Barbara M. Thiers - Herbarium: The Quest to Preserve & Classify the World’s Plants

Here you can read online Barbara M. Thiers - Herbarium: The Quest to Preserve & Classify the World’s Plants full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Workman Publishing, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Herbarium: The Quest to Preserve & Classify the World’s Plants

- Author:

- Publisher:Workman Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Herbarium: The Quest to Preserve & Classify the World’s Plants: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Herbarium: The Quest to Preserve & Classify the World’s Plants" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Herbarium: The Quest to Preserve & Classify the World’s Plants — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Herbarium: The Quest to Preserve & Classify the World’s Plants" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Herbarium

The Quest to Preserve &

Classify the Worlds Plants

Barbara M. Thiers

For my parents, Ellen J. and Harry D. Thiers,

and my mentor, Patricia K. Holmgren

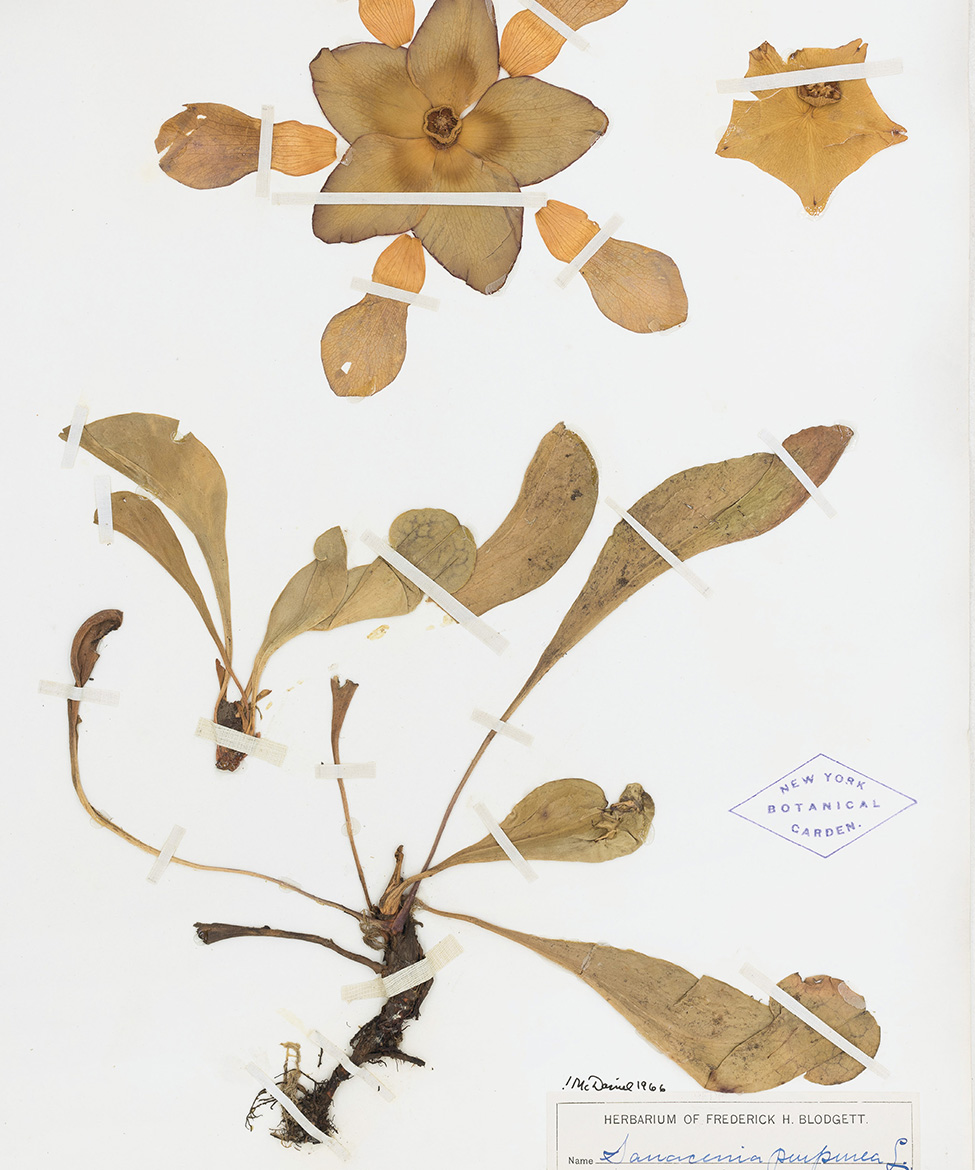

An herbarium specimen of Sarracenia purpurea (common pitcherplant).

Ive been around herbaria all my life. My father was founder and curator for 40 years of the herbarium at San Francisco State University (now the Harry D. Thiers Herbarium). In addition to teaching, he poured his considerable curiosity and energy into documenting the fungi, primarily, but also the bryophytes (i.e., mosses and liverworts) and lichens of California. My childhood weekends were spent either on field trips or in the herbarium, where I could earn some pocket money by helping my dad with his specimens. I have fond memories of Sunday afternoons spent gluing specimen labels to boxes as my dad typed them while we listened to Giants baseball games on the radio. As a teenager, I wanted nothing to do with the herbarium, or my parents for that matter, but eventually, in the middle of my college years, I found my way back. I discovered that I too wanted to participate in the great adventure of documenting plant and fungal lifeand to join my dad and his passionate, sometimes eccentric band of students and colleagues who derived such joy from this work.

