sweet impossible blossom.

Li-Young Lee, From Blossoms

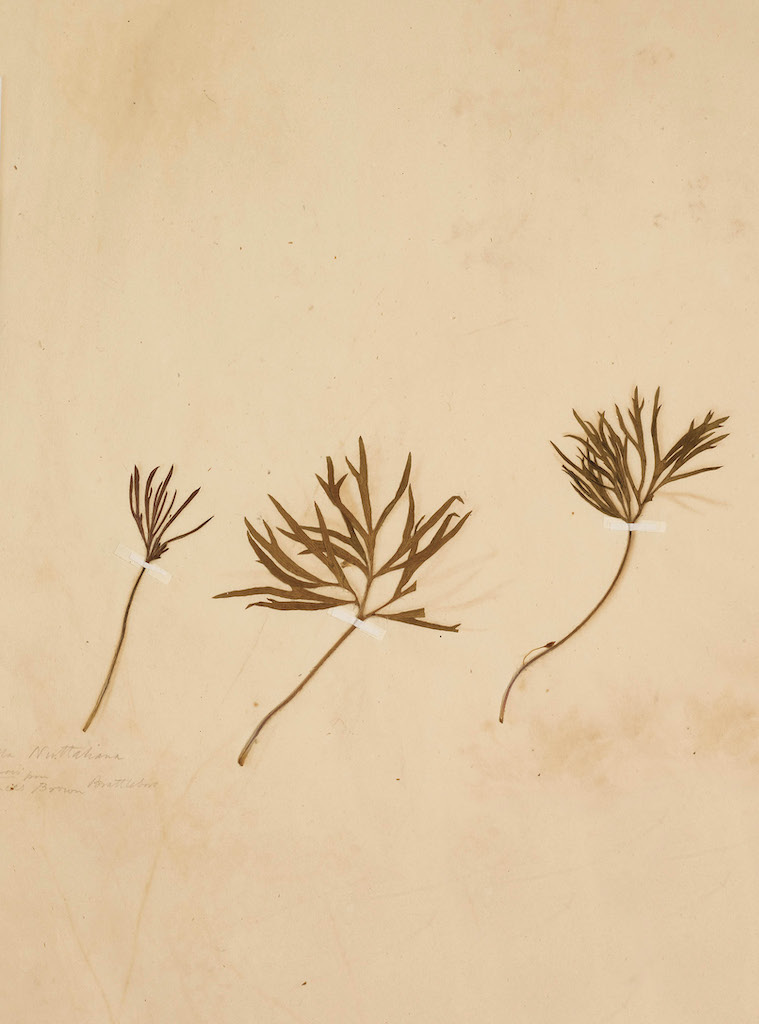

American Pasqueflower

(Pulsatilla nuttalliana)

Henry David Thoreau

The autumn leaves floating down over the field look like brightly coloured birds falling to earth. We have just left the pine wood and are on the path that my walking companion calls Carnage Alley, because there are often feathers, or blood, or bits of dead animal on this route. The victims of coyotes, perhaps, or the owls that hunt above this field at dusk. Easier to catch something in the open than in the tangled wrack of forest trees, and even now there is a northern harrier skimming the tops of the asters and milkweed. We always consider it lucky to see the harrier, so we stop to watch its low, silent glide. It seems otherworldly, an owls head on a hawks body, the elegant drift of its hunger.

This place of woods and meadow and marsh is paradise. My paradise. Where I walk every day, all through the seasons. It always seems to be teeming with wildlife and plant life, but things have changed even in the handful of years I have been coming here. Now there are deer ticks on all the forest paths and in the open fields. The toxic wild parsnip is creeping through the meadows, and an invasive feathery reed, phragmites, is choking out the wetlands. The bobolinks and meadowlarks, who used to be plentiful every summer, are now virtually non-existent.

Habitat loss, pollution, climate change, human overpopulation and encroachment these are some of the main reasons for the decline and changes to ecosystems. Much of the damage is irreversible, and the prognosis for the future is grim. And yet, I believe there is still a profound need within human beings to connect to the natural world.

How to reconcile these two things?

Increasingly, this morning walk I take through the woods and fields with my dog and a friend has become crucial to my physical and mental health. Without it, I have difficulty handling all the stresses of this world, and all the losses that have occurred in my own life.

I am interested in exploring this relationship, to write from a place that doesnt look away from the environmental changes wrought by humankind and that also celebrates the connections that still exist between people and nature.

To do this, I have chosen to concentrate on the phenomenon of the herbarium. These libraries of dried plant specimens some hundreds of years old seem the perfect crucible in which to examine the intersection of human beings and the natural world through time. Each herbarium specimen is mounted on a sheet of paper with a label affixed by the collector, providing details of the plant and the location where it was found, but also including information about the person who preserved the plant. In this way the herbarium becomes a place, a landscape if you will, where the experience of people connecting with nature is revealed. I cannot think of another place where it is possible to look into the past and see the moment an orchid was plucked from the forest floor or a willow frond was cut from a branch. A visit to the herbarium is an exquisite kind of time travel. And by learning more about the intersection of people and nature in the past, I hope to gain some understanding of where we can go from here.

