Table of Contents

FOREWORD

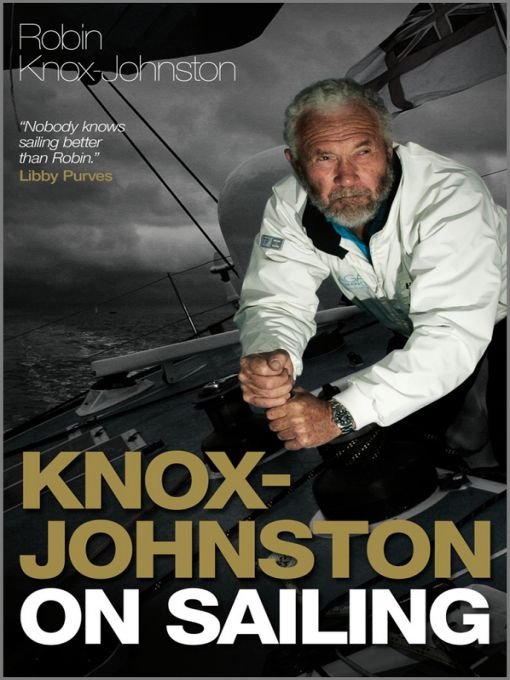

Although, in theory, a magazine editor has a free hand over the content of their magazine, in practice major changes to the editorial mix are very difficult, though not impossible, to implement. In practice the only time the editor is free to perform major surgery is when they first take over. Such was my situation when I took over a faltering Yachting World in late 1992 and in I waded with a sharp axe. In fact so sharp was that axe that by the time I planned out my first issue as Editor there were only two out of several regular features left in the mix. One of those was Robin Knox-Johnstons regular column which continues today some 18 years later. In this Robin brings an uncommon dash of seamanship and common sense that keeps Yachting World bolted firmly to the floor as a foil to the hi-tech world of racing, the Americas Cup and the latest technical wizardry.

Dont get me wrong. Robin, or Sir Robin as he is now, is far from being a dyed-in-the-wool traditionalist. His knowledge and writing spans everything from current ideas to the traditional as is well illustrated by the fact that he still sails his decidedly low-tech gaff ketch Suhaili despite racing the ultra high-tech Open 60 Grey Power in the last Velux 5 Oceans round the world solo race. What his column recognises and promotes is that there are many aspects of sailing and seagoing that are every bit as relevant today as they would have been a century ago. The way we go to sea might change but the sea, and wind, remain the same.

What makes Robin so different from many other yachtsmen who have achieved great things is that having, in 1969, become the first person to sail solo, non-stop round the world, he continued to be very active in the sport with other circumnavigations and notable passages to his credit all without self-aggrandisement. Not only that, he remains even today, Britains best-known sailor and promoter of sailing in its broadest sense. Which is why, in 1992, that sharp axe passed over his column. And lets hope he stays on as a Yachting World columnist for many years to come.

Andrew Bray

June 2010

PREFACE

The world of yachting has changed massively since I set sail on Suhaili, my 32ft ketch, to sail around the world. That was in 1968 and the voyage took 312 days at an average speed of just over four knots. As I write, the current solo record stands at just 57 days. I have been lucky enough to be involved with this transformation from tortoise to hare, competing on giant multihulls, round the buoys in the Admirals Cup and on Open 60 monohulls though Suhaili has stayed with me throughout.

Technology has transformed sailing. Composite materials, weather routing, self-steering systems and satellites which have given us instant communications, weather information and global positioning have allowed yachtsmen to sail faster and faster and the records will continue to fall. There is, however, more to sailing than battling the oceans and the record books. The thrill of exploration, whether of Greenlands frozen shores or of a quiet local creek, is something that every sailor feels, and it continues to draw me to the sea and provide a wide range of subjects for my Yachting World column.

Over the past 18 years writing for Yachting World each month has been a huge pleasure, and one I still enjoy, although sometimes the deadlines have crept up on me! I have been given a free rein, allowing me to change my focus from the latest race or rescue to more general reflections on sailing and seamanship. This selection reflects that diversity. I hope there is something here for everyone to enjoy.

Robin Knox-Johnston

June 2010

PART ONE

Going Places

THE DEVIL YOU KNOW

Every sailor thinks his own part of the world has the nastiest stretch of water. Robin thinks the Thames Estuary takes a lot of beating ...

Have you noticed that wherever you sail in the world, with very few exceptions, the local yachtsmen will always tell you that they have the most dangerous sailing conditions anywhere on Earth?

My first introduction to this peculiarity came when sailing back from India a few decades ago. Before we left Bombay, we were warned about the dangers of the Indian Ocean. We miraculously survived the crossing to Muscat, to be told there that the coastline down to Aden was far more difficult. In Mombasa, the treacherous crossing of all these dangers was as nothing compared with the East African coast, and so on.

Wherever we arrived, people dismissed what we had been through, except, of course, the last day or two as we approached their area where we had obviously been lucky.

We actually did believe them in East London when they told us about the Cape of Good Hope, but the Capetonians were much more in awe of the Skeleton Coast.

The people of Brest will tell you about the Chenal du Four, Australians about the Tasman, Hong Kong sailors about the China Sea.

Personally, I have always felt that the Thames Estuary takes some beating. An easterly gale on an ebb tide from Sea Reach onwards creates conditions which no one in their right mind would wish to experience in a small yacht.

However, I assumed that this was just my own prejudice until French sailor, Titouan Lamazou, told me that he was concerned at the possibility of bringing his 140ft sloop, drawing 6.5m, to London in 1993. He, like many other Frenchmen, found the estuary alarming, not because of the wind and waves, but on account of the banks and tides.

I am sympathetic. The Thames is not easy and the unwary can swiftly find themselves aground some distance from their DR position especially now the number of navigation marks has been reduced. Even in moderate visibility I consider the Thames to be the complete justification for investing in GPS.

TOGETHER ACROSS THE POND

Crossing the Atlantic is still a major achievement, no matter how many others have already done it. The Atlantic Rally for Cruisers is a good way for amateur sailors to cross in company.

If John of Gaunts grandsons had been interchanged so that King Henry V of England had been Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal and vice versa, then it is just possible that England might have started exploring by sea earlier: any one of the Canary Islands, Madeira or the Azores might have been English, not Spanish or Portuguese.

Of course, we would not have had Agincourt, but as compensation there would have been a nice warm Atlantic island in the Northern Hemisphere, selling beer instead of wine. Whether this is a great loss is a moot point; a major attraction of the islands, in addition to the mild maritime climates, of course, is their Iberian charm.

Of the three, the Canary Islands might be said to have staked an early claim as the jumping off point for an Atlantic crossing, since Columbus sailed from Gomera, one of the group.

There was practical logic in this. The Azores are on the edge of the westerlies, usually in their grip during winter when they can reach storm force (I experienced 98 knots in December 1989 while moored in Praia da Vitoria), so a voyage west was likely to be against the wind in the winter and beset by calms in the summer.

In the days before proper salting of meat and no means of keeping water sweet, voyages were severely restricted to the length of time the available stores lasted.