I arrived at the New York Botanical Garden in 1981 to start a one-year postdoctoral fellowship in the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. Through my time in my dads herbarium, I understood the management issues in a small collection built specifically for the research and teaching needs of a contemporary scientist. I was youthfully confident that these skills would transfer well to one of the largest and most active herbaria in the world. It did not take long for me to realize how little I knew.

My first project at the Garden was to organize and index the collections of the William Mitten herbarium. Mitten was a 19th-century English apothecary and self-taught scientist who had obtained bryophyte specimens from essentially all the famous European exploring expeditions. For this project, I handled specimens collected by the likes of Alexander von Humboldt, Joseph Banks, Charles Darwin, William and Joseph Hooker, and many collectors more obscure but equally fascinating. The work was thrilling but frustrating: often these historic specimens lacked adequate documentationa scribble in terrible handwriting might be all that accompanied a historic type specimen, one that has been the basis for a scientific name in use for a hundred years, and often there was no ready source for the information needed to fill in the missing details. From that experience I developed an enduring interest in botanical exploration and historical collections. I loved to read about the adventure but was happiest when I was able to learn more about how collectors approached the less exciting but ultimately more important work of preserving and studying the specimens they collected.

I managed to stay on in a permanent capacity at the Garden after that first year, eventually working my way up through the ranks of herbarium administration. Around the time I became director of the herbarium, I was asked to participate in a workshop, sponsored by the National Science Foundation, about the digitization of herbarium specimens. The facilitator began the workshop by asking the 15 or so participants, most of whom had worked in herbaria for years, to create a timeline of the important dates in the history of herbaria. All of us were stumped. We couldnt agree on any milestones. I was dismayed by yet another example of how ill-informed I was about my own supposed area of expertise but a bit relieved that my colleagues were in the same boat. How odd that even though herbaria are absolutely fundamental to our knowledge of plant and fungal diversity, formal botanical training in the mid- to late 20th century included so little in the way of background about them!

Over the years Ive continued to try to fill the gaps in my herbarium knowledge, and to talk about the importance of herbaria to a variety of audiences. When Timber Press approached me, I was glad for the opportunity of putting some of what I have learned into book form. I hope that the result will be a useful introduction to herbaria for natural history enthusiasts in general but also for colleagues to share with students, new herbarium staff, or maybe even deans or other institutional leaders. I also want to demonstrate, through this book, the wide range of circumstances under which herbarium specimens have been gathered and handled after collection, which accounts for the inconsistency of the data that accompany them. Understanding the journeys of specimens may help users of data derived from herbaria to be aware of both their strengths and limitations.

I also hope that this book will engender an appreciation for institutions that have made the commitment to preserve specimens of plants and fungi in perpetuity. At a time when we seem to be bombarded daily by negative aspects of human nature, herbaria highlight one of our better human impulses: to save things for the future, not just for ourselves but for generations to come. It is true that many times plant and fungal collection has been fueled by imperialism. The impulse to kill these organisms just to store them in cabinets may seem to derive from some base hoarding instinct. However, investing time and resources to care for these irreplaceable representatives of past plant and fungal life and sharing them freely with anyone wanting to study them is both generous and wise. We should celebrate the botanic gardens, museums, universities, and government agencies worldwide that year after year commit their resources to this noble endeavor for the benefit of us all. As much as our modern lives tend to separate us from the rest of earths biodiversity, we cannot exist without it, and these preserved organisms give us information about our world and clues to its future that we cannot learn any other way.

The hardest part of writing this book has been deciding what not to include. In order not to tax the patience of my readers and editors, I could accommodate only a small sample of the stories about the sometimes odd but loveable people who have helped build the worlds herbaria. Also, I could not focus equal attention on herbaria worldwidea realization that saddened me greatly. One of the great joys of my career has been to get to know curators of herbaria all over the world, through my travels and my years as editor of Index Herbariorum ( sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih ), an online registry of and guide to the worlds herbaria. Many of these colleagues, especially those in developing countries, have shown amazing ingenuity and dedication to building and maintaining their herbaria, and are as worthy of attention as anyone included in this book. Because of limitations of space and my own knowledge and foreign language expertise, I have focused most of my attention on collecting and herbaria in Europe, where the tradition originated, and in the United States, although I do include brief histories of herbarium development in four other selected countries. More information about the herbaria mentioned is available at the end of the book. I hope my colleagues in other countries will write the story of their herbaria one day.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Herbarium: The Quest to Preserve & Classify the World’s Plants»

Look at similar books to Herbarium: The Quest to Preserve & Classify the World’s Plants. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Herbarium: The Quest to Preserve & Classify the World’s Plants and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.