Dudley Cook - The Ax Book

Here you can read online Dudley Cook - The Ax Book full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Stackpole Books, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Ax Book

- Author:

- Publisher:Stackpole Books

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Ax Book: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Ax Book" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Ax Book — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Ax Book" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Conway, Steve. Timber Cutting Practices. 2d ed. San Francisco: Miller Freeman, 1973.

Curtis, Will and Jane. Artistry in Iron. Ashville, Me.: Cobblesmith, 1974.

Defenbaugh, James Elliott. History of the Lumber Industry of North America. Vol. II. Chicago: The American Lumberman, 1907.

Furnas, J. C. A Social History of the United States, 15871914. New York: Putnam, 1969.

Johnson, Allen J., ed., George H., Auth, assoc. ed. Fuels and Combustion Handbook. 1st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1951.

Kauffman, Henry J. American Axes. Brattleboro, Vt.: Stephen Greene Press, 1972.

Ketchum, Richard M. The Secret Life of the Forest. New York: American Heritage, 1970.

Mason, Bernard S. Woodcraft. New York: Barnes, 1939.

Mercer, Henry D. Ancient Carpenters Tools. Doylestown, Pa.: Bucks County Historical Society, 1960.

Morison, Samuel Eliot. The European Discovery of America: The Northern Voyages. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

Orton, Vrest. The Forgotten Art of Building a Good Fireplace. Dublin, N.H.: Yankee, 1969.

Panshin, A. J., and Carl de Zeeuw. Textbook of Wood Technology. 3d ed. Vol. I. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1970.

Sandvik Steel Works Co., Ltd. Sandvik Forestry Saws. Stockholm, Sweden, 1957.

Simonds Mfg. Co. Simonds Cross-Cut Saw Plan. Fitchburg, Mass., 1915.

Sloane, Eric. The Seasons of America Past. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1958.

Sloane, Eric. A Reverence for Wood. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1965.

Sloane, Eric. The Second Barrel. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1969.

Smith, David C. History of Lumbering in Maine, 18611900. Orono, Me.: University of Maine Press, 1972.

Snow & Nealley Company. Catalog #66. Bangor, Me., 1 November 1948.

Thoreau, Henry David. The Maine Woods. New York: Bramhall House, 1950.

Tocqueville, Alexis de. Democracy in America. Translated by George Lawrence. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday Anchor, 1969.

Wackerman, A. E., W. D. Hagenstein, and A. S. Mitchell. Harvesting Timber Crops. 2d ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966.

DONT SNEER AT THE AX. ITS GENEALOGY MAY BE BETTER THAN YOUR OWN. THERE is no need to be afraid of it either. You can easily learn to use it. And as things seem to be shaping up, perhaps you should learn.

For uncounted generations, the ax was mans best tool. Early man did just about everything with it. He dug tasty roots, chopped fuel and building materials. He caught running food and took care of troublesome neighbors, the latter two often simultaneously. Our more recent forebears cleared land, built log cabins, and kept warm by means of their axes. In our climate, to live in the woods, a man had to have an ax.

It is true that we do not have quite the same manner of living today. But before feeling too superior, check what you have been paying lately to keep warm. If your winter fuel bills seem to have cancerous growth of some sort, maybe relearning the ax could be profitable to you. It can certainly be enjoyable.

The modern tree-felling ax is an efficient instrument perfected during a long history. Mans first tool was undoubtedly a club or hand-held stone. But somewhere in the past millennia, some of our cleverer ancestors put a club and a stone together to make an ax, and a whole new era began. Men could hit harder and cut deeper.

When metals were discovered, metal striking tools would have been among the first applications. The resemblance between the later, more skillfully formed stone axes and the earliest known bronze specimens is remarkable. Bronze axes probably more than 3,500 years old have been

unearthed from ancient Ur in what is now Iraq. A double-bitted ax found in Crete dates back to 20001700 B.C.

That axes became weapons was only natural evolution. As well as for chopping up roots, an ax was useful for chopping down enemies. History can be viewed as a compilation of peoples who repeatedly resorted to this sort of activity. Much early and classical artwork depicting warriors shows axes carried as weapons. The weapons themselves were sometimes bits of art. As with swords, the battle-axes of chieftains were often chased in silver and gold. As armies grew, there were whole formations of axmen. Even development of the many forms of the sword did not entirely supersede the ax. The ill-fated Harold II, king of Saxon England, apparently wielded a mighty two-handed ax. But at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, Harold lost. England fell to William the Conqueror and the Normans.

