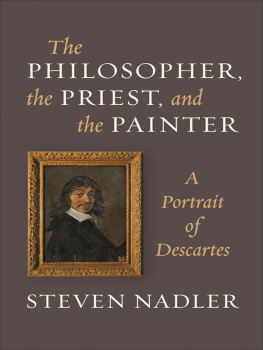

The Philosopher,

the Priest,

and the Painter

FRONTISPIECE. The Netherlands in the seventeenth century

Copyright 2013 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxford-shire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

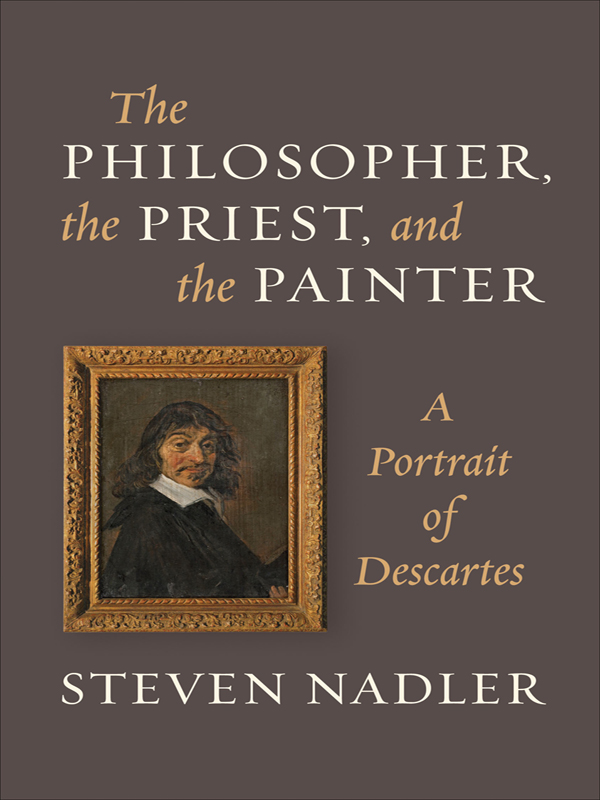

Jacket art: Frans Hals. Ren Descartes (15961650), 1649. SMK Photo. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nadler, Steven M., 1958

The philosopher, the priest, and the painter : a portrait of Descartes / Steven Nadler.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15730-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Descartes, Ren, 15961650. 2. PhilosophersFranceBiography. 3. Philosophy, Modern. 4. EuropeIntellectual life17th century. I. Title.

B1873.N34 2013

194dc23 [B]

2012038718

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon LT Std

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Jane, Rose, and Ben

Contents

Illustrations

COLOR PLATES

Color plates follow page 104.

). Photo: SMK

HALFTONES

Acknowledgments

T his book benefited enormously from the kindness and generosity of many friends, colleagues, and total strangers, all of whom took time away from their own projects to read the entire manuscript or individual chapters, or to respond to my inquiries (which often came via an email out of the blue).

I am, first of all, indebted to several fellow scholars of early modern philosophy (and longtime friends) for their comments, corrections, and suggestions: Jean-Robert Armogathe, Desmond Clarke, Tom Lennon, Han van Ruler, Alison Simmons, Red Watson, and especially Theo Verbeek, who provided copious remarks on earlier drafts and seems to have found every careless error I made (or so I hope).

I also consulted with a number of art historians whose knowledge of seventeenth-century Dutch art and culture was an invaluable resource to this rank amateur: Arthur Wheelock and Henriette de Bruyn Kops (both of the National Gallery, Washington, DC) gave of their time to meet with me and answer some questions, while Seymour Slive helped point me in the right direction on certain matters. Above all, my thanks to Pieter Biesboer (former director of the Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem), who read through the whole manuscript and provided some essential help and necessary emendations. My thanks, as well, to the curators Dominique Thibaut and Jacques Foucart (both of the Louvre) and Eva de la Fuente Pedersen (Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen), who responded to my inquiries about their collections. I also want to thank my friends and colleagues in the Department of Art History here at the University of WisconsinMadison, who invited me to present some of this material at a departmental colloquium and who sat patiently while an interloper struggled to act and sound like an art historian. I especially appreciate the useful advice on the book (and lessons on how to look at paintings) that I received from Suzy Buenger and Gene Philips.

In addition, I am very grateful to a number of other colleagues (at Wisconsin and elsewhere), scholars, and friends for their help: Susan Bielstein, Wim Cerutti, Rob Howell, Ben Kleiber, Shannon Kleiber, Henriette Reerink, Russ Shafer-Landau, Larry Shapiro, and Henk van Nierop.

Tanya Buckingham and her colleagues in the Cartography Lab at the University of Wisconsin did a terrific job (and showed great patience with me) on the map that they prepared of the United Provinces in the seventeenth century.

Finally, my thanks to Rob Tempio, my editor at Princeton University Press, for having faith in what is, admittedly, a rather eccentric project (and who now owes me lunch at Katzs); to Debbie Tegarden, also at the press, for all her help along the way; and to Jodi Beder for outstanding copyediting that resulted in a greatly improved manuscript.

