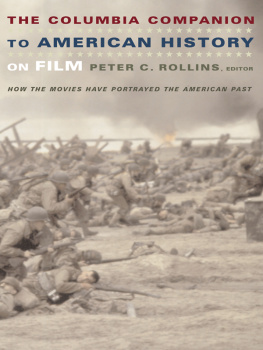

THE COLUMBIA COMPANION TO

AMERICAN HISTORY ON FILM

Edited byPETER C. ROLLINS

THE COLUMBIA COMPANION TO

AMERICAN HISTORY ON FILM

How the Movies Have Portrayed the American Past

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESSNew York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2003 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-50839-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The Columbia companion to American history on film : How the movies have portrayed the American past / edited by Peter C. Rollins

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-231-11222-X (cloth : alk. paper)

1. United StatesIn motion pictures. 2. United StatesHistoryMiscellanea. I. Rollins, Peter C. II. Title.

PN1995.9.U64 C65 2004

791.43/658 21

2003053086

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

To John E. OConnor and Martin A. Jackson,

cofounders of Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television History

(www.filmandhistory.org)

CONTENTS

Susan Rollins, Leslie Fife, and Deborah Carmichael helped prepare materials for this book, and they have my great thanks. Throughout the project, James Warren of Columbia University Press was a demanding and hard-working colleague. Gregory McNamee was a joy to work with and enhanced both the consistency and insight of the manuscript. William F. Waters of Films for the Humanities provided authors with relevant documentaries from its collection; both he and Films for the Humanities deserve an emphatic note of thanks for making these resources available (www.films.com). I thank, too, Oklahoma State University for honoring my work by appointing me Regents Professor. A long series of department heads have promoted my efforts, among them Jack Crane, Leonard Leff, Jeffrey Walker, Edward Walkiewicz, and Carol Moder. I am most grateful for their support and faith. Finally, the staff of Film & History (www.filmandhistory.org) was ever generous with suggestions, help with documentation and filing, and production of the final manuscript.

Film and television define our perceptions of our time and of historical experience. In 1973, John Harrington warned about the power of visual media to shape the contemporary sensibility, estimating that by the time a person is fourteen, he will witness 18,000 murders on the screen. He will also see 350,000 commercials. By the time he is eighteen, he will stockpile nearly 17,000 hours of viewing experience and will watch at least twenty movies for every book he reads. Eventually, the viewing experience will absorb ten years of his life (v). Nearly thirty years later, psychologists Robert Kubey and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi described contemporary viewing as a form of addiction: The amount of time people spend watching television is astonishing. On average, individuals in the industrial world devote three hours a day to the pursuitfully half of their leisure time, and more than on any single activity save work and sleep. At this rate, someone who lives to seventy-five would spend nine years in front of the tube (76).

Through video rentals and reruns, film and television recycle themselves to consummate their impact on popular memory. All citizens need to ponder the implications of such statistics, but historians should be particularly concerned about this phenomenon, for what millions see on theater and television screens defines what is called popular memory, the informalalbeit generally acceptedview of the past. Indeed, visual media define history for many Americans. The Columbia Companion to American History on Film, a collection of essays that explore how major eras, institutions, peoples, wars, leaders, social groups, and myths of our national culture have been portrayed on film, offers readers and researchers an unparalleled resource on a vital source of historical interpretation and reflection.

Many scholars welcome the plethora of films and television programs that depict our history. They see film as a way of introducing and dramatizing the events, ideas, and forces that have shaped history and identity. But the use of films as sources of historical interpretation is not without problems or detractors. Take, for example, the case of the HBO feature film A Bright Shining Lie (1998), which purported to adapt a Pulitzer Prizewinning book to the screen. In the process so many changes were made that author Neil Sheehan and a major character, Daniel Ellsberg, threatened to sue the filmmakers for misrepresentation because the complex and ambiguous story of Americas role in Vietnam had been reduced to a cinematic diatribe against American intervention. (For Ellsbergs trenchant discussion of the subject, consult the Film & History web site, www.filmandhistory.org.) Yet very few viewers are worried about poetic license, inventions, and deletions by filmmakers. Most are more interested in good stories about the past than accuracy of analysis. As filmmakers will tell you, they constitute an audience that simply wants to be entertained.

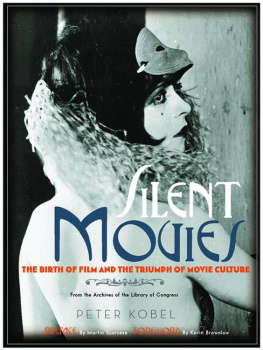

Since their inception, motion pictures and television have exerted a profound impact on our understanding of the past. As historical sources they can be very useful and revealing, but they must be read with sensitivity, care, and discrimination. During the silent era, directors such as D. W. Griffith helped to define the meaning of westward expansion and the significance of the Civil War. Silent-era director James Cruze contributed his vision of an Anglo-Saxon West in his adaptation of Emerson Houghs The Covered Wagon (1923). These ambitious early films spoke volumes about American values in an era anxious about the impact of immigration, and The Covered Wagon in particular helped smooth the way for the Immigration Restriction Act of 1928. Throughout the so-called Studio Era (193048), leading producers and moguls took pride in underwriting historical films as part of the quality work of their corporations; David O. Selznicks Gone with the Wind (1939) is perhaps the most famous example of a lavish film made to interpret American history to a large audience, an immensely popular project about which film scholars have been quarreling ever since. Such films were made as a gesture toward defining our national past, and some were made without concern for profit. Whether aimed at making money or not, they taught memorable lessons.

In recent decades, Oliver Stone has pilloried the American system in films such as Platoon (1986) and Wall Street (1987). Some critics consider him a history teacher, and in 1997, assuming that role, he spoke to the American Historical Association in a packed hall of more than 1,200 academics. He did not win over many of his critics. Historians deplore Stones mlange of fact and speculation. As George Will, a noted columnist and former professor of politics, has observed rancorously, Stone falsifies so much that he may be an intellectual sociopath, indifferent to the truth. In the feature film

CONTENTS

CONTENTS