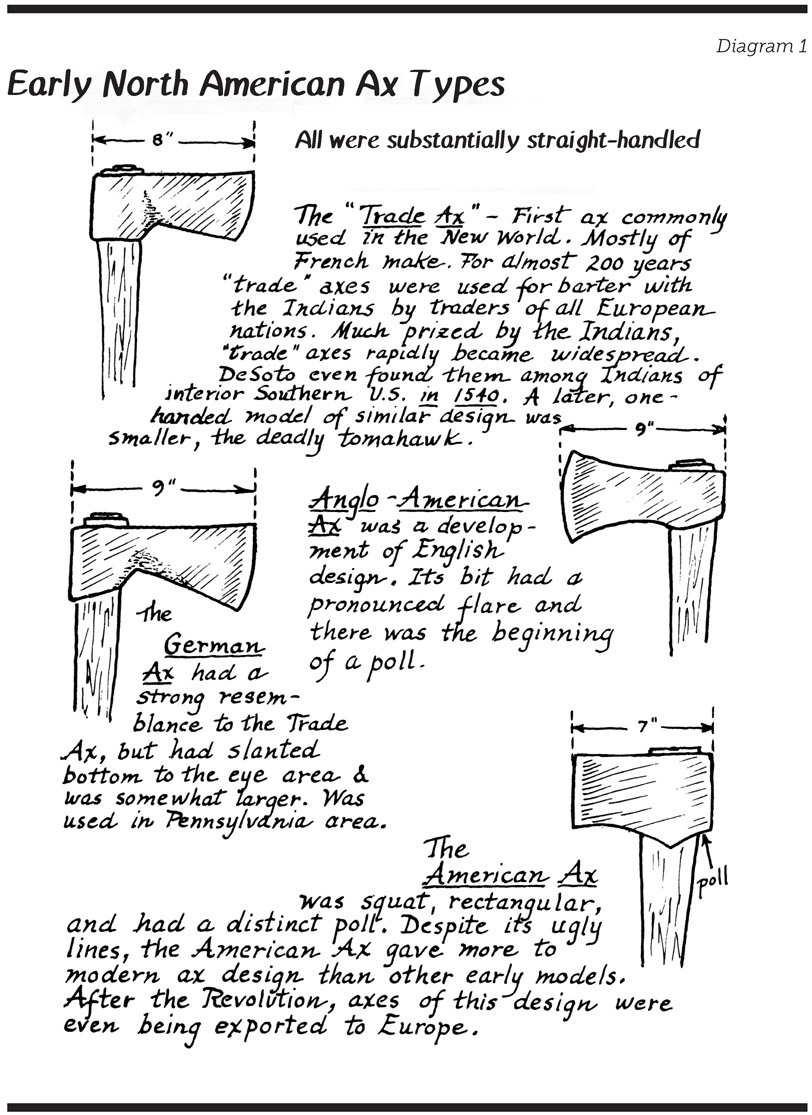

With the settlement of America, the ax emerged as the prime tool of necessity, even before a gun. In a land of forests, the trees had to be cleared so that crops could grow in the sunlight of open fields. So the first Americans made it their business to destroy as many trees as possible. What they accomplished is as amazing as, from our viewpoint today, it is dismaying. But for families that had to bare the soil to plant seed, it was Root, hog, or die! Their work in eliminating whole regions of forest, leaf, limb, trunk, and root, surpasses any effort that a labor union could conceivably have a nightmare about today.

Indispensable as the ax was, it alone was insufficient means to accomplish that gargantuan land-clearing task. Usually the great trees were deadened with the ax, which gouged the life-giving sapwood in a girdle about the trunk. Left to die so as to burn better, or just to rot eventually, trees would stand for years as ugly monuments to the energy of man. Meanwhile, with the fallen leaves or needles no longer blocking the sun, crops could be sown among the stumps and the branching towers of wood.

That depressing spectacle was particularly noticed by new travelers through American frontier areas. The desolation surpassed anything within their experience. As late as 1840, Alexis de Tocqueville, a French observer, described such a scene: All the trees seemed to have been suddenly struck dead. In full summer, their withered branches seemed the image of winter. But for the settlers who lived there, this stage was necessary to make the land productive. For largely, food came from field crops, not from the forest.

Nor was the work of the axman finished with killing the trees, even if they were to be soon burned. For you could not plow through roots. The stumps had to be laboriously split apart if possible, then grubbed out or back-breakingly pulled out down to the rootlets. Stumps moved easier if they rotted for a few years, but however done, it was a stupendous task. All across the eastern half of North America, this process was repeated wherever forest gave way to farms. In any area, the entire cycle took years to complete. Only among the painstaking Pennsylvania Dutch was it commonplace to convert a plot of ground from forest to root-free cropland within one year.

To the early settlers, shelter was also vital. In the bitter winters, shelter was often an even more immediate need than food. Some of the first shelter arrangements were only caves or brush leantos. But with the plentiful trees, houses built from criss-crossed logs notched together at the corners soon became common merely because the materials were available everywhere for the cutting. The ax was indispensable. To fell enough trees to make a cabin for his family, a man had to have an ax. Contemporary drawings and accounts of the early cabins describe a feature common to virtually all of them, the tapered and hacked-off butts of each log. These were cut with axes. There was no other way to procure the abundant trees for either fuel or construction.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Ax Book»

Look at similar books to The Ax Book. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Ax Book and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.