Research on this project benefited from funds provided by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) Professorship, which I was fortunate to have been awarded; and from a semesters leave at the Institute for Research in the Humanities supported by the College of Letters and Science, University of WisconsinMadison.

This book is dedicated, with great love, to my wife Jane, and our children Rose and Ben.

The Philosopher,

the Priest,

and the Painter

CHAPTER 1

Prologue: A Tale of Two Paintings

O n the third floor of the Richelieu Wing of the Louvre in Paris is a gallery devoted to Holland, First Half of the 17th Century. Room 27 is not one of the museums more traveled venues. Visitors, if they stop to see the artworks in the room, do not stay long. There are none of the Louvres world-famous masterpieces here: no Mona Lisa, Winged Victory, or Venus de Milo. There are not even any of its better known and often reproduced paintings; Gericaults The Raft of the Medusa and Delacroixs Liberty Leading the People are in the Sully Wing, while Caravaggios Fortune Teller is in the Denon Wing. Although Richelieu Salle 27 is devoted to seventeenth-century Dutch art, there are no Rembrandts or Vermeers or Ruisdael landscapes on its walls. Not even the most ardent fan of Dutch Golden Age art will find much here that is exciting.

Most of the artists represented in this room are second tier at best. While some of the works are finely executed and charming in subject matter, many of the painters names will probably be familiar only to specialists. There is a Landscape with St. John Preaching by Claes Dirckszoon van der Heck, Jesus with Mary and Martha by Hendrik van Steenwyck, a Basket of Flowers by Balthazar van der Ast, an ice-skating scene by Adam van Breen, and a festive gathering by Dirck Hals. The gallery has a number of history paintings and ancient landscapes by Cornelis van Poelenburgh, as well as Jacob Pynass The Good Samaritan. Visitors who know Dutch history will be drawn to Michiel van Mierevelds portrait of Johan Oldenbarneveldt, the liberal leader of the province of Holland until he was accused of treason by his political enemies and beheaded in 1618.

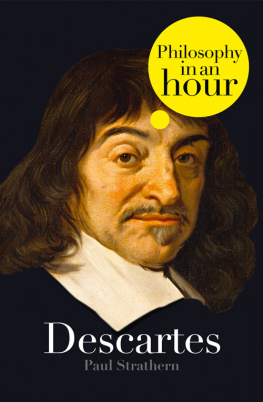

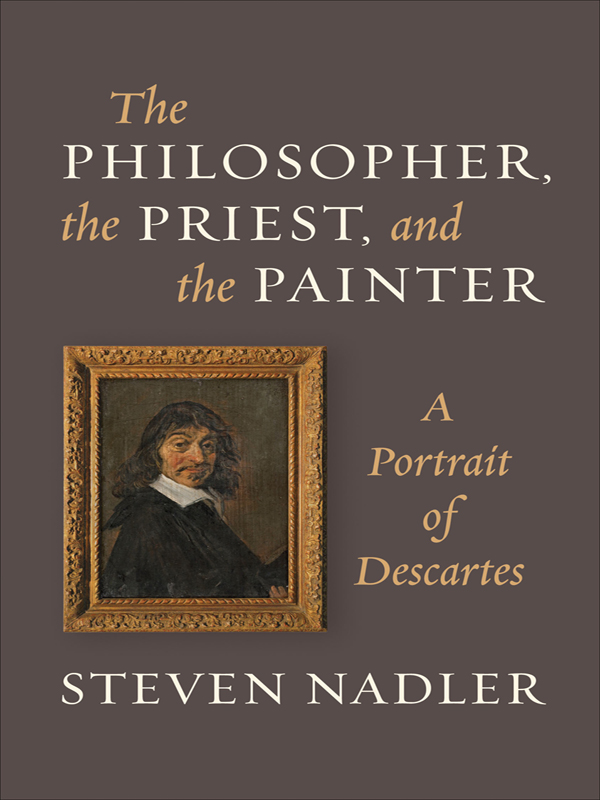

Room 27 is also home to a portrait that, to some viewers, will seem very familiar. On the west wall hangs a canvas in a gilded frame depicting a man of middle age. Attired in a large, starched white collar folded over the neckline of a black coat, he looks like a typical Dutch burgher. He has dark shoulder-length hair, a moustache with a patch of beard just under his lower lip, a long aquiline nose, and heavy-lidded eyes. In his right hand he is holding a hat, as if he has just removed it. On his face is a quizzical expression as he stares outward to meet the viewers gaze. It is the most famous image of the presumed sitter, who is identified by the label as Ren Descartes, the great seventeenth-century French philosopher, mathematician, and scientist (color plate 9). The painting, once owned by the Duke of Orlans and acquired by Louis XVI in 1785, was long believed to be by Frans Hals, the seventeenth-century Dutch master. While many outdated and less than authoritative sources continue to say that the life-size portrait is by Hals, the Louvreon the basis of the works painterly qualities and in the light of dominant scholarly opinionhas downgraded it. It is now identified as a

Next page