Winter

The Herbarium

Specimen

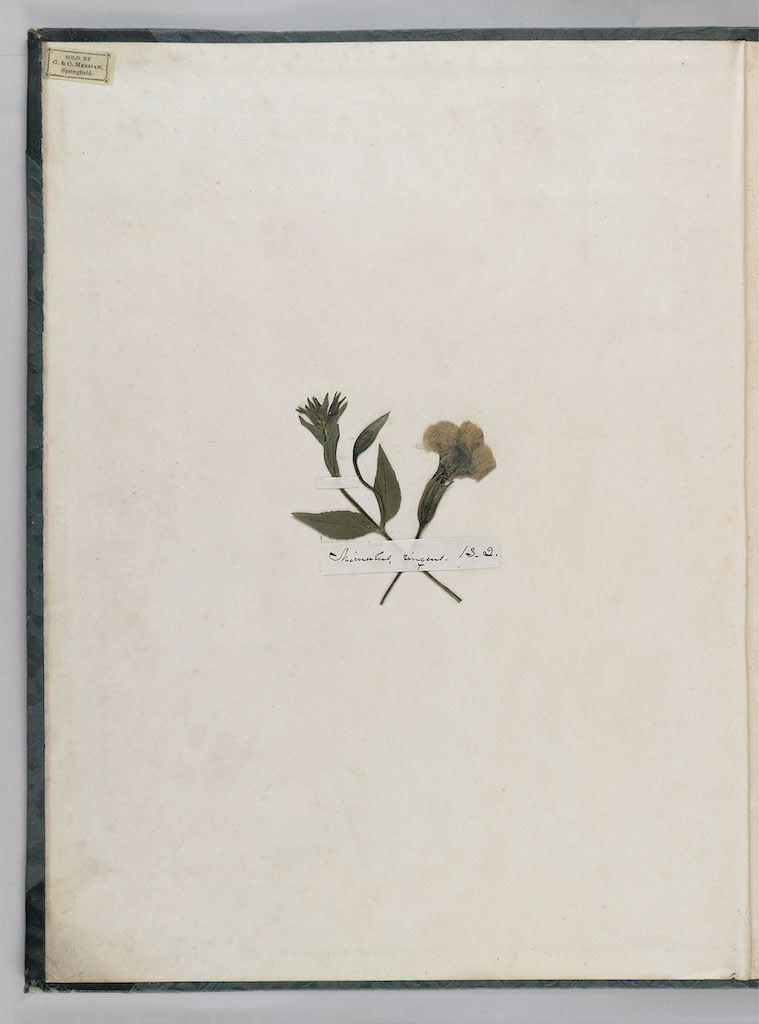

Allegheny Monkeyflower

(Mimulus ringens)

Emily Dickinson

The road to my particular herbarium the Fowler Herbarium winds through forest, twisting like a river, each turn revealing something new and surprising: a rafter of wild turkeys in the woods; deer browsing on the underbrush; a glittering, icy pond fringed with rushes; and, once, a fox nose down, snouting the snowy furrows of a winter field.

This herbarium originated in the late 1800s under the auspices of the Reverend James Fowler and was once housed in Queens University in Kingston, Ontario. It now has its own building at the site of the universitys biological station on the edge of Opinicon Lake: a climate-controlled, metal-clad structure that houses over 140,000 dried plant specimens. I mean to look at each and every one of them.

A couple of hundred years ago, it seems as if literally everyone picked and pressed flowers and plants and made a herbarium. Thoreau had one, as did Emily Dickinson. Botanizing was a popular settler pastime in the nineteenth century, both on a professional and amateur level, with lots of cross-pollination between the two groups. One aspect of colonization was a feverish desire by the incomers to catalogue the flora and fauna of North America, and since the tools required for botanizing were few a notebook and pencil, magnifying glass, and specimen bag it became available to rich and poor alike. The abundance of wilderness and the minimal equipment required to explore it was coupled with the notion in the mid- to late 1800s of self-improvement through acquired knowledge. Many people who did not have a formal education were motivated to learn more about the fields and forests that surrounded their towns and villages as a way to better themselves, and in doing so, perhaps better their situation in the larger world. Unfortunately, many plants, including the familiar Ladys Slipper Orchid (Cypripedium calceolus) were driven to the edge of extinction by enthusiastic plant hunters and collectors.

Ladys Slipper Orchid

(Cypripedium calceolus)

Emily Dickinson

Before field guides, plant specimens were mailed to other botanizers for identification. Many of these experts were men and women with no formal scientific training, people who were simply passionate about a particular species of plant and had become an authority on it. In the twentieth century, this amateur-professional alliance ceded to a model of science first, and the opinions of amateur botanists many of whom had become leading experts in the field were no longer sought out by the qualified scientists. When these amateur experts died, their collections were distributed among the many institutional herbaria, or destroyed. As a result, the present-day herbaria housed in universities and museums are composed of specimens from a multitude of both amateur and professional collectors, from all over the world. The herbarium has become a memorial to a kind of democracy that no longer exists in the same way in the scientific world, even with the advent of citizen science.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Field study : meditations on a year at the herbarium»

Look at similar books to Field study : meditations on a year at the herbarium. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Field study : meditations on a year at the herbarium and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.